by Tom Van Zoeren, Port Oneida historian

Ed. Note: The following is adapted from the “Images & Recollections from Port Oneida” series of books produced by Tom Van Zoeren in partnership with the Friends of Sleeping Bear Dunes. The books are based on oral histories and photos collected from natives of the farming community, which is now preserved as a Rural Historic District within Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore. The books are available at area bookstores and through VZOralHistory.com.

The early beginnings of the Werner family in America are now misty—but around 1854 Frederick and Margretha Werner left their crowded, oppressive homeland of Hanover (now a part of Germany) and sailed to the New World with several small children. Arriving in New York, the Werners purchased 202 acres of Port Oneida land, sight-unseen, for 75 cents/acre. They then sailed up the Great Lakes to South Manitou Island to spend the winter. In the spring the young family crossed the Manitou Passage, climbed the steep shoreline bluff, and surveyed their piece of primeval forest. The land was rolling, and included a hilltop that looked over the surrounding lands and waters; but it also included some level ground that promised good crops. The Werners began the task of establishing a home in the wilderness, a half-mile down the coast from the only other white settlers in the area, Margretha’s brother Carsten Burfiend and his family.

Frederick built a small log cabin in a sheltered spot near the bluff above the lake. He then began clearing the virgin forest for a farm. The details of their lives can only be imagined; but it’s told that the family lost three children to pneumonia during the first years in Port Oneida. During following years Margretha bore more children to total 14. Five did not survive childhood, and rest in the family graveyard overlooking the lake.

Among the trials of life on the Great Lakes frontier, early settlers faced raids by the renegade Mormon cult of King James Jesse Strang. Jack Barratt, great-grandson of Margretha’s brother Carsten, told this tale: “The Mormons—when they were on the rampage—they arrived one day at Port Oneida; and my great-grandfather was gone, and only my great-grandmother and the children were home. She took all of the kids upstairs, and there was a trapdoor—I remember this trapdoor at the head of the stairs that came down over the stairway—and she piled all the dressers and the beds and everything she could get on the door so they couldn’t come upstairs. But they took food out of the kitchen and everything they wanted, and before they left, they slashed all the fishing nets that were out on the drying reels, and they took an ax and they put holes in the bottom of the boat.”

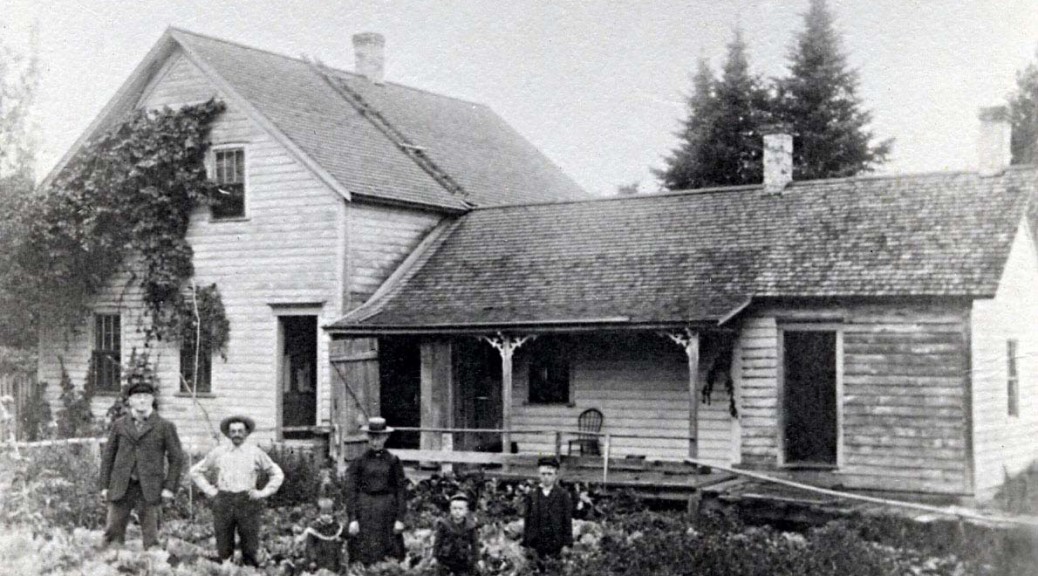

Of course, a wilderness pioneer has little means for precisely determining property lines, and after 15 years building a farmstead, the Werners were informed by their neighbor to the north, Thomas Kelderhouse, that their home was on the wrong side of the line. The Werners had to disassemble their hard-built home and farm, and relocate 1/4 mile southwest to the location seen here. There are no foundation remains left to mark the original home site. Great-grandson Charlie Miller believes it was constructed on a base of logs.

By the time of this earliest family photo, a half-century after arriving in Port Oneida, the Werners’ daughter Margaret had married, and her husband, John Miller, had taken over farm operations. Here they pose in front of their home; L-R, they are pioneer Frederick Werner; his son-in-law John Miller; daughter (Mr. Miller’s wife) Margaret; the Millers’ daughter Annie; their son Charlie; and John Miller’s son by a previous marriage, John. Pioneer Margretha had died five years earlier.

By the time of this earliest family photo, a half-century after arriving in Port Oneida, the Werners’ daughter Margaret had married, and her husband, John Miller, had taken over farm operations. Here they pose in front of their home; L-R, they are pioneer Frederick Werner; his son-in-law John Miller; daughter (Mr. Miller’s wife) Margaret; the Millers’ daughter Annie; their son Charlie; and John Miller’s son by a previous marriage, John. Pioneer Margretha had died five years earlier.Like most Port Oneida men of his time, John Miller spent his winters working in the logging woods to earn precious cash. An accident there left him with a wooden leg on which to work his farm. Adding to the family’s difficulties, his wife suffered from mental illness. Grandson Charlie Miller recalls, “She liked to bite my sister’s arm. She got put away for a while. Twice she got put away at the state place in Traverse.”

The original log cabin on this site was eventually added onto and covered with clapboard siding, but remained within the walls of the one-story portion of the house seen here. The old house is gone now, but Charlie believes that the tree just peeking above the roof to the left of the larger spruces is the huge cedar that can still be seen south of the end of Miller Road, along the way to the old barn.

Van Zoeren is a retired Sleeping Bear Dunes Park Ranger, who now works to preserve Port Oneida history. All of the oral history interviews, their transcripts, and related photos that have been collected have been donated to the public domain and are available in digital form at the Glen Lake Library (Empire) or from Tom. He welcomes your questions, comments, and further Port Oneida information (via email at VZOralHistory.com).