Goldie’s Fern is a giant among wood ferns, sometimes standing four feet high or more, its scaly stems arching in blue-green rosettes. Contrary to our expectation, it does not live in swamps but in rich woods, the soil often damp but hardly mucky. While not endangered, it is quite rare—few Northern Michigan residents have taken note of it—even if they have walked past it as they hunt for mushrooms or seek out deer habitat. To the unpracticed eye it is only a larger than average component of repetitious plant life upon the forest floor. Lacking flowers and colorful leaves, it does not attract our attention, perhaps a boon to its survival since it offers humankind little of value.

Except for some of us, that is. Dan Palmer, for one, finds the plant to be a treasure. Author of Ferns of Hawaii, Dan has been studying ferns and their relatives—horsetails and club mosses—for more than twenty-five years. Formerly a dermatologist, he was able to retire from medicine at a relatively early age and indulge his interest in ferns, a group of organisms overshadowed (quite literally) by the more showy flowering plants. Perhaps that was their attraction: there exists a whole group of living things, relatively ignored, inhabiting sheltered places near and far. Ferns beckon the curious mind.

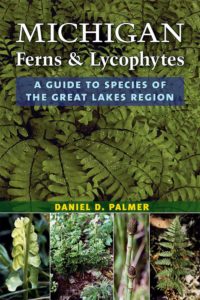

Renowned fern expert Warren Wagner of the University of Michigan mentored Dan in the early years of his interest. Later, after having traveled to such remote fern habitats as the rainforests of Indonesia, the mountains of New Zealand, savannahs of Africa, outback of Australia, and the islands of the South Pacific, Dan became an expert in his own right. His carefully researched Ferns of Hawaii has earned the praise of the small community of fern lovers world-wide. As a special gift to Michigan residents, he has just completed a new guide, Michigan Ferns and Lycophytes, recently published by the University of Michigan Press.

Renowned fern expert Warren Wagner of the University of Michigan mentored Dan in the early years of his interest. Later, after having traveled to such remote fern habitats as the rainforests of Indonesia, the mountains of New Zealand, savannahs of Africa, outback of Australia, and the islands of the South Pacific, Dan became an expert in his own right. His carefully researched Ferns of Hawaii has earned the praise of the small community of fern lovers world-wide. As a special gift to Michigan residents, he has just completed a new guide, Michigan Ferns and Lycophytes, recently published by the University of Michigan Press.

Though Dan married his wife Helen in Hawaii and brought up his three children there, he has strong ties to Northern Michigan. Brought up in Frankfort, he has a summer residence in nearby Leelanau County. For many years the custodian of a vast hardwood forest, he recently got out of that business, turning over a large acreage to the Leelanau Conservancy, that tract named “Palmer Woods.” Is it an accident that his forests nurture a diverse fern and club moss flora?

As if pulled along in the wake of a passing ship, several of us naturalists—Julie Medlin, Rick Halbert, and me, Richard Fidler–have become fern devotees, following Dan’s lead. It is hard to resist the call of these plants, especially when Dan is breathless with excitement about having found a rare hybrid fern he has not seen in some time. With such shared enthusiasm, it is not surprising that our party headed out in a forest one July morning to a location in Sleeping Bear in search of Goldie’s Fern.

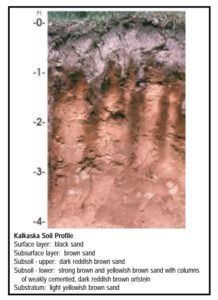

On the way we pass by fields of scant grass, juniper, and struggling trees, the black humus of the soil blown away or burnt away after the intense logging of the previous century. One fern grows there with a tenacious hold on the land: bracken. Ignored because of its ubiquity—it is found all over the world except in Antarctica—the species takes up more biomass than any other plant or animal species in the world. Favoring acid, well-drained soil, it is at home in Northern Michigan, especially in areas deforested by loggers and burned. Its crosiers bending upwards in spring, are said to be delicious when de-fuzzed and steamed, though concern has been voiced about carcinogens lurking inside. In Asia, where the fern is consumed in large numbers, stomach cancers are more common than in the West and accusing fingers have been pointed at bracken as a major cause.

Arriving at the Empire Bluffs parking lot, we head for the maple-beech woods growing upon the perched dune high above Lake Michigan. The spring wildflowers—the trillium, violets, Squirrel Corn and Dutchman’s Breeches—have long finished blooming, leaving less spectacular blooms like Herb Robert to brighten the trail. The ferns, however, are just hitting their stride. Their leaves, called fronds properly, are unfolding in coil-like fashion, forming fiddleheads for their resemblance to the scroll of a violin. We see the Evergreen Wood fern unfurling thus, sending up new fronds over last year’s leaves flattened by the winter’s snow. Dan confirms the identification by checking for the presence of dots called sori that lie near the margins of the fronds. They make the spores that blow about in the summer wind, seeking a favorable place to begin a new plant.

As with all things in biology it seems, nothing is straightforward about the lives of ferns. Spores only grow into little green chips of green that harbor male and female sex organs. Upon one warm or wet night (or day), a sperm with many tails will swim from the male organ to the female and fertilize an egg there. Then, as the fertilized egg divides again and again, a new fern arises above the forest floor. The fern life cycles suggest midnight trysts and passionate mating—sometimes between different species, even.

To Dan, that represents an exciting possibility: Could we find not only Goldie’s fern but a hybrid of Goldie’s and another wood fern? As we walk along, his eyes examine the Evergreen Woodferns carefully. Are there some Goldie genes concealed in the ferns all around us?

We pass other ferns, taking time to note their locations: Lady’s Fern, Intermediate Wood Fern, and the less common Christmas Fern and Common Polypody. Michigan has a diverse population of ferns, not as diverse as large states like California with its enormous number of specialized niches—deserts, mountains, rainforests, and prairies—but it still has a respectable array of species. About xxx fern species have been found in Michigan.

As we walk through an area of young maples, the ground bare of last year’s leaves, Dan bends over suddenly to examine something we had missed. He brings out his magnifier to get a better look and regards us gathered around with enthusiasm: A moonwort, he declares, Botrychium matricarifolium. The plant is scarcely two inches tall, its clustered spore-bearing structures overriding a single leaf. Spending most of the year locked deep underground, it puts up this green shoot in late spring in an effort to spread its spores to the wind. Remarkably, it is still visible this far into summer, for, like Spring Beauty and Dutchman’s Breeches, it has only a short time to share its above-ground presence with us. Such things are the treasures only botanists appreciate, their senses more attuned to the life cycles of things that neither do us no harm and nor provide us with benefit.

Goldies Fern surprises us. We top a hill in this hardwood forest, and there they are—scattered upon the forest floor, rosettes of green fronds growing higher than our waists. We check the leafy scales at the base of the stipe—the stem of ferns—to confirm a black mark bracketed within a light brown matrix. The leaves are acuminate, trailing gradually to a sharp point—that configuration unique to this wood fern species. We pause for a moment, glad to be at this place to see something so rarely seen.

Our moment of ecstasy does not last long. Dan is on his hands and knees examining a fern frond carefully. It might be, he says, It might be… We know what he is pondering: Is this fern a hybrid between Goldie’s and another wood fern? The answer to such questions so rarely asked by human beings takes on unexplainable importance. In a world of uncertain economics, uncertain politics, and uncertain environmental health, the pursuit of answers to questions about ferns seems like a waste of time to some. But to Dan Palmer, it is a voyage into discovery and wonder. And so it is for all of us who cherish the small things of Nature that lie beneath our feet.

Note to readers: Michigan Ferns and Lycophytes is available at bookstores and online now. Beautifully illustrated with scans of living ferns, it contains descriptions, distribution maps, identification keys, and fascinating information about the ferns, club mosses, horsetails, and spike mosses to Michigan. It is a delight for all naturalists with a spark of interest in this neglected group of plants.