By Stewart A. McFerran, Benzie resident and instructor of The Natural History of Great Lakes Fish for Northwestern Michigan College’s Northern Naturalist Program.

I took a job as a deck hand for Lang Fisheries of Leland Harbor. Ross Lang operated the Joy and the Frances Clark, both commercial fishing boats. As one might expect, a commercial operation means catching fish for profit. Unlike charter fishing operations, we worked until the ice clogged the harbor and the steel hull could no longer break a path through ice packed into Leland Harbor.

The Frances Clark was a classic high-decked Great Lakes fishing tug. Everything inside was dedicated to the lifting of nets. Nets could be set in the deepest part of the lake. When the net came in through the side near the bow, fish were taken out and put in boxes. The net was carefully stacked in a different kind of box ready for “set back” out the back of the boat.

The crew, Ross and I worked at a table near the “lifter”. Ross steered and I stacked the net in a box. On days when there were lots of chubs in the net, it was slow going, sometimes taking from first light until the afternoon to lift. The chubs, or Coregonus hoyi, are part of a genus including whitefish, cisco and lake herring. There were days we caught over a thousand pounds. I was a novice fisher but had the advantage of never getting sick.

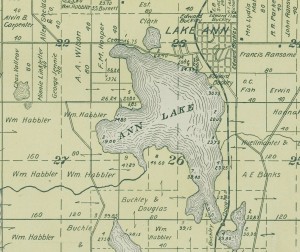

We fished from Northwest of North Manitou Island to Platte Bay, some of the same waters that Magdalene (Lanie) Burfeind fished in 1869. She kept her boat at Port Oneida and sold her catch to the crews of the steamers that stopped at Port Oneida. In this description of seventeen-year old’s Lanie’s fishing methods, written in 1869 and published in The Evening Wisconsin newspaper in October of that year, she had:

been the master of a handsome craft and a set of ‘gill nets’. She puts them out early in April and continues them till late in the Fall. She is out every day at daylight and again in the evening in all but the roughest weather. She takes a younger sister with her to help set and draw the nets. She often brings in a couple of hundred fine lake trout white fish… Her white mast and blue pennon is known by people far along the coast. Boats salute her in passing.*

At the time Lanie Burfeind fished, there were ten known species of Coregonus living in different parts of the lakes. Miss Burfiend may have caught and sold coregonids that were never described and included in the genus.

Coregonus hoyi and culpeaformis were the fish Ross and crew caught in the Manitou Passage more than 100 years later. As the net came in so did other fish and objects from deep dark places 300 feet down. A cod relation, the “big, bad” Burbot, also known as “lawyer” came in over the side with the hoyi catch. Spiky Stonerollers, stream boat clinkers and the occasional trout came in with the chubs but often nothing else but Coregonus hoyi. They had the deep dark lake to themselves. On bad days Ross sped up the lifter and the net came in empty. In 1984, a net could stand on the lake bottom and catch nothing. Not so today; Bushels of quagga mussels foul nets as they filter the same zooplankton preferred by coregonids.

After months of releasing “chubs” from the net I began to be aware of the variation in color and shape. There were very slight differences in hue in the silver of the sides. Sometimes I wonder if I was witness to the last of a species of Coregonus that was sold as a “Chubby Mary” at the Bluebird in Leland. It is my understanding that the popular drink is no longer made with C. hoyi but with C. artidie. Not having a degree in mixology I can’t be sure.

(Editor’s note: Upon further inquiry, the “Chubby Mary” is still available for consumption at the Cove restaurant in Leland. Described as “part appetizer, part drink,” Chubby Mary is made with the house blood mary mix, a pickle, two olives, and lemon garnish to accompany the fish, a smoked chub served with pita chips. The servers were unsure what species of Coregonus is now used.)

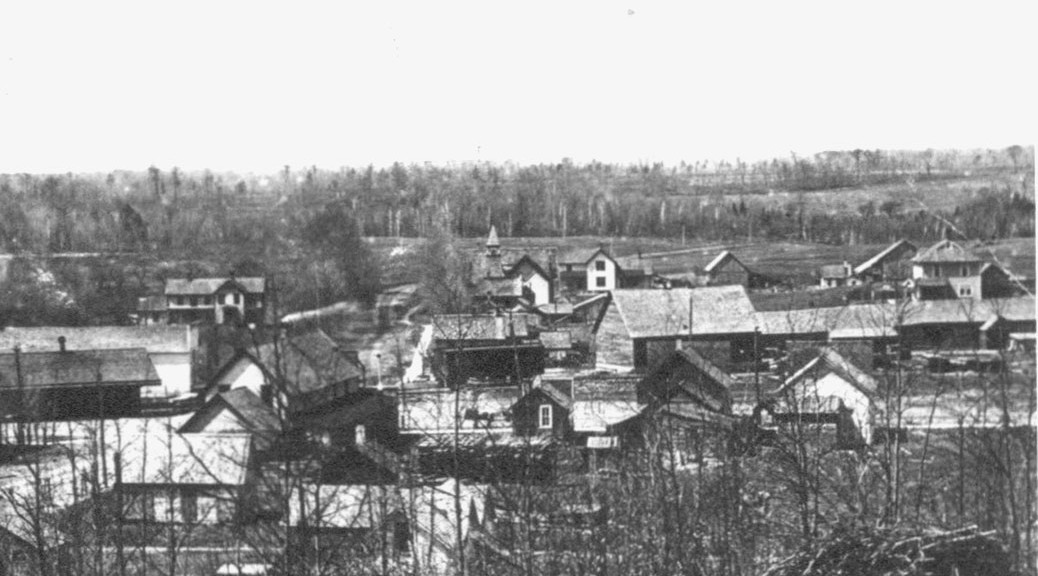

The US Fisheries Commission reported in 1890 that whitefish and lake herring, (both within the group Coregonus), accounted for 58% of the commercial catch in Lake Michigan. At the time there were eleven commercial fishing boats operating in Benzie County and eleven in Leelanau. None in Grand Traverse. The Booth Company was developing a wide network to exploit fisheries and fishers in both American and Canadian waters.

Coregonus nigripinnis was found in great abundance in the deep waters of Lake Michigan in 1890. Blackfin whitefish were “sought mostly in steam vessels and are taken in gill nets set 60 to 110 fathoms deep.” The longjaw whitefish (C. zenithicua) lived at similar depths but did not have black markings on the fins.

The Manitou Islands have little in common with the Galapagos Islands other than the fact that a unique group of species evolved over time in isolation. Diving in the Galapagos I saw many fish and I talked with fishers unloading shark fins. I saw finches flitting about under the table of the café at Puerto Ayora. As a coffee drinker I could not miss them under foot as they evolved a taste for biscotti. It was fascinating to see that same assemblage of species that Darwin had so famously observed.

As the ice receded from the Great Lakes the coregonids were at the margin 10,000 years ago. Like Darwin’s finches they were separated into different populations as the lakes rose and fell. Each group changed as the ice continued to melt. The populations responded to local conditions and donned different colors and shapes. Deepwater blackfins became the dominant planktivore in the fathoms of Lake Michigan. The pelagic longjaw coregonids are hard to spot in the deep remote places of the big lakes, but, like the finches, changed in response to the environment.

While inhabiting remote niches and not making big splashes, the Great Lakes coregonids are a group of fish with many names that reflect the wide distribution and importance of the group. Other species of Coregonus are: kiyi, bartletti, johannae, reighardi and hubbsi. Hoyi are thought to still be present in Lake Michigan and sometimes called “bloater chub”. The blackfin and shortjaw can still be found in Lake Superior. Coregonids evolved the ability to move in the water column by regulating buoyancy as they fed on zooplankton.

Over time the Great Lakes fishing tug was perfected to a point where fish numbers were threatened. The “Lifter” was developed to pull nets from the deep regions of the lakes. The covered decks on the tugs allowed the fishing operations to continue into bad weather. One such vessel is on display at the Sleeping Bear National Lakeshore in Glen Haven near where Lanie fished.

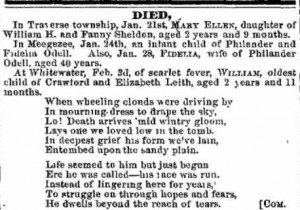

When the steamer Normon lay wooding up at Port Oneida in 1869, it was recorded that Miss Burfeind had delivered fish: “The clerk at the office tipped his hat to her as if he was in the presence of a Duchess. ‘That’s the smartest girl in Michigan,’ said the engineer as she passed out the gangway. The girl gave no heed to admiring glances and compliments that followed her, but straightaway sought her little fish cabin where she was mending nets, by the shore.”*

The decline of coregonids took place over many years. The introduction of chemicals and invasive species changed the ecology of the Great Lakes. Tiny eggs of C. kiyi and C. hoyi left to drift in the water column were gobbled up by unwanted intruders. The free floating C. zenithicus eggs were acted on by numerous kinds of chemicals. Ecological change has come to that water column in ways that biologists are still trying to understand, but it is clear that the diversity of the Coregonus group has been reduced since 1869.

It is unfortunate that the group has been so reduced. More than any other assemblage of organisms they evolved in the Great Lakes and represent the lake environment as true natives, just as finches represent the Galapagos Islands.

Stewart Allison McFerran has a degree in Environmental Studies and worked with Frankfort students on a robotics project. He led an Antioch College environmental field program to the Great Lakes and worked as a naturalist at Innisfree. He worked as a deck hand for Lang Fisheries and currently is an instructor at NMC Extended Education program. He lives on a Benzie stream. He did graduate studies in science education and was a Research Associate at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. He grew up on a Lake in Michigan where he caught and released many turtles from his rowboat “Mighty Mouse”. McFerran is a regular contributor to Grand Traverse Journal.

*Article on “Lanie”, Semi-Weekly Wisconsin (Milwaukee, Wisconsin), Sat, Oct 16, 1869, Page 3