by Stewart A. McFerran, Benzie resident, outdoor enthusiast, and regular contributor to Grand Traverse Journal

What does it mean to be “sustainable” in industry or practice? The passenger pigeon industry came to an end as a consequence of UNsustainable practices. The Petoskey area is often cited as the last mass roost in 1878, but there was a mass roosting of passenger pigeons on and around the Platte River in Benzie County in 1880.

Passenger pigeons made a big impression as they flew in huge numbers across North America. This plain pigeon was a unique species because of sheer numbers and gregarious nesting habits. From all reports, the flocks could blot out the sun, their nesting grounds spreading out for miles.

Simon Pokagon, a Potawatomi tribal leader, author and Native advocate, had observed (and is frequently quoted on) the migrations of passenger pigeons in the Manistee area since 1850: “I have stood by the grandest waterfall of America and regarded the descending torrents in wonder and astonishment, yet never have my astonishment, wonder, and admiration been so stirred as when I have witnessed these birds drop from their course like meteors from heaven.”

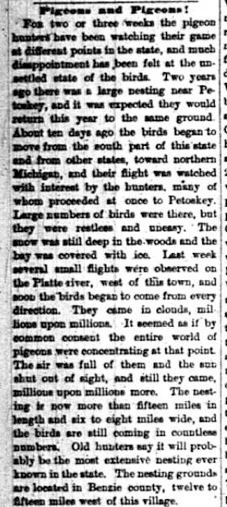

According to reports published in the Grand Traverse Herald, April 1880, a network of spotters located a salt spring in Benzie County that would attract large flocks of the birds. Mineral rich water bubbled out and over a mound and down a slope. Millions of pigeons congregated in this area. The owners allowed pigeon netters to catch passenger pigeons there for a fee:

“Last week several small flights were observed on the Platte River. They came in clouds millions upon millions. It seemed as if by common consent the entire world of pigeons were concentrated at this point. The air was full of them and the sun was shut out of sight, and still they came millions upon millions more. The nesting is now more than fifteen miles in length and six to eight miles wide, and the birds are still coming in countless numbers. Old hunters say it will probably be the most extensive nesting ever known in the State.”

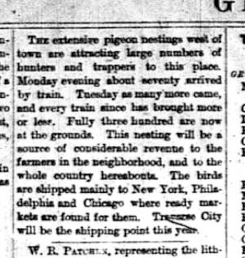

The large groups of hunters that flocked to Northern Michigan to shoot the remaining passenger pigeons arrived by train. They were well practiced in the dispatching, collecting, preserving and shipping of passenger pigeons. The market for the birds was well established in New York, Philadelphia and Chicago.

What market, you might ask? Passenger pigeons were on the menus of American colonists from the start. At one time, the birds were considered a godsend and kept starvation at bay. Other times passenger pigeons were a delicacy. Pigeon pies were popular and Delmonico’s in New York served passenger pigeon. Pigeons were salted, smoked and pickled. (Greenberg, 2014).

“Fully three hundred (hunters) are now at the grounds. This meeting will be a source of considerable revenue to the farmers in the neighborhood and to the whole country hereabouts.”

Conservation efforts to preserve and prevent the ill-treatment of the birds proved ineffective, a matter of too little, too late. The 1870s saw an increase in public awareness on the brutality of these hunts, leading to protests against trap-shooting. Various states enacted laws to curtail the slaughter over the next twenty years. In 1897, a bill was introduced in the Michigan legislature asking for a 10-year closed season on passenger pigeons. Similar legal measures were passed and then disregarded in Pennsylvania and New York. By the mid-1890s, the passenger pigeon had almost completely disappeared, and was probably extinct as a breeding bird in the wild. (For more information on conservation efforts, see W.B. Mershon’s The Passenger Pigeon, published in 1907, and available freely online.)

Martha, thought to be the last passenger pigeon, died on September 1, 1914, at the Cincinnati Zoo.

Benzie hunters had the distinction of hunting some of the last passenger pigeons. They had help from gun toters and netters from afar. But we can learn a lesson from Martha: No one will ever hunt a passenger pigeon again. The passenger pigeon will never be counted during a Benzie Christmas Bird count because our ancestors did not have the foresight to use sustainable practices.

Sources:

Grand Traverse Herald, April 1880.

Greenberg, Joel. A Feathered River Across the Sky. New York: Bloomsbury, 2014.

Mershon, W.B. The Passenger Pigeon. New York: The Outing Publishing Company, 1907.

Wikipedia.

Were there any videos of Martha taking at the Cincinnati zoo?

Great question, Rob! We did some digging, but alas, we don’t think Martha’s song was ever recorded. She passed in 1914, so the technology existed to capture her voice, but I could not find a known recording. Her remains are on display at the Smithsonian, and she is central to an ongoing debate about “de-extinction.” That’s an interesting topic for more research, if you’re up for it! Scientists at the Smithsonian are quoted as saying the living pigeon most closely related to the Passenger is the band-tailed pigeon, and there are a number of recordings of that bird online. Thanks for reading and commenting.