In the early years of the twentieth century rural students attended one-room schools from kindergarten through eighth grade. A single classroom teacher would teach as many as forty-five children beginning in September and extending until May or June, with only a few weeks of vacation at Christmas, spring break, and a few holidays such as Christmas and New Years. Through the 1950’s such schools continued to educate children in this manner, and many persons remember them to this day, often with fond recollections of their school days. Only after the passage of legislation to consolidate rural schools in 1965 did they disappear in Michigan—as they did nearly simultaneously elsewhere (with exceptions for isolated communities). Now, as memorials to the past, they grace the countryside as unoccupied or transformed buildings, each with a school bell tower presiding over an abandoned schoolyard.

As a former secondary teacher, I became fascinated with the education conducted in one-room schools. If I felt overwhelmed preparing lessons for five classes of 14-15 year-olds every day with only two different preparations, then how could a single teacher prepare lessons for eight different grades (plus kindergarten) for as many as six different subjects? What magic would she–the feminine pronoun is intended since most primary teachers were young women–work to keep such a diverse group of children on task for six hours of instructional time every day? Can modern teachers learn something from practices long abandoned and nearly forgotten? I resolved to find out.

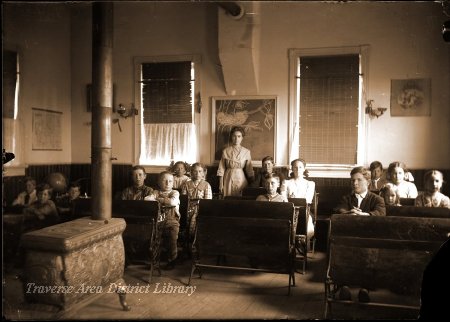

I identified sources that would help me learn about one-room schools. One of them–oral histories of both students and teachers preserved online–provided glimpses into the way distant memories were recorded and remembered today. Students would remember the pot-bellied stove, the ringing of the school bell, the outhouses, the games played at recess, patriotic pictures that adorned the walls, and the teacher’s manner of dealing with students. Teachers remembered starting the fire early in the morning, walking or riding to school on wintry days, the clean-up chores at the end of the day, and interactions with individual students. Both groups felt a strong sense of belongingness, solidarity, a family-like atmosphere inside the classroom. Older students would help younger ones, and the teacher as well when it came to doing school chores. Certainly there were exceptions—it was not a perfect family after all, but in general, it worked: children received an education and the teacher administered the process.

What kind of education was it these children—our grandparents and great-grandparents—received? In one-room schoolhouses, students were busy doing two things when they were not enjoying an hour’s lunch and two recesses, morning and afternoon: they studied at their desks or they were called forward to recite. Recitation has a peculiar meaning in school jargon: it is not simply reciting something memorized (such as a poem), but has to do more with demonstrating proficiency in a task given by the teacher. Recitations could involve reciting a poem, but more often they were about reading aloud, answering questions posed by the teacher or the textbook, working arithmetic problems, displaying an example of good penmanship, or copying out a list of state capitols from a geography book. Study time was just that: the time spent between recitations in reading, working arithmetic problems, answering questions based on written passages, or practicing penmanship. Classrooms, while not stony silent, were relatively quiet places with the teacher up front with a group that was doing their recitations, while the rest of the class engaged in the tasks laid out for them.

For the most part, those tasks depended on written passages in textbook readers as well as problems and drills given in arithmetic texts, one for each level. Some schools were divided up into eight separate grades, a nightmare of organization for the teacher who had to keep each child busy during study time. Other classes had three levels, beginners, middle, and high level, the highest being for older students who were preparing the eighth grade graduation examination that was required as a salutary end to one’s schooling or else for entry into high school. For a time the eighth grade tests were written by officials at the county level, but later they came from the State Department of Education in Lansing. By today’s standards, they were not easy. Readers will find a comparison of modern and early eighth grade tests here.

How were recitations scheduled during the school day? Albert Salisbury in his 1911 book School Management proposes 22 of them covering all subjects, each lasting ten minutes. Beginners receive more recitations than older students because of the urgency of getting them up to speed in reading. The most difficult subjects come early in the day when the mind is fresh, the less demanding ones later in the afternoon. A regular tide-like alternation of recitation and study was preferred to create a sense of order. So it was that groups of students circulated in the classroom, often in response to a verbal or nonverbal cue to call children up to the front for recitation. It is a wonder that the system worked with such precision and military-like discipline. Sometimes, no doubt, it did not.

Another source of information about teaching and learning in one-room schools comes from teacher grade books. I have looked at two of them from Kingsley, Michigan, one recording student attendance and achievement between 1894 and 1902, and another containing records from 1908 to 1912. In each of them, the elegant handwriting of several teachers tells of pupils’ names, ages, deportment (behavior), and attendance over the course of the year, sometimes giving the reasons for absence. The later one gives the grade levels of each student as well as her/his academic achievement in each subject, presented through monthly grades. Teacher recommendations about promotion to the next grade are recorded in the last entry for the spring term. These registers provide a rare glimpse into education conducted in one-room schools at the turn of the century.

Examining them carefully, several facts stand out from the outset: students vary in age from 5 to as old as 18; age is not always connected to grade level as it is nowadays—a thirteen-year old can be working at a fifth or sixth grade level, for example; class sizes vary both from year to year and by time of the year; attendance can be erratic with some students missing many days over the course of the year. With regard to the last point, October and the spring months had the most absences—perhaps because of harvest in the fall and planting duties in the spring. Some students—especially those 14 and older–tended to leave school in April and May, sometimes never to return. No doubt they were working, or else had given up on their plan to finish eighth grade. At a time when work was plentiful for those who had not finished primary school, quitting school was a reasonable decision.

Academic information is not given in the traditional A-F format, but is displayed as monthly scores for each subject. In general, they indicate fair to high achievement; it is nearly impossible to find scores less than 70. Younger children—five and six years old—are given assessments through descriptions: “excellent,” “very good,” or “good.” When deportment is noted in the registers, it is described similarly: it is very difficult to find deportment grades less than “good”—most were “excellent.” Evidently, teachers were satisfied with the behavior of their students, though an occasional comment such as “Moved away—much to the relief of all” indicates that the children were not all perfect in deportment.

Other comments shine a light on what life in a one-room school was like at this time in our history: “Very bright and faithful student.” “Exceptionally bright but irregular in attendance because of lameness.” “Very slow to learn or do anything else.” “A downright bad girl.” “Quarantined –typhoid fever.” “Has St. Vitus dance.” “This boy was 16 years old the day school opened. He does not need to go to school anymore.” “Will not come in cold weather—has to walk 3 ½ miles.” The diversity of pupils stands out from this selection of comments.

What was taught in one-room schools? For one thing, the curriculum depended on the age of the student—younger ones concentrating on the usual Reading, Spelling, Writing, and Arithmetic—with older ones adding Geography, Grammar, and Physiology to that list. Physiology was not just about the human body: it discussed various topics relating to health, especially focusing on abstinence from alcohol, tobacco, and drugs. Students preparing for the eighth grade examinations knew they would be tested on these subjects, and spent study time in class reading from appropriate textbooks. Their success on the examinations would be great source of pride for them and their parents. In some schools, there were graduation ceremonies from eighth grade that underlined the importance of finishing primary school.

From a modern point of view, it is impossible to deny the advantages of one-room schools, just as it is impossible to deny their shortcomings. Above all, school is a social enterprise: it informs children as to what things count the most in society, reinforces the socializing influences of the family, and teaches right and wrong. Moral education, while sounding quaint in modern parlance, underlines the role of the school in this regard. Even now, while often unexpressed in mission statements, it is seen as an important—some would say the most important function of schools. For many citizens, it may overshadow the expressed mission of schools–which often has to with academic achievement.

Based upon the memories of those who experienced it, one-room schooling was extraordinarily successful in children’s moral education. Former students remember older students helping younger ones, the strict rules laid down for conduct, the sharing of resources when resources were scarce, the fun times during recess and holiday celebrations, the strong arms of older boys in loading a potbelly stove that kept the room warm in winter. The classroom was a family, not always perfect in conduct or in effort, but a family nevertheless, a body of individuals that cared about each other. By contrast, modern elementary schools consist of a body of students brought by school buses to a location not necessarily close to where children live. Parental contact is limited to occasional parent-teacher conferences, email exchanges, and rare phone calls. Teachers do not know families in the same manner they did a hundred years ago.

This is not to say that one-room schooling is a good model for education. A hundred years ago, academic training was largely built upon memorization and the mastery of skills. Now we know that children can do more than write neatly, learn to spell correctly, read textbooks, and do arithmetic problems that do not require understanding of mathematical principles. By eighth grade we ask students to answer questions inquiring about the evidence used to back up an argument, demonstrate the scientific method, and work math problems that go beyond rote performance of skills such as long division. Schoolwork is not easier than it used to be—in some ways more demands are placed on young people. Memorizing lists of spelling words during class time is an easier task than identifying the theme of a written passage.

One-room schooling placed inordinate demands on teachers. Few of them stayed in a position for longer than two or three years. Not only was the salary inadequate, but the work demanded a commitment to the job few people are able to give. Relying on young, bright women to staff schools between their high school graduation and marriage was a practice that could not be sustained. As soon as other jobs opened up for them, they took them, leaving the low salaries, lack of respect, and overwork behind. In part, the era of one-room schooling ended because of this change in values in society.

Still, we think of the one-room school as a delightful artifact of a bygone age. We imagine it reflected values that underlie a fair and decent society–caring for the young, fostering independence, sharing resources, accepting discipline, and mastering reading, writing, and arithmetic. Indeed, in some ways it did, but at a cost of students filling countless hours with exercises in drudgery. Harried teachers as young as eighteen or twenty rarely reached the high standards demanded today—a few months in normal school would qualify them to teach. Shoddy buildings and poorly designed instructional materials were hardly sufficient for a fine education. No provision was made for students that were different—physically, mentally, or emotionally. Attendance could be sporadic due to the weather, work required at the farm, disinterest in studies, illness and disability. The United States left one-room schools behind for good reason: they failed to satisfy the need of society for better-educated young people. We should look upon them as but one step along a pathway that leads to a well-educated citizenry, a pathway we are still following.