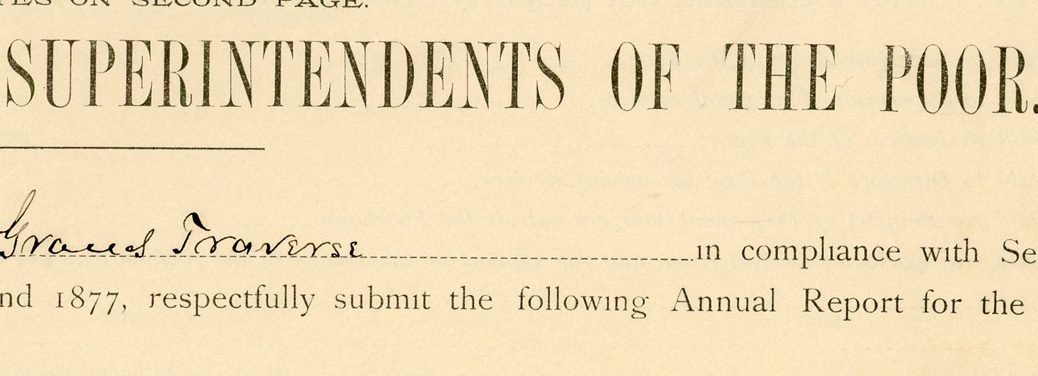

Before the government social services we know today (Social Security, food stamps, unemployment insurance, etc.), how did we care for people in our society in need? Using the terminology of early reports that recently surfaced at the Traverse Area District Library’s local history collection–how did we care for “paupers” and the “indigent”? These reports, annually filed by Grand Traverse County with the state of Michigan, date from 1885, 1886, and 1891.

The records are scant, but interesting, and would merit further study using nationwide statistics. But, for our purposes, we’ll present the reports as they are, whether or not we can draw definite conclusions about them. (1)

Two unidentified adults of Irish nationality, a man and a woman, were the sole “paupers” maintained in the Grand Traverse County Poorhouse in 1885 (and 30 other people were assisted in other institutions and in their homes). Other than where they hailed from, we know nothing about them, but get this: Under the reporting section for “Food,” the Superintendents said: “No regular routine has been adopted, but the usual food found upon the table of a good wholesome farm table.” A regular routine for feeding I think would be beneficial, but at least it was all “wholesome” (as a nation, we wouldn’t start counting calories regularly until Lulu Hunt Peters, whose 1918 book on diet, exercise, and health, promised all women they could get their ideal body image through counting. “Thin is in!”)

How wholesome was the food? We don’t know what was served, but of the $1,981.51 spent on the care of persons in the poorhouse, a whopping $1,489.87 was spent on food alone. DANG, that’s a chunk of budget! But was it enough? Considering a $460 yearly income for a family of five was considered just out of poverty, spending that much on 32 people for a year seems adequate, each being fed on about $43 a year (especially since most only received a little assistance for part of the year).(2)

What did care look like? The reports provide little detail, but they did differentiate between the costs of care provided to those living at the poorhouse and the costs associated with people living on their own, but requiring some extra assistance. Deaths or illness in a family were common reasons people living on their own sought help.

For both groups, there are expense lines for staff, medical services, funerals, food, fuel, clothing, necessary supplies, furniture, hired labor, purchasing land for a poor farm, erecting new buildings, supplies for said farm, and paid transportation. The reports written by the superintendents are short and to the point. Under “Facilities for Bathing,” a category describing the poorhouse, the answer was “Not any.” Not even a jug in the corner? Harsh.

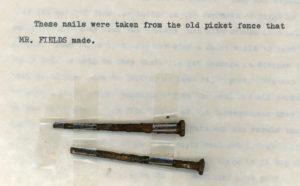

“What is that about a poor farm?,” you say? Indeed, farmland was purchased by the County in 1885 to operate a farm, with the resulting food stuffs either being consumed by the residents, or sold at fair market value. We don’t know if a profit was ever made, as those lines on the reports are blank all three years. The initial cost of the land was $300, acreage unspecified.

The population in 1886 was much more diverse than 1885, with seven people: three Americans, one English, one German, one French, one Swedish, one Canadian/Scotch, and one “Mulatto.” The Report makes it clear, the State wanted a count of “All in whom there appears a mixture of White and Negro,” whether that was self-reported or not, we will never know. You could also have been Indian, or, if one qualified and wished to be more specific, Half-breed, by the State’s reckoning. Yikes.

A similar mix occupied the poorhouse in 1891. In that year, the total amount spent by Grand Traverse County on the care and support of the residents was $2,994.62, about half of which was spent on maintaining the poorhouse and farm ($851.76) and the salary of the poorhouse keeper ($645.60). Only $112.75 was spent on food, so here’s hoping the poor farm was producing some supplemental vittles!

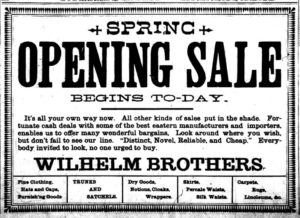

Grand Traverse County was not the only provider in the area, either: Traverse City also provided for the poor in its jurisdiction, as far back as 1898. They may have been offering services prior to that year, but unfortunately we do not have the City Annual Reports dating earlier. Also, 1885 is the year the Traverse City State Hospital (then known as the Northern Michigan Asylum) opened its doors to its first 43 residents, and there is every real chance some of the locals that were formerly on the “poor rolls” were committed there. We also have newspaper articles advertising various fundraising events by a number of civic-minded groups and individuals, raising funds for the care of people in need. So, care for those in need was considered a “group effort” in young Grand Traverse County.

More information on the poorhouse and its operations can be found in the “Proceedings of the Grand Traverse County Board of Supervisors, Reports of County Officers and Official Canvass,” the oldest volume of which Traverse Area District Library has is 1904. That particular volume contains a number of interesting facts about medical care to the poor. At the meeting of April 12th, the name of Dr. August L. Rosenthal Thompson pops up, one of our favorite women of young Traverse City (Thompson appears briefly in the tales of our other early female physician, Sara T. Chase-Wilson.) Thompson visited Maude and James Wheeler of 428 Garfield Avenue, who suffered from Scarlet Fever and pseudo-diptheria a total of 44 times, charging the poorhouse $1 for each visit, and $3 for medicine, a total bill of $47.

Dr. Holliday also presented a bill at the same meeting, which was at first disputed by the poorhouse supervisors, but ultimately paid in full. Perhaps in response to some ill-treatment (pun intended) Holliday had felt from that event, he and many other doctors, including Rosenthal-Thompson, submitted a “recommended” plan on October 17th: that the Board of Supervisors should take responsibility for decisions made by county employees under their direct supervision, and that, when they hire a doctor, they would ensure the service “would be paid for at a rate based upon either the usual rates charged by reputable physicians, or, if the body deemed advisable, upon a basis of a fixed tariff of rates compiled by and agreed up, by a joint committee representing your honorable body and the physicians of said county.” Holliday, et. al., must’ve felt quite put-out, or, as the kids today would say, “Bitter much, Doc?”

As another scholar in the field observed, responsibility for the poor in our community fell first to the family.(3) Only if the hardships were beyond the scope of the family, or in the case of tramps, there was likely no family at all, is when the state and local government would step in and provide care. Despite the apparent racism and classism built in to the reporting, overall it appears Grand Traverse County did at least and adequate job to help those in need in the 1880s.

Amy Barritt is co-editor of Grand Traverse Journal. For more on Traverse City’s work with the poor, check out Richard Fidler’s Who We Were, What We Did.

(1) A brief digression: Let’s talk about the mindset of the persons providing the care to those who needed it. The nineteenth century was rife with doctors and do-gooders who saw the flaws in humanity as a product of moral failing (read more on this school of thought in the words of Dorothea Dix and other social reformers). In these reports, the handwritten notes indicate that there are people considered “deserving poor,” who were not held responsible for their lot in life, such as the deaf and disabled, the aged, etc. Then, there are the “paupers,” which included tramps, hobos, and other persons that were seen as “unwilling to work.”

(2) Hunter, Robert. Poverty. London: The Macmillan Company, 1904.

(3) Fidler, Richard. Who We Were, What We Did. Traverse City: Traverse Area Historical Society, 2009.