For as long as there have been automobiles, there have been gas stations. At first they were no more than pumps along curbs, but, as oil companies began to compete for market share, they took on a specific character that proclaimed service, style, and branding to the motorist and to the public in general. That character was expressed in station design and the way gas stations fit into neighborhoods and communities. Even now, in subtle ways, they communicate a sense of product and place to all people, not just auto owners.

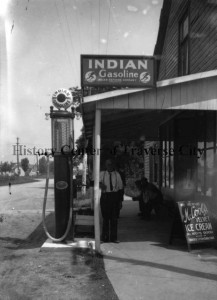

In the Grand Traverse area it is impossible to find curbside gas pumps, since regulations concerning the dispensing of gasoline products forbid them. In the first and second decades of the twentieth century, however, they were common. The picture below showing the “Indian Gasoline” station in Elk Rapids is typical of the curbside design. At this early time little effort was expended to mark a gas station as a place designed to fill a specific function: only the branding on the pumps, “Indian Gasoline,” tells us anything about the product.

In the 1920’s, gas stations began to take on a new appearance. One new design was the house filling station, one of which still exists in Traverse City as the “Flower Station” on West Front Street. As cars became more prevalent, oil companies sought lots close to residential neighborhoods in order to market their products to homeowners who drove automobiles. Since they had to blend in with nearby homes, such stations frequently sported a steeply inclined roof, windows with individual panes, flower boxes, even chimneys. Such places certainly did not convey the reality of exhaust fumes, the smell of gasoline, and the sounds of automobile engines—all of that would clash with the quiet elegance of nearby homes.

The next major innovation in gas station design was the oblong box, a rectangular design with individual bays for servicing. During the 1930’s oil companies expanded product lines such as batteries, tires, and other accessories. Crandall’s iconic station at the corner of Union and Eighth Street (now Randy’s Service) clearly labels each of the bays: washing, greasing, batteries, and tires. Its handsome art deco appearance has drawn attention from many architectural preservationists. Cliff’s Service on Union Street near 14th across from Speedway is a smaller version of this style. The “oblong box” prevailed from 1940 until 1980 as the dominant design for gas stations.

Beginning about 1970, a new style evolved: the small box. Emphasizing low prices, retailers presented their product in no-nonsense fashion, selling nothing but gas, oil, and a small amount of merchandise aimed at the motoring public. Clark Oil and independents avoided all kinds of promotional gimmicks in order to undercut prices of the major companies, Shell, Mobil, Texaco, Phillips, and the rest. In Traverse City there remain two such stations, one on Division Street and the other on East Front. The latter location is still in operation, though it has added a canopy.

About the same time as the small box, the Canopy and Booth design was created—and for the same reason. Here, the small box has been reduced to a building no bigger than a highway toll booth. Often a canopy was added to protect customers from the elements. Rest rooms and vending areas occupied small shed-like structures at either end of pump island. In the Traverse area, two of them remain, both active—one on US 31 South, a few miles out of town, and another on East Front west of Garfield Avenue.

Finally, the most modern incarnation of the gas station is the Convenience Store with Canopy, a design that has become increasingly popular since 1990. Gone is the joining of auto service to the retail purchase of gasoline. In fact, gasoline is only one of many products motorists and shoppers can purchase: cigarettes, fast food, beer, and lottery tickets make up a large percentage of sales, though oil, windshield washer fluid, car washes, and even air for tires are sold, too. Pumps are untended, the consumer required to pump his/her own gas.

How the gas station has changed since the early days! Within the memories of those still living it has morphed from a neighborhood fixture emphasizing personal service to an impersonal store only slightly related to automobile travel. Where before uniformed attendants used to pump gas, check the oil, fill up tires, and maintain automobile systems, now motorists can fill up without even entering the business, paying with a credit card after a few minutes spent at the pump. In such an experience, the human element has been eliminated entirely.

The rubber hoses spread on the drive that cheerfully announced the arrival of a new customer with a cheerful “ding,” are forever gone, their absence lamented by those who can remember when getting a fill-up meant more than a simple transaction for gas. Like the neighborhood grocer, the local gas station owner no longer interacts with us, that job being sacrificed in the name of efficiency and lower prices. It has not been a completely satisfactory trade-off.

The book most useful in preparing this article was The Gas Station in America, by John A. Jakle and Keith A. Sculle. It was obtained by means of interlibrary loan through the Traverse Area District Library.

Richard Fidler is co-editor of Grand Traverse Journal.

For more information on interlibrary loan services offered by Traverse Area District Library, please visit the following page: http://www.tadl.org/melcat-interlibrary-loan