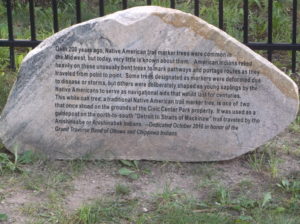

Congratulations to library patron Elizabeth, who successfully answered last month’s Mystery Photo! Indeed, the trail marker tree at the Grand Traverse County Civic Center was part of a trail that spanned from the Straits of Mackinac to Detroit.

Congratulations to library patron Elizabeth, who successfully answered last month’s Mystery Photo! Indeed, the trail marker tree at the Grand Traverse County Civic Center was part of a trail that spanned from the Straits of Mackinac to Detroit.

As a fumbling collector of automobile-related relics, I had long wondered why I couldn’t get road maps before the 1930’s. It took some time for me to understand that the folded maps offered free by the oil companies—Gulf, Shell, and Mobil—didn’t come out until the thirties. Before that time, I wondered, how did motorists navigate the highways in the first three decades of automobile travel?

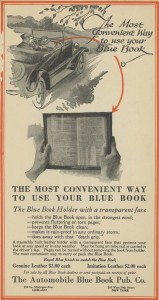

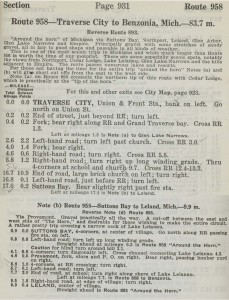

My discovery of the Automobile Blue Book answered the question. Not to be confused with the Blue Book that gives the cash value of automobiles, the Automobile Blue Book was a navigational aid to motorists at the dawn of the automobile age. Through primitive maps and step-by-step written directions, it outlined routes from one destination to another, Traverse City to Benzonia, for example, or Traverse City to Old Mission.

My discovery of the Automobile Blue Book answered the question. Not to be confused with the Blue Book that gives the cash value of automobiles, the Automobile Blue Book was a navigational aid to motorists at the dawn of the automobile age. Through primitive maps and step-by-step written directions, it outlined routes from one destination to another, Traverse City to Benzonia, for example, or Traverse City to Old Mission.

Blue Books contained much more than directions about how to get from one place to another: They offered information about roads (dirt, gravel, crushed stone), steep grades, and blind curves, and recommended the best and safest routes to drivers and navigators. Along some roads they cautioned travelers about boulders and washed-out places. With the unreliable machines of the time, information about garages and hotels was included within the directions: A breakdown requiring repairs and an overnight stay could occur anywhere.

Successful auto trips required two partners—the driver and the navigator–since the driver cannot take time to keep looking at the book and the mileage while avoiding oncoming traffic, cattle blocking the highway, or ditches that loomed on either side of the road. An advertisement for a celluloid protector for the Blue Book showed a man in the driver’s seat with his spouse alongside, patiently (we would presume) giving instructions to her husband. Of course, women drivers were not unknown in the twenties either, and roles could be reversed.

Successful auto trips required two partners—the driver and the navigator–since the driver cannot take time to keep looking at the book and the mileage while avoiding oncoming traffic, cattle blocking the highway, or ditches that loomed on either side of the road. An advertisement for a celluloid protector for the Blue Book showed a man in the driver’s seat with his spouse alongside, patiently (we would presume) giving instructions to her husband. Of course, women drivers were not unknown in the twenties either, and roles could be reversed.

At first, most cars lacked odometers altogether; they had to be purchased as an accessory. A starting point from each city center was designated—in Traverse City the junction of Union Street and Front served for all routes. Mileage was zeroed out at that point, all subsequent turns and landmarks measured in tenths of a mile. Like a modern GPS system, the navigator informed the driver of the route ahead, turns and distances, presumably in a calm voice that did not betoken a lack of confidence in the driver.

The Blue Book educated travelers about the areas to be explored. Of Old Mission Peninsula it generously wrote:

Grand Traverse peninsula [sic] extends 18 miles into Grand Traverse bay and varies from one to three miles in width and in height from bay level to several hundred feet. With its rugged shore line, many promontories, sandy beaches and sheltered bays, it is the most beautiful region in southern Michigan.

One can imagine travelers from remote places reading the Blue Book to educate themselves about the places they passed through. It was far more than a navigational aid: it was a book full of answers, much as our internet toys are now.

Upon receiving my Blue Book via an internet sale, I resolved to set out on a journey to catch the flavor of auto travel in the 1920s. Of course, it wouldn’t be the same: my Honda with its climate control system, stereo radio, comfortable seats, and relatively noiseless and dust-free operation would not capture the same sense of adventure (which, no doubt, was associated with the likelihood of misadventure) that motorists felt so long ago. I would not have to stop to fix flats as auto travelers frequently did in that era, in part because horseshoe nails no longer littered the roads. Highways and byways would be paved and smooth without the hazards of poor design, hasty construction, and the absence of highway warning signs (which hadn’t been standardized yet). In case of an accident I count on four air bags deploying at once while a Model T lacked seat belts and the advantage of a cabin protected by a cocoon of metal that can withstand crashes at 40 miles per hour. Perhaps all of that safety gear was not necessary given that the speed limit in Michigan and practically anywhere else in the country was slower than a horse’s gallop, 25 miles per hour.

One of my Backspacer friends (the Backspacers are a tiny group of persons interested in local history), Marly Hanson, agreed to act as navigator during our journey. Possessing the preciseness of mind and the devotion to detail of a former reference librarian at the Traverse Area District Library, she was well suited for the job. While we were never in danger of getting lost, we would often have to make sense out of outdated instructions. After some consideration, we decided to go to Leland by way of Suttons Bay and Lake Leelanau, a short jaunt that could be done in a couple of hours or so. And so, with Blue Book in hand one early September day, we set out on our adventure.

We zeroed out the odometer at the corner of Front and Union in front of the 5/3 bank, already feeling a sense of connectedness to our history since a bank had stood there in 1920, the Traverse City State Bank, founded by Perry Hannah, one of the founders of our town. However, we quickly realized that the Grandview Parkway did not exist at that time, an extended Bay Street carrying the traffic towards Leelanau county. Still, odometer readings were in fairly good agreement with the book as we crossed imaginary railroad tracks—now the TART trail—as we passed 72 which led up the long hill to the west of town.

At 2.6 miles we were told to turn left, onto what is now Cherry Bend road, and this we did. A church was at the corner as indeed it was the West Bay Covenant Church. We expected to turn away from the bay here since the road from Traverse City did not proceed directly to Suttons Bay as it does now. It went inland and rode the ridge high up from the water.

At approximately 9.7 miles we passed through a 4-corners with school and church—now Bingham–those buildings having been converted to the township hall and to a residence respectively. It was a straight sail to the end of the road and a large brick church, St. Michaels, in Suttons Bay. The trip had been easy so far, the roads no longer gravel but paved and straight for the most part. Old maples lined the highway, still standing after having been planted by local farmers ninety or more years ago. They were showing signs of age, premature aging, perhaps, due to the salt applied in winter.

The entrance to Suttons Bay was different from now, the old road joining up with the modern one before the fire station which still stands, though now converted to a restaurant. Resisting an urge to spend time in the village, we proceeded out of town, up a “long, winding grade”—surely a staggering job for the engine of a Model T laboring to bring the car through gravel on a hot summer’s day. Reaching the top, we settled down for the long descending trek towards Lake Leelanau, that name being “Provemont” in 1920.

Before we crossed the channel, we read a cryptic note: “4-corners; turn diagonally left. Cross channel connecting Lake Leelanau 4.3” The 4-corners still remains, but there is no possibility of a diagonal left turn: the bridge extends straight-ahead. Leaving town, we see that Main Street crosses our highway: Could it be that the bridge had been moved to the north, separating “Main Street” from the passage across the narrows? We would learn more on our return.

Leland at last! We turned right, away from the waterfront to the center of the village, presumably a plot of land where the courthouse stood. Fairly recently that institution has been moved outside the village to a location along the road we had just traveled. Forlorn as if awaiting its possible demise, an old brick building with barred windows stood in a mowed field–the county jail–a vestige of the rule of law in this place. The center of town has moved from here to the busy commercial strip along M-22 and in Fishtown.

Marly and I stopped to get lunch and serendipitously met a friend, David Grath, who had information that would help us understand the mysterious directions given us in Lake Leelanau. Attracted to this area as a youth, David has explored the northern parts of Leelanau county since 1957, using his geographical knowledge to build an international reputation as a landscape painter. Keenly interested in local history as well, he tells us the bridge has been moved some time ago to the north. “If you go down by Lake Leelanau St. Mary’s cemetery to the dock extending into the narrows and look down, you can see the concrete slabs that made up the foundation of the old bridge. Main Street, used to be the main drag through town, only after they built the new bridge, it became a side street.”

We got in the car and returned to Lake Leelanau, eager to see if evidence of the old bridge can still be found. We passed the school and wound down a moderately steep hill to a dock that extended into the narrows. Walking out on it and looking down into the water, we saw slabs of concrete, surely relics of the 1920 crossing. The road on the other side would have had to bend diagonally to meet the bridge as the directions declared. Upon reaching the west bank, Main Street would have carried traffic through the tiny town: only a store and post office were mentioned as landmarks to look for. The post office is now gone, having been moved across the highway to St. Joseph Street, though a small frame building looking old enough to serve as “the store” remains. Provemont—Lake Leelanau—was not a major stop for travelers in 1920 or in 2014.

So it was that we completed our day of travel following directions given in our Blue Book. Without need of wiping the dust from our faces or the perspiration from our brows, we returned to Traverse City the direct way, along the Bay. Our journey was without the romance of early automobile travel, but still provided the smallest glimpse into how motoring used to be. We decided we would plan another Blue Book guided trek to a new destination in coming weeks. Who knows what relics of history will be illuminated in that adventure?

Note: Readers may visit the Woodmere branch of the library to inspect this Blue Book in the Nelson Room. Pages may be photocopied for those wishing to plan an expedition using Blue Book instructions. Happy motoring!

Richard Fidler is co-editor of Grand Traverse Journal. The image within the header is of Provemont, the “ghost town” of Lake Leelanau, and the steamer SS Leelanau, ca. 1908; Image courtesy of Don Harrison, Up North Memories, https://flic.kr/p/s6YaBg

Did you ever ride down to Traverse Point and back by way of Old Mission, all in one summer evening and night? If not, one of the freshest, most charming pleasures awaits you that ever your life held. Give your imagination the rein for a little space, and in fancy take the trip with us, to-day.

It is verging on five o’clock p.m. when we leave Traverse City. The sun is dropping towards the western hills, and sending long level golden beams into the eastern belt of pines and oaks as we leave the town behind, and sweep around the bight of the bay to the Peninsula. The bay is a misty blue with long lines of sparkling waves rushing shoreward, for though the air is warm with a languid, luxurious August heat, there is a brisk breeze from the northwest that sweeps through it—cool, bracing, exhilarating. In a few moments the town is dim behind us,–white houses, mill stacks with their plumes of smoke, church spires, and the castle-like walls of the asylum all melting together into the dim outlines. With swift and steady stroke our horses’ hoofs fall upon the hard, level road, and the speed of our going, with the rush of the wind in our faces, makes us feel as if it were wings instead of feet that are bearing us onward. The pines and cedars have closed in on both sides of the road. The air is spicy with resin and balm. All the little nooks are ablaze with goldenrod, blue with wild asters, or white with yarrow, that “dusty beggar, sitting by the wayside in the sun.” Now and then, a pretty clearing opens on the right, with a cosy white farm house set down in its bit of orchard, or green meadows, with a bright bed of flowers by the door, and beyond, fields of corn standing stately and tall in serried ranks, like soldiers on parade. Then the wood closes in again with its sweet, dark greenness. To the right it is close and dense. To the left is always the bay, so near we could toss a pebble in it through its fringe of birches and cedars. The wind freshens and the white caps dance out beyond the pebbly shallows. The crisp waves run up the beach and fall with a musical crash on the shore. Marion Island begins to loom large and green ahead. The little haunted island shows its fringe of bushes and stunted pines more clearly. The bay shore begins to take a great curve. The islands are abreast and then drop astern. The sun is shorn of his beams, and, a great glowing ball of fire, drops below the purple hills. A sudden, dewy breath as of twilight and the coming night sweeps out of the thickets. Tall pines stand in stately colonnades along the beach. There is a dock, ancient and wave-worn, running out into the water. This must be Bower’s Harbor, and we look out towards the haunted island, half expecting to see the ghost of the old Sunnyside come steaming out from behind the bluffs as she speeds to her old landing place. But no. Her timbers strewed the beach of Lake Michigan long years ago, and bluff Captain Emory sleeps his last sleep somewhere under these northern pines, and for her there has never been given a ghostly resurrection. On and on, the road sweeps around o the west and climbs a steep way cut on the side of the bluff, so near and so overhanging the water that the spray from the tips of the great green curling waves now coming in falls over us. The stout horses tug and bend to their task, and presently we are out on the top of the highlands, and the world lies open and fair before us, and this is Traverse Point.

What shall we say of it? Here are the beginnings only as yet of the improvement of one of the loveliest spots for summer homes in all this beautiful Resort Region. It is not fair to tell now of what is,–for that is changing so rapidly to the far different what-it-will-be. These pretty cottages rising here and there are only the avant couriers of uncounted others to come. Here is a children’s paradise, where all the summer through the little ones may gather roses for their cheeks, and strength and litheness to their supple limbs. Here—but why foretell? The swift years are telling the story of them both,–beautiful Traverse Point and fair Ne-ah-ta-wan-ta, “placid waters.” What will never change are rose of dawn and gold of sunset, silver glory of moonlight and purple of twilight, misty gray of summer rains and strength of wild waves when the winds send them sweeping in from the northwest in long lines of foam crested rollers, sparkle of blue under the noonday sun and glint of stars in fathomless depths of midnight in heaven above and water below,–a thousand variations of tint and form, of sound and motion, of shadow and light, and all beautiful beyond expression.

But time flies; we must not stop for rhapsody.

Back to the eastward we go and are off across Peninsula. The west is all aglow with gorgeous sunset hues of orange and crimson and dusky gold. There is a strange sense of wide expanse and unwonted freedom. We look to see why, and find it is because there are no fences in this township.

“How beautiful it is!” we say to each other. Here is a wide stretch of meadow land; just beyond it melts into a yellow stubble where the wheat was not long ago; then acres of silvery oats and then again the corn, rustling in the evening breeze, while again great patches of potatoes—green tufts, dotting the well-tilled brown soil, come down to the very wagon tracks. It is a great Acadian garden. The road winds and turns. It seems further than we thought. We must have come out of our way, for part of the time we are surely going back on our former direction. Shall we stop and inquire? No. It is fun to be lost in Peninsula, for we can’t get far away without getting into the water, and we must come out somewhere. So on we go in the fast gathering twilight. We are in the midst of the great Peninsula fruit farms. Far and wide on either side stretch the orchards. Those—green and glossy in the dim light—are cherry trees; they lost their ruby fruitage long ago; these are pears—loaded down, and with their branches propped to keep from breaking, and already the air is getting spicy with their ripening; yonder are plum trees, more purple than the purple twilight shadows with the bloom on their masses of fruit,–and everywhere are apples,–trees gnarled and knotty with age and crimson with clustering fruit,–trees young and vigorous and heavy with golden treasure,–surely the fabled apples of the Hesperides were not so well worthy of fame as these. There are handsome farm houses set down among these orchards. The light is dim now, but we can see and feel evidences of thrift, of comfort, and of substantial competence. Lights twinkle here and there through the trees. The road is hilly now, and we go swiftly up one rise and down another, till soon the road bends again and we sweep out on the East Bay shore. We are at Old Mission.

Here we stop for a little rest before we fairly start on our homeward way. We sit under the great maples at the Old Mission house, and watch the far off stars, and the distant lights across the bay at Elk Rapids, and listen to the whispering of the waves down on the beach and the moaning of the wind in the trees overhead, and dream. By and by the moon rises large and fair over the eastward lying hills beyond the bay. There is a path of silver across the water. The shadows of the great trees lie heavy on the grass. The lights in the cottages down at Old Mission Beach Resort begin to go out one by one.

It is time for home going. The good horses are rested and ready for home. Once more their hoof beats ring on the hard, level road.

Down the center of Peninsula this time. Right along the high ridge that is the “backbone,” in the old settlers’ dialect. On either side are deep ravines, dark with shadows. Overhead the trees shake shadowy hands with each other from either side of the way. The farm houses are all dark. The world is dead with silence but for the echoing hoof beats. On and on. At last we rush down a long winding hill road, and out on the level lowlands. To the right, the country with its fields. To the left the beautiful bay sparkling with silver in the moonlight. We are tired of saying “How beautiful!” but are silent and drink in the still loveliness of the moonlit water, the quiet fields, and the shadowy woods.

Another hour, and we cross again to the other side. The West Bay welcomes us with its wind-tossed waves. The village with its white houses stands still and fair under the oaks in the moonlight. It is its silent streets that echo with our horses’ hoof beats now. Forty miles and more of riding between supper and sleep, and such a ride!

Home at last!

——————————————————————————-

Notes: M.E. C. (Martha E. Cram Bates) Bates was an important literary figure of the Traverse area, arriving here in 1862. She married Thomas T. Bates, the editor of the Grand Traverse Herald, working in various capacities for that newspaper over the next thirty years. She especially enjoyed keeping a column in the Herald called “The Sunshine Society”, which entertained children with poems and stories. As an early woman journalist, she helped to found the Michigan Woman’s Press Association in the 1890’s.

Martha Bates was co-author (with Mary K. Buck) of two books, Along Traverse Shores (copies are available at Traverse Area District Library) and A Few Verses for a Few Friends. The present article is taken from the first volume. M.E.C. Bates died in 1905.