by S.A. McFerran, B.A. Environmental Studies, Antioch University

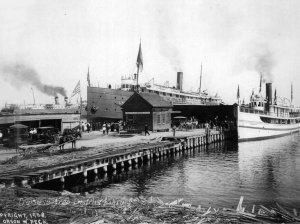

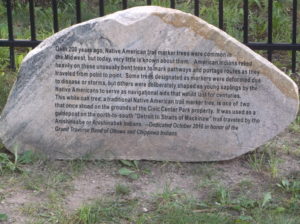

A new group recently met at Fishtown in Leland to initiate the Fisheries Heritage Trail. The trail will link historic fishing villages throughout the Great Lakes. It will provide access to historic archives relating to commercial fishing as well as the sites occupied by shoreline communities where fishers lived. The effort is sponsored by Sea Grant, Michigan Maritime Museum, the Pokey Huddle Institute and NOAA Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary and others.

Fresh Great Lakes fish bought in the market are caught by commercial fishers, sports fishers are not allowed to sell fish they catch by hook and line. Commercial fishing operations still use classic high deck tugs that can protect the crew from the weather all year round. The tug I worked on had a coal stove that really kicked out the heat. Trap net commercial operations use vessels with low decks and generally only fish in good weather.

It was decreed with consent that the sports/commercial fishing divide would be defined by kinds of fish caught as well as fishing methods. Commercial fishers catch coregonids, whitefish, chubs, cisco and herring. These native fish of the genus coregonus live in all parts of Great Lakes waters and throughout colder regions of the globe. Sports fishers catch large predator fish that are raised in hatcheries and have biometric tags inserted in their heads as they are released.

As the 20 year period of the consent decree approaches the end, it is apparent that the fisheries resources pie has changed since 2000. While some species have declined others have increased such as walleye in the Saginaw bay. Many feel it would be appropriate to allow commercial walleye fishing in the Saginaw Bay. Randall Claramunt of the DNR has recently talked about “paradigm shift” due to changing fish populations. 1.

The catch of native whitefish (coegonus cupaliformis) in Lake Michigan and Huron is still substantial, 2.2 million pounds in 2015. The trap nets whitefish are caught in stand on the bottom of the lake in shallow areas and are pulled up and checked for fish. The tugs set gill nets that can stand at depths of hundreds of feet.

Aquaculture in Michigan is in service of sportsmen. Sportsfishermen are fishing harder with their hooks and lines for the non-native game fish raised in State of Michigan Hatcheries. The State government has a firm hold on aquaculture and an enthusiastic constituency of sportsmen. As the ecosystem changes and the “consent decree” expires it is time to rethink how fisheries in Michigan are managed. With an eye to history, thoughtful decisions can be made with the consent of stake holders. Many who buy fresh Great Lakes fish in the market recognize the efforts of commercial fishers. Efforts to expand aquaculture operations in Great Lakes waters are long over due.

The Great Lakes Fisheries Heritage Trail can provide perspective on how the fisheries resource has changed. The Consent Decree renegotiation is an opportunity to envision a new paradigm. Former commercial fishers and others knowledgeable in fisheries issues support the expansion of commercial fishing and aquaculture in the open waters of the Great Lakes. State governments have the expertise to manage such operations without interfering with sportsmen as they take their boat rides in fine weather.

1. “King salmon reign becomes more precarious on changing Great Lakes”; Keith Matheny, Detroit Free Press Published, Oct. 23, 2017

Stewart. A. McFerran teaches a class on the Natural History of Michigan Rivers at NMC and is a frequent contributor to the Grand Traverse Journal.