Despite the warm afternoon sun, the smattering of color on the trees at the State Hospital grounds in Traverse City is a subtle reminder: cold days are ahead. But now is the perfect time for exploring. The cultivated arboretum on the grounds can be a soothing respite for visitors today, just as it was for patients one-hundred years ago.

In 1882, while planning the construction of the Northern Asylum for the Insane (there would be three name changes before the final moniker, Traverse City State Hospital), the Board of Trustees put their faith in the plans set by Dr. Thomas S. Kirkbride, a prominent authority on mental health care in the United States during the last half of the nineteenth century. By establishing the asylum as a “Kirkbride Building,” the Trustees were making a statement about the type of care that would be available to patients therein. To sum up Kirkbride’s treatise on the construction of asylums, he believed that one’s surroundings could aid in mental health recovery; or, as local medical giant Dr. James Decker Munson would later put it, “beauty is therapy.”

Twenty-five years into its operation, Munson would describe the site the State Hospital now occupies as the perfect candidate for a Kirkbride building, in that “this tract possesses an almost ideal combination of those features pertaining to an ideal site: a dry, porous soil, consequently healthy, eastern front-age for the buildings, an elevation sightly yet sheltered, an ample supply of pure, artesian water, and excellent facilities for drainage.” Although the site naturally had many of the qualities that promoted its use as an asylum, the wild forested areas and ragged hills that dominated the immediate landscape were not calming tonics for the nervous mind.

Kirkbride advocated that the grounds of an asylum were an extension of the asylum itself, and should “be highly improved and tastefully ornamented; a variety of objects of interest should be collected around it, and trees and shrubs, flowering plants, summer-houses, and other pleasing objects, should add to its attractiveness. No one can tell how important all these may prove in the treatment of patients, nor what good effects may result from first impressions thus made upon an invalid on reaching a hospital”.

Many Kirkbride buildings have been demolished over the years, for as we are all aware, the care and maintenance of such structures is a costly endeavor. Fortunately, the State Hospital still stands, and the grounds are littered with many of the same varieties of trees that Munson and the Board of Trustees had planted as early as 1886.

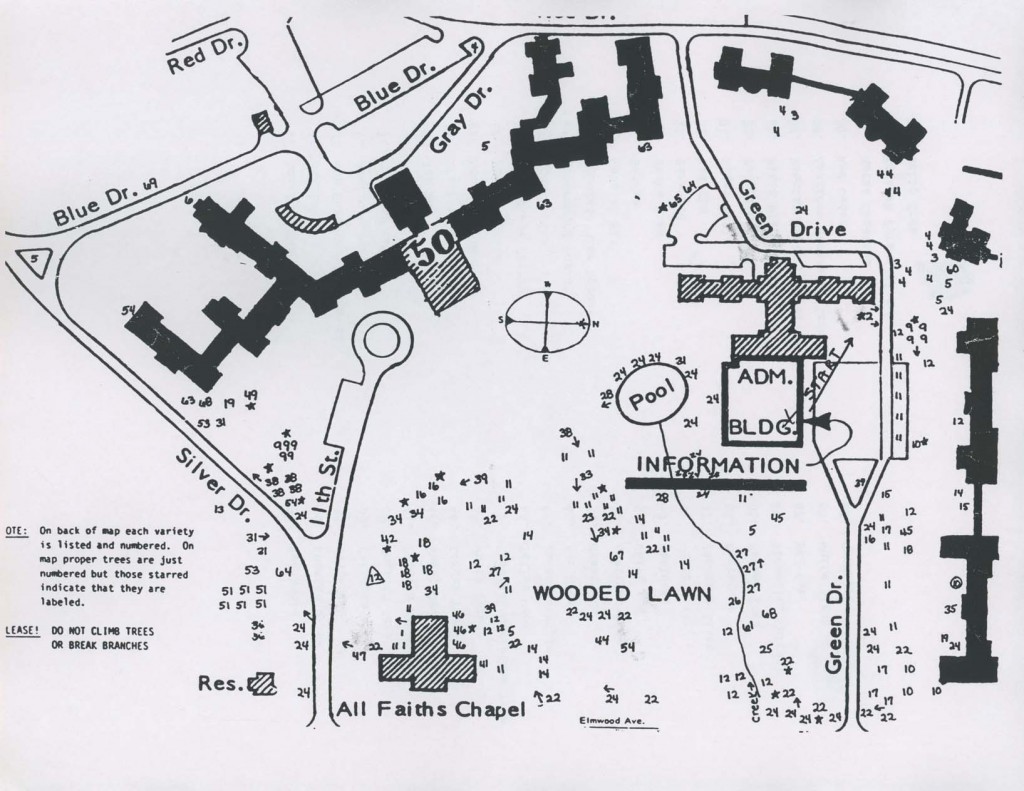

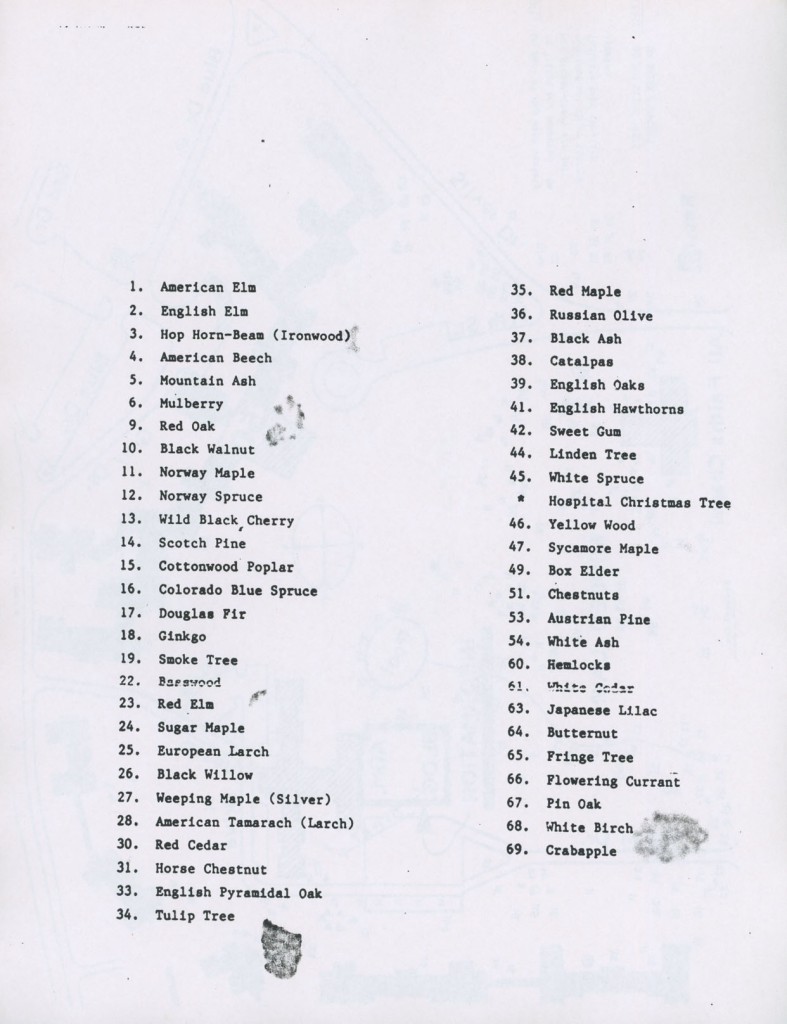

Care to walk the grounds with me? Print (or save to your mobile device) a copy of the map that appears at the end of this article, and we’re off!

The grounds immediately in front of the institution are really fine, and have many interesting and attractive features. They have been carefully planted with trees and shrubs, and with charming effect. Much attention was primarily given to the selection of the trees, and an effort was made to plant all trees that would grow in this latitude. Among them may be found the salis burea, Kentucky coffee, mulberry, box alder, pecan, walnut, butternut, chestnut, hickory, the native beeches, elms and maples, the purple leaf beech, elm, maple, and the Norway maples in many varieties. These trees have attained some size and lend much beauty and interest to the grounds.

James Decker Munson, Board of Trustees Report, 1910

This map is an interesting exercise; some of the roads and features are no longer present, as well as some of the trees, but it is still a decent reference for those wishing to traverse the arboretum. A librarian with a long memory at the Traverse Area District Library states that the map was created by the Michigan State Extension, probably in the mid-1980s, so it is clearly time for an update. That won’t deter us, though!

The map legend claims that starred trees are labeled; after attempting to remain faithful to the map, I would have to say there were at least two separate attempts to label the trees. Some of the stars are accurate, but ultimately I found more labels than the map indicates. Being no arborist, I brought along a handy-dandy tree identification field guide with me, which I checked out from Traverse Area District Library, Woodmere Branch. I am not exaggerating when I say this is essential for your visit. Also, give yourself two hours; I was able to cover the highlights in one hour, but missed some of the more remote sections.

With map and field guide in hand, I began on the south end of Building 50, looking for 49: Box Elder. Instead, I found a bizarre Austrian Pine, whose branches wrapped around and away from the building. Perhaps this native of southern Europe was reaching for more sunlight?

Near the Chapel, I located the Basswood referenced on the map (22), which lead to a happy discovery. Although all that remained of the original tree was a rotting stump, volunteer basswood trees were thriving all around the stump, making a neat refuge for little adventurers. That is the beauty of investing in nature; She has a tendency to give back more than we put in.

By Munson and Kirkbride’s reckoning, my visit was a success. I especially found the natural light-filtering qualities of the leaves of Catalpa speciosa to be particularly soothing to my frazzled, post-summer mind. You’ll find this native of southern Illinois close to the intersection at Silver Drive and 11th Street.

Ready to take the trek on your own? Remember, this arboretum is over 125 years old, so surprises abound. Enjoy the fall color, and don’t forget your map!

References:

Board of Trustees. “Report of the Board of Trustees of the Northern Michigan Asylum at Traverse City June 30, 1910,” available online through Traverse Area District Library’s local history collection: http://localhistory.tadl.org/items/show/2009.

Kirkbride, Thomas S. “On the Construction, Organization, and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane,” Chapter 22; available online through the National Institute of Health, US National Library of Medicine Digital Collections: http://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-66510280R-bk.

Mohlenbrock, Robert H. “MacMillan Field Guides: Trees of North America” (available for checkout at Traverse Area District Library).

Amy Barritt is co-editor of the Grand Traverse Journal.