Your Editors at Grand Traverse Journal look forward to publications of local interest, and 2015 has kicked off with a winner in Dr. Stacy Leroy Daniels’ The Comedy of Crystal Lake.

The Comedy of Crystal Lake is the type of regional history we long to read, filled with descriptions of true characters that cultivated our immediate surroundings. Perhaps you too have driven through the quaint village of Beulah and wondered, “Who is Archibald Jones, and why does he deserve his own day?” Or, having read the 1922 account of The Tragedy of Crystal Lake, you were left saying, “If you ask me, it’s the present asking prices of homes on the shore that are the tragedy, not the rapid lowering of the lake level way back when.”

This tome answers a number of these questions and curiosities of life on Crystal Lake, and to our joy, Daniels’ robust scholarship more than stands up to scrutiny. Within, you will find a number of contemporary accounts that introduce you thoroughly to the people and their thoughts in 1870s Benzie County, as well as historical records, some of which were found hilariously serendipitously! Your Editors would reveal more, but instead, we encourage your patronage of local authors of history: Pick up your copy today! ~Amy Barritt, co-Editor

Dr. Stacy Leroy Daniels presented the following summary of his work to Grand Traverse Journal, at the request of Your Editors. Information on purchasing your own copy is found at the end:

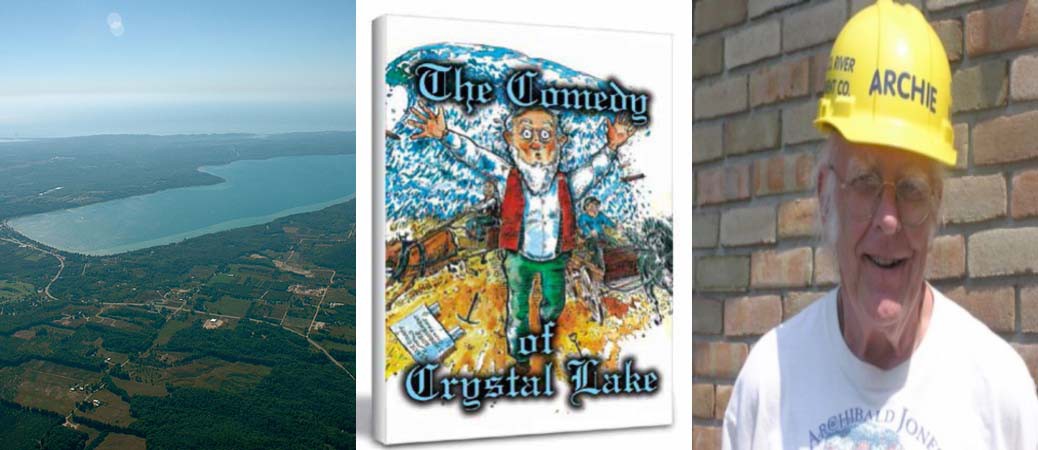

Shortly after settlement in the 1850s, Michigan’s peculiar travel needs were apparent: to improve the land-locked entrances of drowned river mouths along the eastern shoreline of Lake Michigan by creating “harbors of refuge” for shipping, and inland waterways to access the interior of the State. Many natural river outlets were straightened and new channels dredged to navigable depths to connect nearby inland lakes by “slack-water” canals to Lake Michigan. These included: Saugatuck, Holland, Grand Haven, Muskegon, White Lake, Pentwater, Ludington, Manistee, Portage, Frankfort, Charlevoix, and Petoskey. The attempt to connect a canal from Frankfort Harbor to Crystal Lake proved to be the most ambitious of its kind.

Published earlier this year, The Comedy of Crystal Lake, by Dr. Stacy Leroy Daniels, details the real-life drama of the lowering of Crystal Lake (Benzie County), which resulted from an attempt to build a slack-water canal to nearby Lake Michigan. It is a sequel to “The Tragedy of Crystal Lake”, a classic pamphlet by William L. Case (1922).*

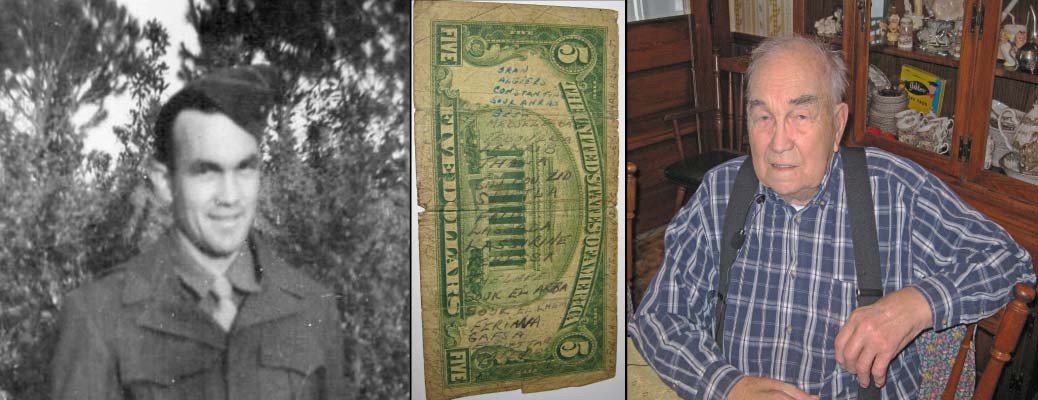

Daniels covers this part of Benzie County history with a focus on Archibald Jones, “the man who (allegedly) pulled the plug at Crystal Lake.” Jones founded the Benzie County River Improvement Company in 1873, to improve waterlots on Crystal Lake, remove obstructions and construct slack-water canals between Crystal Lake and Lake Michigan, and build a steamboat to facilitate shipping of settlers and goods to and from the interior of the County to the nearby port of Frankfort.

By Jones’ maneuverings, the level of Crystal Lake was dramatically lowered in an attempt to construct a slack-water canal between it and Lake Michigan in 1873. Most other canals had differences in level of only a few feet; The original level of Crystal Lake was 38 feet above Lake Michigan which made it especially attractive for a canal. Unfortunately, the whitecap waves of Crystal Lake washed out a temporary dam before a permanent canal could be completed. The level of the Lake dropped precipitously by 20 feet and 76 billion gallons of water poured down its outlet.

Although a canal system was never realized, the lowering of the Lake exposed a 21-mile perimeter of sandy beach where none had previously existed. This made possible: the founding of the Village of Beulah, the coming of the railroad, installation of telegraph and telephone lines, development of lakeside resorts, construction of 1,100 cottages, all connected by an infrastructure of perimeter roads and trails.

Such is the “Comedy” of Crystal Lake – an epochal event with unintended consequences which has evolved from perceived “failure” of an “ill-conceived” project by an apparent scapegoat, to unqualified “success” by a visionary celebrated as a local hero!

Copies are available for purchase at BaySide Printing, Frankfort; The Bookstore, Frankfort; Cottage Book Shop, Glen Arbor; Horizon Books, Traverse City; Benzie Conservation District; Benzie Area Historical Museum; Benzie County Chamber of Commerce; Frankfort-Elberta Chamber of Commerce; partial proceeds to local nonprofit organizations.

You may also purchase copies direct from Flushed With Pride Press, PO Box 281; Frankfort, MI 49635; 989-750-2653; flushedwithpridepress@gmail.com. 496 pages; 46 chapters; 16 appendices, 200 illustrations, maps, timelines, & sidelights. $49.95 + $3.00 sales tax (+ $10.00 shipping and handling if mailed).

Dr. Stacy L. Daniels (PhD, UM 1967), has been a practicing environmental engineer in industry (Dow Chemical Co.), academia (University of Michigan), small business (Ingenuity IEQ, Inc.), governmental agencies, and nonprofit organizations (Crystal Lake & Watershed Association, CLWA) since the 1960’s. He has observed, participated, and directed many studies of Crystal Lake and its Watershed, and has published a new book, “The Comedy of Crystal Lake (2015). His activities with the CLWA have included: chair of the Education & Communications Committee, editor for the newsletter and webpage, and coordinator for the Crystal Lake “Walkabout”. He has been a member or chair of several national science advisory committees, and has authored/coauthored over 300 papers and presentations. He runs the Crystal Lake Team Marathon, enjoys reading history, and writing serious (and humorous) environmental poetry.

*Several editions of “The Tragedy of Crystal Lake,” by William L. Case, as well as copies of “The Comedy of Crystal Lake,” by Dr. Stacy Leroy Daniels are available for circulation at Traverse Area District Library, Benzie Shores District Library and Benzonia Public Library.

Header image of Crystal Lake courtesy of Delta Whiskey, https://flic.kr/p/9AgJme