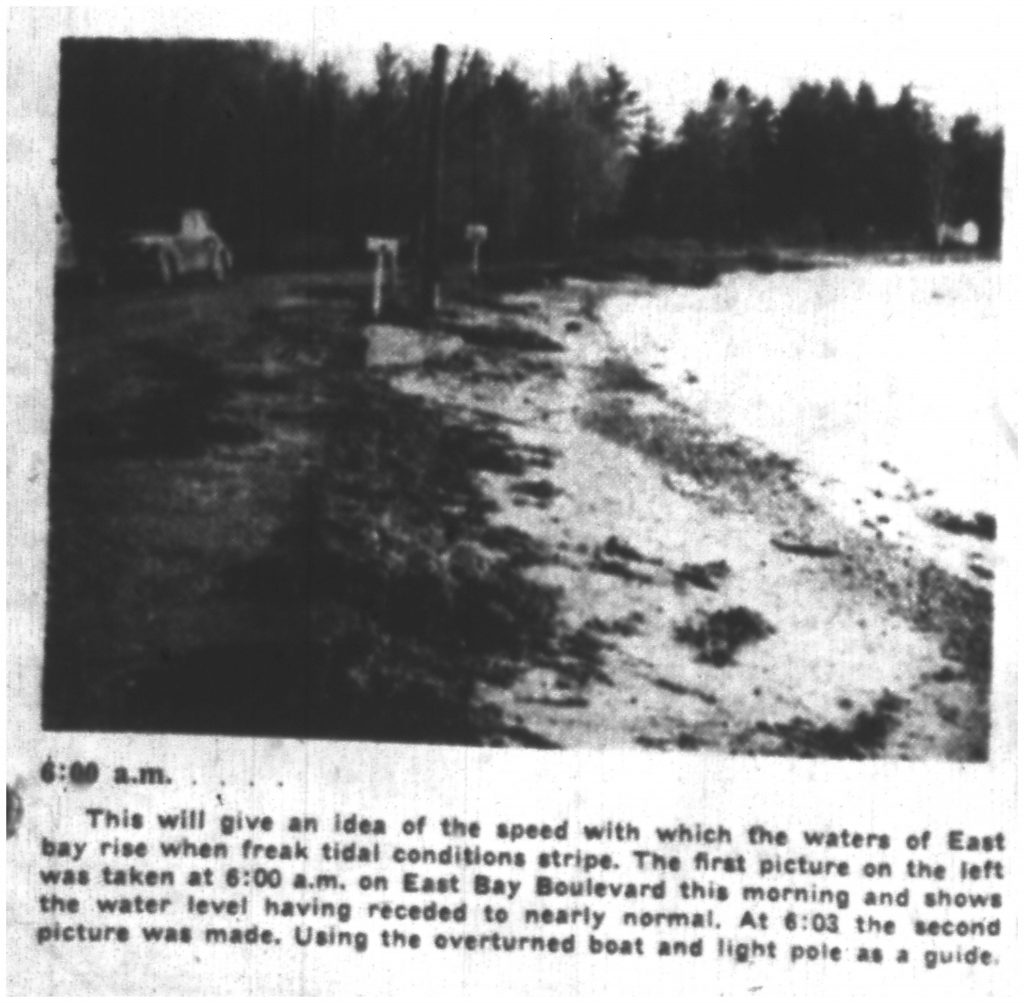

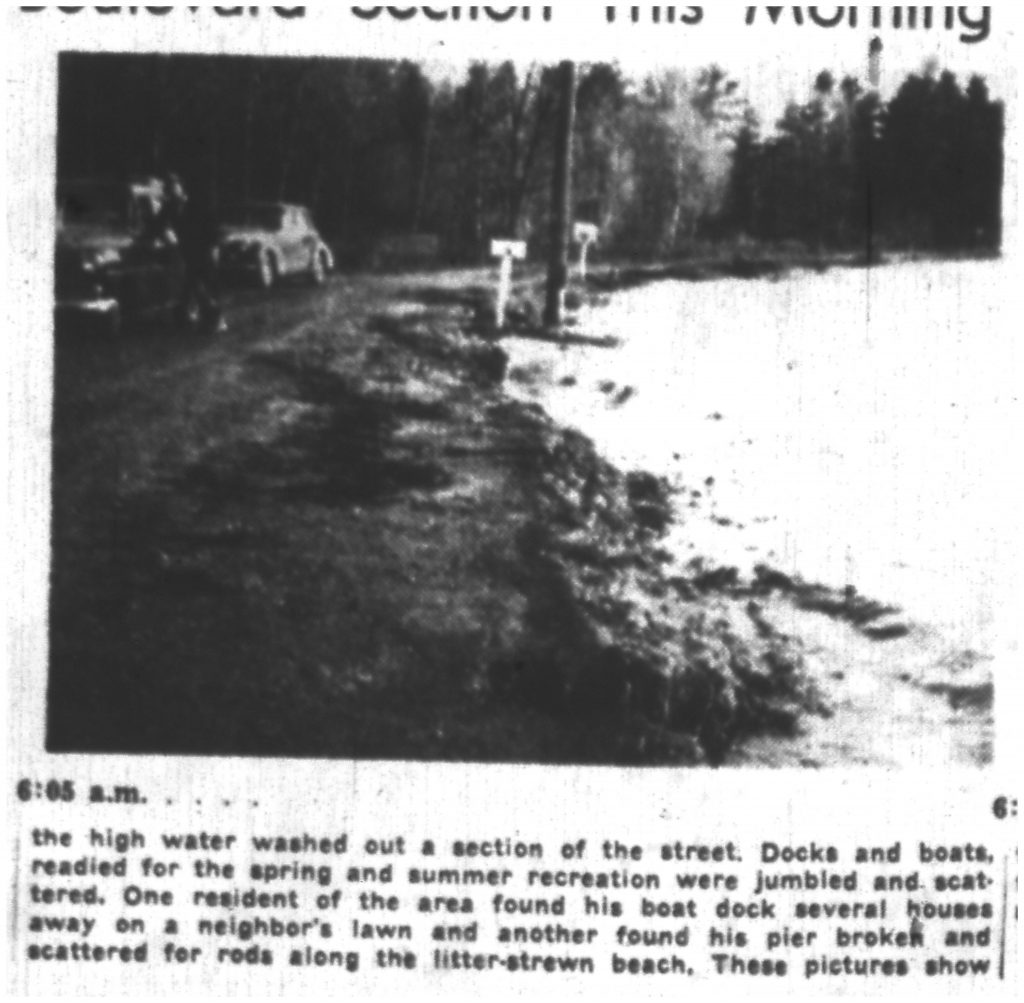

How many times has it happened? Along East Bay, usually at night or early morning, the water surges up, rising four feet or more from its normal level, only to subside within minutes. In the past, roads have been flooded, docks floated away, and debris swept into the water. Houses and cottages have been flooded and cars damaged by the flooding such that they had to be towed away for repair. West Bay gets them, too, but East Bay, especially at the south end, from Five Mile road west to the Birchwood area of Traverse City have been especially hard-hit.

The 1950’s experienced a number of these events, not just locally, but throughout all the Great Lakes. At first, no one knew what to make of them: newspapers called them “Tidal Waves,” often using quotation marks since everyone knew they had nothing to do with the tides. The only similarity is that the water rose somewhat gradually, and not with an abrupt crash of giant waves on the shore. In 1952, the Traverse City Record Eagle declared no one knew what caused them, but that observation was soon to change: a surge of water with immense waves swept up on the Chicago shore on June 26, 1954, causing the deaths of ten persons. That tragedy sparked interest among scientists studying the phenomenon. They would soon uncover the causes.

Gordon E. Dunn, Meteorologist-in-charge of the Chicago office, realized that, on past occasions, the surges always occurred after the arrival of a pressure increase associated with a rapidly moving storm front coming from the north. On July 6, 1954, just ten days after the devastating surge described above, conditions looked nearly identical to those of that day. Based upon his understanding of the event, Dunn issued the first seiche warning. Somewhat to his surprise given his scant knowledge, a moderate seiche did strike Chicago, one that caused little damage, much to the relief of all.

Since those early times, we have learned much more about seiches. They are associated with fast-moving storm lines, especially those moving faster than 50km/hr. There must be a significant pressure rise associated with those lines, with a long fetch of water covering the entire width of a body of water—Lake Michigan or Grand Traverse Bay–making for more the most dramatic events. One factor Dunn did not understand was the most fundamental thing of all: storm surges bounce off shores and send reflected waves outward to interact with those coming in. It is like a basin of water with a water disturbance that reflects off the sides, sometimes building into surges that are magnified by the coming together of different waves. Surges and the receding of water can go on for days as waves interact, just as water in a basin takes time to settle if it is disturbed. All of this happens during seiches.

East Bay presents another aspect of seiches. It has vast shoals—shallow areas—that extend from the south and west shores. When rising water strikes them, waves grow taller, driving farther inland. One of the descriptions of a seiche claims that the water rushed 30 to 40 feet inland from its usual position, but only in areas at the base of the Bay. This “shoaling” effect is known to increase the severity of seiches.

East Bay also presents an obstructed range of open water (a “fetch”) that enables waves free travel down its length. By contrast, West Bay has a narrowing at Lee’s Point on the west side and Bower’s Harbor on the east, after which it widens at the south end. Contours of the land also affect the severity of seiches, and East Bay seems especially suited to maximize high water surges.

This is not to say West Bay has not experienced them. On April 1, 1946, a resident of Bay Street in Traverse City reported the water level rose two feet before subsiding. An older story is told that in March, 1891, the city had been withdrawing water from West Bay for household use by means of an intake pipe that extended two hundred feet from the shore under twenty feet of water. When the pumps started racing one morning, it was realized that no water was being moved at all. Upon breaking the ice that covered the intake, it was discovered that the water had receded to the point that the mouth of the pipe wasn’t in the water at all. Soon after, water levels rose, and residents were able to get water for their morning coffee. The peculiarity of this event—occurring when the Bay was frozen—sets one to wondering if some factor besides a seiche wasn’t operating.

East Bay experienced three significant seiches in the two years 1952-53. The May 5, 1952 seiche is interesting because we have access to hour-by-hour data about wind speed and direction. Hour-by-hour after midnight the wind direction changed: 1:00 AM: out of the East at 7 mph; 2:00 AM: out of the west at 7 mph; 3:00 AM: out of the south at 10 mph: 4:00 AM: out of the west at 8 mph; 5:00 AM: out of the north at 12 mph. The wind direction stayed out of the north after that time for the rest of the day. Note the time of day: after midnight and early morning. For reasons not completely understood, the biggest surges of water tend to happen in early morning up to noon. Also note that the wind direction jumps from one direction to another, finally ending with a strong wind out of the north. The effect is to pile up water on one side of the Bay, only to have it rush in from the north. Given the contours of that body of water, that is exactly what you would expect in order for the biggest surge of water to occur at the southern end.

Residents on the south shore of East Bay notified the sheriff of the flooding shortly after 4:00 AM, a time fairly consistent with the wind change out of the north. After the first surge, water rose again and again, but never reached the high water mark of the first rush. That behavior goes along with our present understanding of seiches as disturbances in a closed basin with waves that reinforce each other at times.

When will the next seiche be? Who can say? We should beware when a fast-moving storm line moves in from the north associated with rapidly rising air pressure. The National Weather Service now issues warnings when conditions are favorable for water surges and high waves, and persons living in vulnerable places should take precautions to protect their lives and property. It has been some time since the last big one and it is easy to become complacent in the absence of memory. After all, Nature acts whether we are ready or not for what she gives us.

![Craspedacusta sowerbyi, a freshwater jellyfish native to China that is now a world-wide invasive species. Image courtesy of OpenCage (opencage.info) [CC BY-SA 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://gtjournal.tadl.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Craspedacusta_sowerbyi_by_OpenCage-300x300.jpg)