by Carolyn J. Thayer

Editor’s Note: The author submitted this story as part of “Lifestory Center,” a memoir project spearheaded by Northwestern Michigan College’s Extended Education Services, funded by a grant from the Michigan Council for the Humanities, and archived by Traverse Area District Library. Grand Traverse Journal will be occasionally reprinting submissions to this collection, in an effort to call attention to this valuable resource. If our readers know any of the authors, we would love to contact them, so please let us know!

The following is a fun story about the Carmien Family and their unique nuclear living situation, submitted by Carolyn Thayer. Carolyn was the daughter of Willard and Irene Carmien:

The cars pulled to the side of the road in front of the group of houses, and the crowd was assembling. Someone asked, “What are they doing? Is it some kind of massive Spring-cleaning?” Someone else said, “It looks like they’re moving. But, all of them?” as they surveyed the furniture huddled in the yards of the three houses.

A few months earlier at a typical Carmien get-together, my mother, and dad, and several of Dad’s brothers and sisters were sitting around sipping beer and swapping jokes and stories. Some time during the reminiscing someone brought up the problem of housing.

The year was now 1949 and, as the party progressed, I heard my Uncle Keith say, “It is really getting tight for us in our little house since Barbara has been born. We really need more room.” And then my dad said, “We could use more room, too. I don’t know where we are going to put Nancy when she can’t be in our room anymore.” Sine we had moved into The Brown House my brother Jim, two years younger than me, and my sister, Nancy, ten years younger than me, had been born. Our house had one regular size bedroom, where our parents slept, with a crib for my baby sister, Nancy, and a tiny room, much like a walk-in closet, where my brother and I slept. This room was just large enough for a small closet and a six-year crib. My brother slept in the six-year crib, though he was eight years old, and I, at the age of ten slept on a bunk my dad had built on top of the crib. I usually slept curled up as my feet stuck out the end of the bed if I straightened out.

My Aunt and Uncle, living in the small house, were likewise, feeling cramped. Grandma was now living alone in the Big House which had one bedroom downstairs and two bedrooms upstairs.

I was ten years old at the time and I never knew who came up with the idea. They merely said, “Why don’t we swap houses?” Now you would have to know our family to appreciate how this idea was received. The suggestion was hailed with much laughter, after which everyone interjected a few of their own ideas into the discussion. “We’ll all leave our curtains,” from the women, and “I know where I can get a handtruck” from the men. Each suggestion was greeted with more laughter. As if anyone would ever do such a preposterous act!

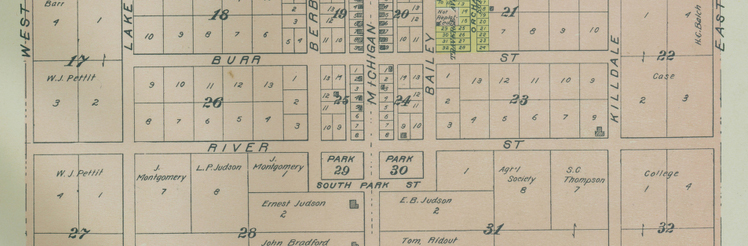

In the days that followed, however, the idea began to sound more sensible. My Dad owned all three houses so there was no problem there. Grandma was willing to move into the small house, as she didn’t need all the room she had in the big house. There was much fun made over the possibilities. As the subject was explored, the excitement grew. It was finally decided; in the Spring we would move. All of us. All at once. The same day.

As I remember, it was a weekend in April or May of 1949. By now there had been more get-togethers (a favorite pastime of our close-knit family) and strategy had been mapped out as to how to accomplish this undertaking. The troops were marshalled and all available hands were ready and eager to begin. The houses were close enough together, forming a circle with a common driveway, that taking furniture by truck was not feasible. what was so neat, though, was that everyone was moving clockwise into the next house. The smaller two houses were on a small knoll, so the fewer steps carrying heavy furniture the better. So they started at the Big House, carrying one piece of furniture up the hill to the small house where it was set on the lawn. Next, they carried a piece of furniture from there to the lawn of the Brown House, then a piece from the Brown House to the Big House. Thus it went all one day and into the next. We kids scurried from place to place carrying small items and boxes of precious possessions. I remember carrying my own treasures, (my toys and clothing), and table lamps, bedding, and kitchen items. It was fun for me, too, to help grandma move all of her small items into her new home. In the process some furniture and possessions were exchanged making it unnecessary to move everything.

It was a beautiful weekend, and the word spread quickly in our small town. Soon cars began to stop along our road and the main highway and a crowd began to gather to watch the residents of “Carmienville” and their latest scheme. Finally, the last piece of furniture was moved and the items sitting out on the lawn were in each house. All that was left was the settling in.

For me, it was a wonderful move! As much as I loved the Brown House, I was so ready to exchange my top bunk on the six-year crib, where my feet stuck out the end, for that big twin bed my Uncle Bruce gave me, and the little closet-sized room, I had had for the past nine years, for the huge bedroom I was to share with my two sisters (another sister was born four years later). My brother had the small bedroom on the landing upstairs, and my folks had a bedroom on the main floor which was more private for them. I remember climbing into bed the first night after the move and stretching out on that “Hollywood” mattress on that “big” twin-size bed with it’s own headboard and looking around at my huge bedroom with the sloping ceiling and thinking how fortunate I was.

Grandma settled in quickly into her cozy little home, and my Aunt and Uncle could spread their wings for awhile. They later built another house in the circle of “Carmienville” and welcomed three more daughters into their family. Sometime later, my dad’s sister, Mabel, and her husband, Dale, moved into the next house down the road and “Carmienville” expanded to five houses.

Through the years, when the family congregated, sooner or later someone would say, “Remember the time we all moved at once?” and it was named “The Fruitbasket Turnover.”

As a child of ten, I was blessed to be a part of a family who were so close and loved to be together, who were always conscious of each other’s needs and always there for each other through thick and thin. We laughed together, cried together, worked together, and played together. I felt secure in my family and extended family.

Now, fifty years later, I marvel at the speed and alacrity with which each family was willing to move for the general good. Though no one left the immediate vicinity, my mother left her gardens, she had so lovingly attended, to her sister-in-law and brother-in-law for them to enjoy. As time went on, the Hollyhocks and Mock Orange bloomed anew around our new home.

Though I had ten years of memories invested in the Brown House, I also came to have many years of memories of the Big House and , years later, as a young bride I was to live again, for a year, in the Brown House.

Through the years, I’ve never forgotten the Spring of 1949 and the “Fruitbasket Turnover!”