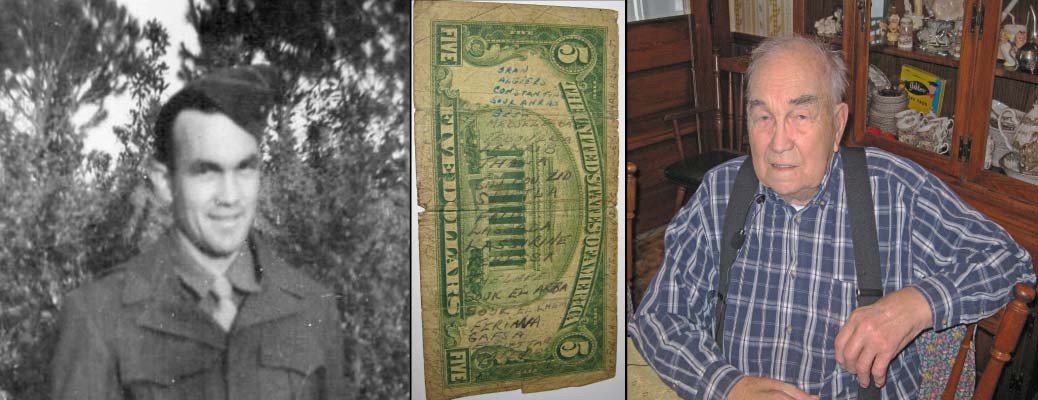

John Conroy’s story as related in interviews with Peter Newell, February 2015

This month’s “Celebrate the People” honors John Conroy, US Army 1st Armored Division and longtime resident of the village of Kingsley. Conroy’s reminiscences focus on his years of service in World War II. Few of those who served remain to tell their stories; 2015 marks the 70th anniversary of the end of that conflict.

While Grand Traverse Journal typically features stories concerning our local region, we recognize the importance of recording and publishing the stories of our residents, both for future generations and for the catharsis it gives those who have served.

WWII ended almost 70 years ago, so I don’t remember most of the bad stuff, but I will tell you all that I can. General Robinette’s strategies, as reported in Old Ironsides, the battle history of the 1st Armored by George F. Howe, and assignments were at the center of coming critical battles. I was proud to serve as a sergeant in Combat Command B under his command. When he was a colonel, he often rode in my command tank on short reconnaissance missions. Young officers were lucky to serve under our experienced commander early in the war. Lieutenants like mine were being cycled through different detachments for field experience. Most had had only 90 days training as officers and were brave with hopes of glory, but were brand new to North Africa.

The Germans were about to teach all our ranks hard lessons. We had only been in battle a little more than 9 weeks, while the North African Panzer division that we would soon face had years of battle experience. Their tank armor could pierce anything we had. We were only just receiving 75mm armor piercing to replace our training shells. Only a few of us had ever worked armor in terrain that had mountains, valleys, and desert plains. Good roads with major junctions crucial to military success were formed by many impassable wadis, rivers, and soft soil. When it was dry, dusty clouds gave away troop and armored movements which was good for my reconnaissance missions and bad for infantry. Terrain knowledge, battle experience, leaders, armor, and especially armor piercing ammunition led us to terrible losses through February 1942.

After our landing near Oran, Algeria in November 1942, the following January and February 1943 held dark days for us. Faid and Kasserine Passes were two important gateways through Tunisia and would fall to the Germans. We had fought our way east into southern Tunisia only to face Germany’s best desert division, Rommel’s 21st Panzer Division. Before those important battles, my lieutenant, with only 90 days training, commanding mine and two other light tanks, was sent to assist a small engineering troop that was repairing a bridge near Sbeitla. My rank as staff sergeant gave me no inside information to Gen. Robinette’s plans, but repair to a strategic bridge at Sbeitla made perfect sense. It is a small village halfway between the mountain passes at Faid and Kasserine. The repair of the bridge had to be strong enough to support our heavy armor that had to cross a small river bed that was more swamp than a flowing stream, called a wadi. What happened during a little skirmish was only the beginning of a series of disappointments and made me question my own value as a soldier.

As we approached the wadi, we saw a German Tiger Tank of the 21st Panzer Division, the most feared tank in North Africa, and what looked like a full platoon of German infantry on the opposite side, which gave them about 10 to 1 odds against us. Information of Panzer movement was important to our command, but our immediate concern was the tank armed with a 75 mm cannon. While an 88mm cannon was more powerful and would pass clear through even our heaviest tank, the 75mm would pass through one armored side then rattle around and do worse damage to everything and everyone inside.

My lieutenant was quick to order two of our light tanks straight ahead toward the Germans and closer to the wadi and then attempted to turn around in the soft sand on the side of the narrow road. Seconds later, they were both bottomed out, off the road, and stuck. His command of the situation disintegrated. With more courage than sense, the lieutenant ordered his command tank to fire two 37mm shots at the German Tiger Tank, even though neither shot had a chance of penetrating the front armor of a Tiger tank. To this day, I thank God that the German tank never returned fire.

I asked the lieutenant “Do you want me to put the grousers on the stuck vehicles?”

Grousers would improve the traction of rubber cleats in soft sandy conditions.

His next order completely baffled me and my driver as he looked at us, he said, “No. Just get the hell out of here.”

I have never before or since received an order like that. The other lieutenant also ordered two of his engineers to leave with us. Then, both lieutenants left with the rest of our men and went toward the wadi before flanking left into old and scrubby olive trees that reached a couple feet higher than our light tanks. That was last I saw of 12 lightly armed men and two lieutenants, most of whom I knew. Same outfit, same platoon, you get to know all the guys one way or another.

Instead of running away immediately, I disobeyed a direct order. I and my men waited for some sign of those who had just left. Nothing. Complete silence. We waited, watching and listening for footsteps, crackling brush, shouts, gunfire, anything. A few minutes later Germans begin to appear on our side of the wadi directly from the direction that our people had disappeared. With the enemy now flanking us, we were learning, first hand, how good the Germans were at warfare. We hit the ditch on the left side of the road and followed it toward a nearby mountain about ¾ mile away. It lay in the general direction that led back to bivouac, and had the best cover for escape. It would add days of walking, but the other options were open road or open desert. With only rocks and sand for cover, and about 30 minutes to clear the area before being captured, I chose the longer route. I figured if our buddies were still alive, we would make contact with them, because they were somewhere in the same cover we were in. 30 minutes later, we found no joy in making it safely through the undergrowth to the base of the mountain. There was no sign of our friends. Twelve good men and two lieutenants with more courage than sense were missing, and I knew that, at best, they had been captured. I never saw them again.

I had rank on the three men who followed me, so I was the one most responsible to get us all back to bivouac alive. January nights get cold in the Central Tunisian desert, so we were grateful to find a stack of straw to burrow into for the night. We needed rest to continue our march that could take days with limited rations. There are no straight roads in the mountains, so an hour’s travel by tank on flat ground would take us nearly three days hiking. No rank below lieutenant was given maps for fear of being captured with explicit information, so I had to guide us by point to point navigation, the same as I used growing up in rural Kingsley, Michigan.

On the second day of our march, we were still on the mountain, skirting a flat open area, when my driver spotted two men walking in nearly the opposite direction of our path. As they drew closer, we could see that they wore American uniforms. One was a ranking officer, colonel or major, accompanied by a private. I talked with him a little bit about our situation.

The officer said, “ I can’t see sending my troops into the mess that you have left just to get my men killed.”

He looked dead serious however impossible his thinking was.

I thought, “Here is this officer and a private on the flat open area of a mountain taking a Sunday walk.”

I didn’t see any of his troops, nor would he give me any more information about why they were there. He didn’t say how long he had been walking or the circumstances that got him isolated from his command. It sounded like he had pretty much lost his mind. They didn’t want to join us in getting back. It was the craziest thing I had ever seen, and I couldn’t figure out what to do with them. I didn’t have rank to countermand any real or imagined mission he had. We went on our own way. They went theirs and we never saw them again. On the third day, we found a unit of American 105mm artillery and caught a ride with them back to bivouac.

My First Armored division had darker days ahead at Kasserine and Faid Passes. At Kasserine Pass, I was part of a reconnaissance unit that watched from the heights of a nearby mountain while Combat Command C suffered huge losses. They didn’t have anything for protection in open desert caught between two mountains with deadly German artillery concealed in rugged slopes over a mile away, but that is another story. And another story is about being pinned down at Anzio more than four months, where winning the war became more remote and less important than surviving each day.

I knew Uncle John was in the war but didn’t know what he did. This is a great article about a great man. Thanks for sharing.

Mark Mox, son of Ken and Mildred Mox of Kingsley

Thanks, Mark! I know John and Pete Newell got to know each other pretty well while getting this all down. Some memories are hard to get over… a good ear does a lot for the soul, Pete will tell you! Thanks for reading and commenting!