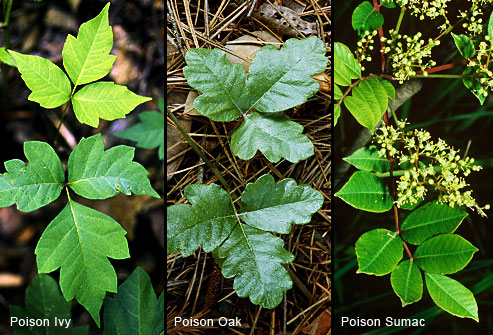

Poison ivy, poison sumac, poison oak: the three poisons we have to take care not to touch. The third doesn’t grow here, so we don’t need to worry about it. Somewhat rare in Northern Michigan, Poison sumac is a tall shrub that grows in wet places—I have seen it in the Platt River valley, locally. Ed Voss’s magnificent floral guide Michigan Flora shows a cluster of counties with the species: Benzie, Grand Traverse, Leelanau, and Antrim. It is much more common downstate.

Poison sumac will not be confused with other sumacs, the staghorn sumac, for example. That plant has red berries and grows along fields and edges of hardwoods. As a teacher, I sometimes had to quell students’ fears that they would break out from touching staghorn sumac. Unlike that familiar shrub, poison sumac grows in places where you get your feet wet. If it has berries at all, they are white. The leaves have the shiny look of poison ivy, but have 7-11 leaflets. Persons in search of pretty autumn color for their homes may be surprised to learn they brought it into the house.

Poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix) is closely related to an Asian plant (Toxicodendron vernicifluum) which is used to make lacquer in Japan and elsewhere in Asia. While serving in Japan, a dermatologist friend told me that patients came to him with a rash similar to that of poison ivy on the backs of their thighs. The cause turned out to be toilet seats covered with the offending lacquer.

Poison ivy grows in a variety of plant communities: sand dunes, banks, shores, and along roadsides and railroad tracks. In the north, it does not climb trees, but remains as a small shrub, scarcely growing taller than two feet. Its shiny green leaves are, indeed, in threes (“leaves of three, let them be”), but that characteristic is not at all helpful since strawberry leaves come in threes, too. In contrast to the shrub form, it frequently takes on the growth habit of a vine in Southern Michigan, climbing a variety of trees, often to great height. Manistee county, according to Voss, is the farthest north this variety is to be found.

Are two such radically different varieties—one a shrub and the other a vine—really the same species? In most characteristics—leaf position and shape, length of leaf stems, inflorescence (arrangement of flowers on the stem), number of flowers, fruit size—they are similar, but not identical. The vine form has aerial rootlets to cling onto tree trunks, while the shrub form has none. If they are the same species, they should form intermediate forms upon crossing the two. Have they been crossed to see what the offspring look like?

Unfortunately, my source—William T. Gillis’s article in the Michigan Botanist, Vol. 1, 1962—talks only about one failed attempt. An early frost killed the buds on the growing hybrids. Gillis did attempt to bring the northern rydbergii form to southern Michigan to see if they would begin to take on southern characteristics. They did not.

Let us leave the subject to say that poison ivy is a highly variable plant. One characteristic that all forms have is that they possess urushiol, the offending substance that causes the skin reaction in some persons. It is not volatile, so you cannot get the rash from merely standing close to plants: you must break the resin canals in the leaves in order to be exposed. Once exposed, it may take one or two days to react, or—in some cases—only a few hours, depending on the sensitivity of the person afflicted. Dogs and cats can carry the allergen on their fur, and smoke from burning leaves can cause serious trouble. It can even be carried on water—at least in the case of poison sumac, the species that loves to grow with roots in the water.

Not everyone is sensitive. Some persons can handle leaves and fruit with impunity. However, you cannot always count on previous insensitivity to avoid the rash. Sensitivity can change over time, and in either direction. Steroidal creams and lotions ease the suffering of those afflicted, and the itching and angry blisters will disappear over time. Still, a person will not want to suffer this assault every year. So much the better to learn these plants and avoid them.