(This document is provided courtesy of the Traverse Area Historical Society, 322 Sixth Street, Traverse City, MI 49684)

EAST JORDAN, MICHIGAN TO YORK STATE

INTERESTING AUTOMOBILE TRIP DESCRIBED by Miss JENNIE WATERMAN

In Three Letters published in the CHARLEVOIX COUNTY HERALD

A Weekly Newspaper in East Jordan, Michigan

Mr. George Lisk, Editor and Owner

Detroit, Michigan

August 7th 1913

Dear friends:

There is always a kink in a real trip to start out on, don’t you think? We wanted good omens, though, so we refused to go back after our lunch when we discovered it was missing, a couple miles out of town. We left Main Street at 6:43 and made Eastport at eight o’clock. About twenty more miles brought us to a field of five-inch corn and a corresponding backwardness in other crops. The hypothesis that last year’s crops had been as poor is all that we could find to account for the straight-tailedness of the pigs in the next fields.

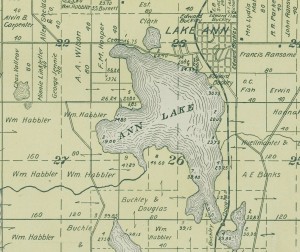

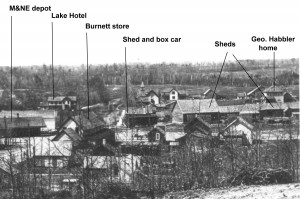

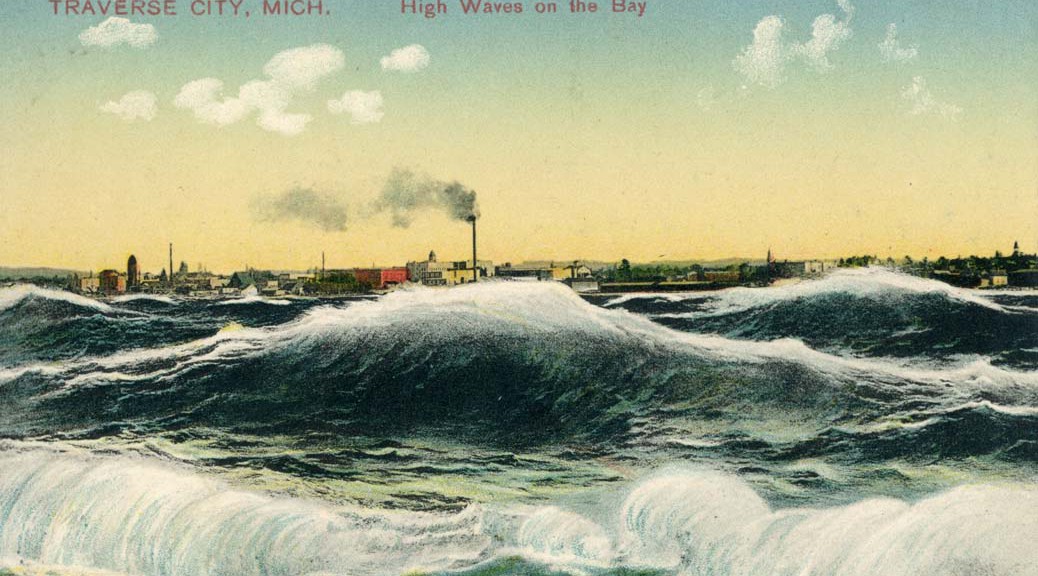

We found teams working on the roads but had no trouble before reaching Traverse City at 9:55, coming into the town along that beautiful stretch of road right beside the Bay which we had seen before only from train windows, and passing the high board fence about the large Fair Grounds. In Traverse City, Father’s cousin, Edwin P. Waterman, surveyor for Grand Traverse County, made us a plat of the roads we were to follow as far as Manton. We passed through a storm area just below Buckley. Buckwheat fields are numerous and flourishing from Buckley and east of Big Rapids.

We made Cadillac, 106 miles from home, at 2:50. There we separated, Mother and Father going on with Gertrude Bretz to stay the night at her parents’ far home near Evart, and I taking the train for Big Rapids, where I would sign out at Ferris Institute and Eva and I would be packed ready for the next day’s start. The car made 141 miles that Tuesday for the first day of our trip.

Wednesday morning we left Big Rapids with the entire party of five and paraphernalia at 9:35 a.m. The things along the road of incidental interest were a young quail, and later a real sauger that had shed its rattles, this being the season for that. Cobble stone houses appeared often and we think they are fine. Certainly they had some artistic and comfortable porches. An unusual number of fine big barns were either just finished or in process of construction, and we had several glimpses of wind-stackers in action.

At Mt. Pleasant we discovered that the valve had been broken off, letting the water out of the cooler, and used three pails of water in cooling the machine down. Through Gratiot County we saw beautiful level fields and really got to missing our native hills before we struck some slight grades in Lapeer County. Farming looked pretty prosperous through there, with oat crops especially fine. At Shepard they were repairing a bridge, so with fear hidden and smiles showing—we forded a river! It really was an interesting experience, water coming not quite over the tool-box on the running board. Just about here we passed groups of splendid farm buildings.

We saw a storm ahead of us at 4:30 but it was traveling the same direction we were and we did not overtake any of it but the puddles. This was along the thirty miles of absolutely straight road between St. Louis and Saginaw which we made in an hour and a quarter. The farms and the buildings looked poorer from St. Louis on. We had made 170 miles for the day when we stopped for the night at Mayville.

Our third day started out beautifully. Everybody smiled. A farmer with a wagon load of milk cans assured us we were good looking but his horse was afraid of us just the same! Barley fields were fine through to Brown City. We found silos quite numerous and they commonly have an octagonal roof which I have never seen up north.

We found a rather faded Stroebel Bros. Hardware sign. It did not say, but we figured it out to be 328 miles 32 rods from home. Query—does advertising pay? A large pig was out in the road as we passed the sign and when we tooted he immediately advanced to meet us and waited in the middle of the road until we stopped the car before deciding in favor of the clover on the right hand side of the road.

We found the clay roads of Lapeer County bad after the storm. Whenever the roads are bad, we think we must be off the route and stop for instructions. Conferring with one knight of the pipe—said pipe of unestimable strength—and were recommended in all sincerity to “keep right on the telegraph poles and we couldn’t miss it.” Mother, of course, held the King’s Blue Book and read off to Father the directions as to “half a mile to a stone-heap on the right, then one mile to the small church on the left before turning east” but even such help had weak points.

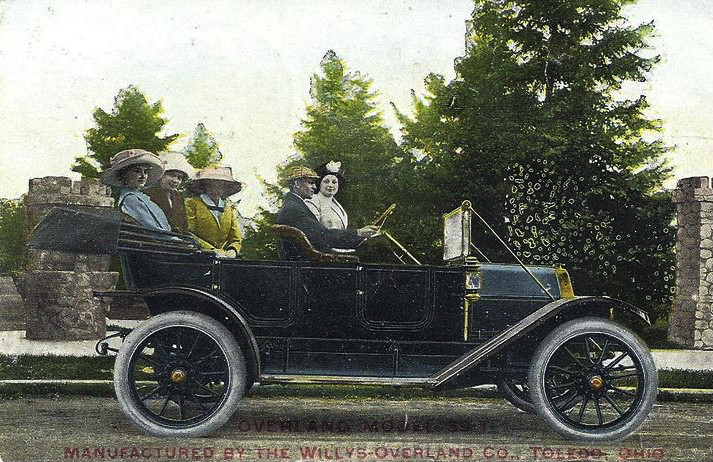

In following local instructions we rode over a clay bump and broke the rear right hand spring on the Overland. This was near Yale, 38 miles from Port Huron, where we had intended to cross into Canada. Father found that we could not get a new spring in Port Huron so trailed cautiously on into Detroit shortly after 7:00 p.m. He has taken the train to the Overland Car Works in Toledo to bring back the needed spring, and we hope to leave dear old Michigan by noon tomorrow!

A punctured tire happened between Mt. Clemens and Detroit. Gertrude Bretz and I had taken a train from Mt. Clemens to Detroit to lighten the load and so I still have my first tire-experience coming. I suppose it is safe to say it is coming.

This is rather a bad place to leave the narrative but there’s a better day coming. And then it is rather exciting, “projeckin’” until you hear next time. Being an editor, you realize the psychological value of that!

Sincerely,

Jennie Waterman

________________________________________________

Stafford, New York

August 15, 1913

Dear friend:

While the chauffer [sic] is riding around the country with the sheriff (who happens to be in the family) of Genessee [sic] County, we “women folks” are set down on a lovely York State farm long enough to breathe twice. This particular visit is to last twenty-four hours. But perhaps you want to know how we got out of Detroit.

When Father came back from Toledo Friday with the new spring the garage people had found a broken casting—which might have been made in an hour by Maplass Foundry—but the original article was preferred and another twenty-four hour wait, it seemed. At least the garage people thought so. Mother and we three girls spent most of Friday on Belle Isle and the pleasure boats. Except for the delay our time and experience in Detroit were interesting. The all-negro orchestra on the boat Promise had one member with red hair and blue eyes, but the music was wonderful. But we liked to choose our own ways so pretended to be very bored.

Customs officers are jolly people. Doubt if they could survive long otherwise. Getting from the garage to the ferry dock Father got in a hurry and took the turn onto Woodward a few feet nearer the left than the right (both meanings) and a blue-coat inquired where we were from. We spread the charge as thin as we could by saying “Northern Michigan” so East Jordanites need not feel diffident about visiting Detroit.

The customs officers asked a few questions, gave advice, mysterious papers, and a reduced toll “because of the ladies,” then waved us majestically onto the Excelsior Ferry. The crossing took five minutes.

Canadian red tape must be stickier than ours, it took so long to unwind, and was it ever hot in that narrow cobbled street between tall brick buildings where we had to wait! It cost us $14.00 to go through Canada, $4.00 for the licence and $10.00 for bonds–$5.00 of which we will get back when we are home again and Canada is satisfied we did not just drive over to sell our car! At 5:20 p.m. Saturday we were ready to leave Windsor. There was some trouble getting onto the right street to “turn this way, then that way, then this way, then that way, until you hit the telephone poles.” Just out of Walkerville we passed several large fields of tobacco plants and these occurred all along our route through Canada.

We were so anxious to make up for lost time that we drove eighty-one miles before 11:45 when we stopped in Blenheim for the night, pounding on the door and bringing the proprietor out onto a tiny balcony above the door in his nightcap before he came down to unlock and let us in.

Next morning we found the dining room, and our good breakfast, decidedly English. Where in the U.S.A. we have mirrors and out glass and flowers, they had copper platters, queer spears and arms. Three great tusks of elephants decorated the sideboard. It was raining when we left Blenheim and rained by spells until late afternoon. The worst of the storm was east and south of Blenheim in the country through which we had to go. Corn and grain were laid flat or standing in great lakes of water. The clay roads were really dangerous. The car slewed dreadfully even with the chains on. At Ridgetown we were warned of a formidable hill which we might not be able to make. But because we are from Michigan, Canada has yet to show us any hilly roads.

At London we stopped for dinner. Since it was Sunday everything was closed tight, with the exception of one large Chinese restaurant. There we were smilingly offered “Sli” tomatoes, green peas, Flench flied potato, yah!” We ordered and then Mother led us determinedly back to the kitchen to wash our hands. Such a kitchen, with drifts of vegetable peelings on the floor. But the dinner still tasted good.

The favorite salutation in Canadian rural districts seemed to be “Hello, Jimmy!” Names of towns, Highgate, Strathburn, Thamesford, Lambeth and Burford, sounded English enough and just fitted the scenery which looked the original of little English prints we have seen of the Avon and Thames. By the way, we crossed the Thames rive three times and a muddy stream it is. We have not seen, either in York State or Canada, a clear, clean stream such as we find all through Northern Michigan.

Coming out of London we passed Kellogg’s Toasted Corn Flakes building. From there to Brantford we took the Governor’s Road and I am sorry for the Governor and all Canadians. Just out of Brantford, two hundred six miles from Windsor, we saw the first speed limit board we encountered in Canada. Father declared some of them we saw later were not on his speedometer. Out of Brantford and after dark, we came up against our sixth washed-out bridge. We slid down a clay bank, wallowed across a clay swamp, and after unloading—first time on the trip—eight men pushed the car up the further bank. Mother ungratefully told them she did not like their country. We passed a Ford in the swamp, stuck with a broken spindle. We made it into Hamilton after a couple miles of winding road, down which the car coasted. Clay roads are bad for tempers and we were glad to stop for the night, having a mileage for the day of one hundred and forty-nine miles between 9:45 and 10:00 p.m.

Monday morning the sun was shining on the town of Hamilton, gloriously decorated for a Commerce Produce Industry Centennial 1813-1913. We had beautiful views of hills to our right for twenty miles or more. Through there is a great fruit country and we passed grape vineyards in plenty. Here we had a mighty interesting three-cornered race with a motor cyclist and an interurban limited. Beat them both on a five-mile stretch.

Just out of St. Catharines we stopped and watched two big Lake barges being locked through the Welland Canal. Seeing it straightened out our ideas of locks beautifully.

My first glimpse of Niagara Falls five years ago was from the train on the Canadian side, and this time we drove the car along the edge for half a mile, nearly up to St. Anthony’s Falls and back. The view of the Horseshoe Falls is much better from that side. The spray for a couple blocks is like a heavy rain so that we ducked under the blanket and peeked out, for the speed limit of four miles is rigidly enforced, rain or shine.

We had made two hundred and eighty-two miles in Canada when we tied on our Michigan pennant of blue and gold, attended to red tape at the Canadian end of the bridge, paid 10 cent toll and crossed into the U.S.A. at 12:10 Monday noon. The Customs officers looked at our papers, made us a lot of bother getting suit cases untied from the car and then let us go without the satisfaction of being examined. That is because Michigan people look honest. We turned into the park and started to leave for the nearest observation point, when a policeman demanded to know where our U.S. car license was. We declared it was on the back of the car under the mud but we had to scratch it clean and show him before he was mollified. He was quite indignant that we should expect him to recognize the Canadian license for a minute. He even recommended that we better run in somewhere and tet the car cleaned up—before we got hauled in! Honest, you would have thought it a gray car a rod away—so completely smeared was it with clay-mud. We spent two hours wandering around the Falls, with the air clearer and the sun brighter than I had ever seen it there. We girls saw enough amusing honeymooners so that we all vowed Niagara Falls would NOT be on our wedding trip itineraries, anyway.

Passing through Tonawanda we saw the Kelsey Hardwood Lumber Company’s office, and five acres of lumber yards which had burned over recently. We had ten miles of brick pavement out of Buffalo. The rest was state road, and we made the last forty miles to LeRoy, New York, in an hour and forty minutes. We have not had a foot of clay so far in the States.

Michigan used natural resources in her root and stump fences. Canada had wire fencing and white painted posts almost entirely. York state has stone fences.

This morning we visited the State Fisheries at Mumford. Not as well stocked at present as they have just made their largest shipments of fingerlings for this season. From there we drove to Lime Rock Stone Crusher. The manager conducted us all around and explained things to us—above the frightful roar of the machinery. The seams are eighteen feet deep. Each drill makes 115 feet a day, going down from six to eight feet apart, and is driven by air compressed in the main plant and conducted through pipes all round the quarry. The crusher takes rocks up to three feet in diameter and they come out on an endless chain cobble-stone-size and part are crushed smaller. The lime rock is too hard to be used by the chemical plants and its main use is in building railroad bed and highways. This plant is the largest of its kind in the world, turning out 3500 tons a day, working Sundays but not nights.

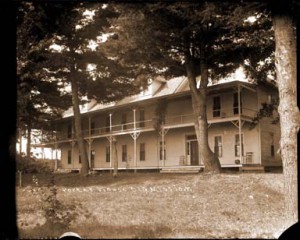

The total for the trip from East Jordan to LeRoy, N.Y. was 808 miles. We were on the road five days and had only one rainy day. The collapsible car top of the car looks so exactly like buggy tops that Father announced they were just for putting up if it rained. We all became expert at unfolding and extending it when showers began, and at unstrapping, collapsing and tucking it back into its boot when the sun came out again. Consequently, we four women folk arrived at the wedding of our cousin last Tuesday with badly sunburned noses. But that was a small matter. Our party left LeRoy Tuesday morning in a Buick and our Overland. Toledo cousins here on their own motor cycle honeymoon accompanied us. At the end of the day they proceeded on their own trip to New York City and Boston. The wedding was on the lawn under the giant locust trees beside the hundred-year-old cobble stone home of Father’s older sister, Martha Paine.

The new bridal couple left in our Overland with Father taking them to the boat at Buffalo, where they embarked for Cleveland and the new home. We expect to call on them on our way home through the States. Our present plans are to get us on our return way Monday, August 18th, and we will make calls on friends and relatives in Toledo, Cleveland, Kalamazoo and Grand Rapids. I certainly is proving a wonderful trip.

Sincerely,

Jennie Waterman

———————-

WATERMANS FINISH A DELIGHTFUL AUTO OUTING TRIP

East Jordan, Michigan

August 27th 1913

Dear Friend:

The return trip began Monday the 18th at 8:10 a.m. from LeRoy, New York from the home of Father’s younger sister, Rena Goldsmith. With fine roads and beautiful scenery we came into the vineyard country between Buffalo and Westfield. Grape vines were heavy with fruit on both sides of the road. Here, too, we had dangerously winding roads and went over the first real hills since leaving East Jordan. We came into Westfield at 4:30 with a flat tire. Decided to stay for half an hour to have it vulcanized—and stayed half an hour at a time until 8:30 when we decided to put up for the night. Another auto party were victims of the same garage—their car was overheated and behaving unpredictably—and we condoled with each other while the mechanics experimented.

People in cars from West Virginia, Massachusetts, Nebraska and California, Chicago and Cleveland met us and we hailed each other joyously when we sighted pennants. Some of the cars had more pennants on than we did—but always the home state pennant was proudly across the windshield, and after all, Oklahoma and Michigan could be close neighbors if they met way out in York State! It was no trouble at all keeping roads out East for sign boards and danger markers are put up by the Buffalo Automobile Club in New York and western Pennsylvania and by the Cleveland Auto Club in Ohio. We crossed the New York and Pennsylvania State Line 13 miles from Westfield, N.Y. and 3 miles from Northeast, Penna. Tuesday morning at 9:17 we had another punctured tire.

Just at the end of Girard’s main street the road dips and curves to cross a bridge over a deep gorge. There we had a grand, wide viw of the most picturesque country we ever saw; steep cliffs, a winding stream and bands given over to hot house uses.

We crossed the Pennsylvania and Ohio State Line two and a half miles from West Springfield, Penna and one and a half miles from Conneaut, Ohio. From Conneaut to Ashtabula it was level country. At Ashtabula we hung up our latest pennants and while Father took the tire to be vulcanized we located a restaurant and ordered dinner. The second course was being served when it occurred to us to take account of the cash in our four purses. We found the grand total to be twenty-three cents—even Gertrude B. had given her money to Father for safe-keeping! But Father came just then. We were delighted that he had found the same restaurant that we had for the food was very good.

Ashtabula is the largest iron ore receiving port in the world. While we were waiting for the tire we drove down to the ore loading locks and watched a vessel being unloaded. The machinery was wonderful. A great crane lifted an iron ore car, swung it through the air, poised it over a larger car, dumped it and put it back on the tracks. Jack-knife drawbridges were in action, too. Later, near Painesville, we saw an immense bridge and went under it through a fifty-foot tunnel.

Nearing Cleveland they were tarring the roads, which should be a good surface against dust for cars. We were looking for the newlyweds in their apartment on 92nd just a couple blocks off Euclid. But only 91st and 93rd showed as leaving Euclid. We asked a sulky drayman the way once, and then went around and met him face to face again. He need not have been so mad, though. He shook his fist in the direction we were to go then ordered us to follow him. We did, very meekly, and reached our port. 92nd started at a Y after 91st and 93rd had gone parallel a couple blocks! Ruth and Howard were looking for us, and we had a pleasant day in the nation’s 6th city. When we were ready to leave next morning Howard drove the machine fourteen miles to the city limits and we went on our way rejoicing as long as the good roads lasted. We were told fabulous tales of “elegant asphalt and brick all the way to Toledo” but we did not find it. And we had a record of three punctured tires for the day when we drove into the Overland Company’s garage in Toledo at 10:30 that night. We spent the night at the home of Charles Waterman, Father’s cousin and the tallest of the Waterman men, by the way. Repair work on the car gave us time to make other calls and to visit Tedke’s big grocery with its foods from all over the world dramatically displayed.

Friday Gertrude B. left us for visits on the side and we four went on to Galesburg, Michigan, where Mother’s people are. Coming through Battle Creek we were delighted with the decorations for Home Week. Several cars were beautifully trimmed. The prize float was white and yellow. The clown float was a sulkey and horse driven by a clown. A sign “Please Excuse Our Dust” hung a the back and his license card read “41,144H”. With our brightly colored twenty fluttering pennants we should have entered the parade ourselves. Of course the parade marshall might have suggested that we wash off the clay first!

Saturday night we had an auto party dinner with friends in Kalamazoo and went on to Breedsville where we visited old friends of Father’s who had all played in the famous Breedsville Band with him before he and Mother moved north. Sunday we reached Jenison Park by way of South Haven and Saugatuck over indifferent (bumpy) roads. From Holland through Grand Rapids to Big Rapids we had the very best roads of all—and then corduroy with all the “brass tacks” in evidence. I was left off at Big Rapids to attend to trunks Eva and I had left there from our summer course at FI, and the others again spent the night at the D.A. Bretz farm home near Evart.

Tuesday there were just three to make the last start and home run. The morning starts have been interesting all through—eighteen in all for the twenty-one days out—so we feel we have a welcome left for another time, most places. I gathered from comments, that it was pretty dark at 9:24 that night when the folks rolled up Main Street in East Jordan, so nobody saw the treasured pennants on our return. They came off before the usual Sunday drive. The milemeter registered 3600 miles on arrival. The reading three weeks ago was 1582, making the trip 2018 miles. Going was 818 miles, returning 1200 miles. Now that we are away from the dusty heat and excitement we are enjoying our beautiful trip all over again and planning how we will go next time. In the meantime it is wonderful to be at home in East Jordan, Michigan.

Sincerely,

Jennie Waterman

Written in pen:

Mrs. Clayton L. Arnold

623 Washington St.

Traverse City, Mich.

1955

Note: This account was written when Jennie Waterman (Arnold) was twenty years old. It was published previously in the Charlevoix County Herald, and in Michigan History magazine, 1950.