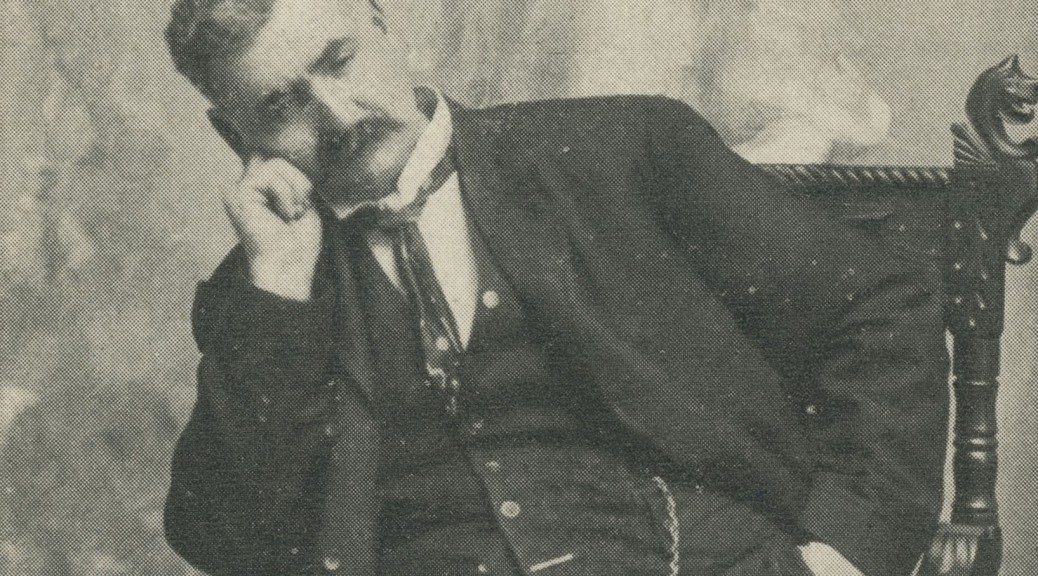

Scott Woodward (1853-1919) was a local author and publisher living in Traverse City at the turn of the last century. His work is firmly in the realm of realism, but it is often difficult to discern if his writings are autobiographical in nature, or if he’s just good at spinning a highly believable yarn. Woodward’s style is deftly described by George W. Kent, editor of Traverse City Daily Eagle circa 1910: “In his early life this author differed from his fellows in that his imagination was most vivid and he turned his visions, as some called them, into realities and wove them into his paintings of life in various phrases about him, taken from his peculiar viewpoint.”

The following is one entry in Woodward’s Life Pictures in Poetry and Prose, originally published in 1911, and tells the story of the felling of the last tree in a once-wide stand of pines. So romantic is the notion, that readers may be skeptical of his actual presence at the moment described, but the detail and memory cited gives one reason to believe his tale rings true.

“CUTTING THE LAST PINE.

The last pine- the lonely monarch in the midst of 2,000,000 feet of hardwood timber- is down. Its fall was one of the most pathetic sights I have ever had occasion to witness.

Through the courtesy of Frank Lahym, the lumberman, I found myself on a cold, frosty morning headed for camp. It was my good fortune to receive an invitation to be present at the cutting of the last pine to be found anywhere in the woods for miles around.

Great is the power of imagination, and before I was aware of it I was again among the scenes of thirty years ago.

THE SCENE CHANGES.

I was once more riding beneath the evergreens that hung low from the great load of snow they were supporting. In the distance I could here [sic] the steady “clip, clip” of the woodsman’s ax and the sharp ring of the saw, while away in the distance came the familiar warning, “Timber! Timber!” to all who might be in danger from the falling trees.

Again the scene changed with me and I stood beside the skidway and saw the great pines being loaded on sleighs with their 12-foot bunks. Log on top of log was being piled up on the sleighs until it looked like a veritable rollway for each team to take out.

The last log is rolled up into position, the familiar “chain over” is given and answered. The load is securely bound and then we start down the iced road to the river- I awake from my dream.

There is a jerk and a jolt and we find ourselves up-standing. One sleigh is fouled on the roots of a young sapling that some road monkey has unwittingly cut four inches too high.

Thus vanishes the dream of ’78 and with it the great rollway, the logging sleighs with their 12-foot bunks, the graded road which was kept in shape by the sprinkler over night, the overhanging trees that always had a weird and ghostlike appearance when clothed in their mantle of snow, and, last of all, the great banking ground where still flows the waters of the Manistee.

THE DINNER HORN CALLS.

We consign them all to the memories of thirty years ago, when I, too, was a unit in that great industry that will never return. We reach camp just as the great dinner horn is calling from labor to refreshments, and the lumber jacks come steaming in from their cutting of hardwood.

But it has changed, all changed. We sit down to a table loaded with roast beef, bread and butter, potatoes and coffee, capped out with pie and cookies. Ye gods, but what must one of our boys of ’78 have thought had he sat down to such a meal. However, we bolt it down while I think of the days when men sat around a fire in the woods and ate their beans and hard bread with good old “New Orleans” for dressing, and were satisfied. Had a man kicked on that he would have been hooted out of camp and compelled to take the hay road between two days.

In the midst of two million feet of hardwood in town 26 north of range 11 west stood one of the most beautiful cork pines that ever grew, three feet six on the sump, and where cut made five fourteen, one twelve and one sixteen-feet logs. When scaled by Doyle’s it measured a bit better than 3,000 feet. We had cut larger trees in ’78, as well as smaller ones, but none better. I counted the rings on the stump and came to the conclusion that this one pine had stood alone as a landmark, or sentinel, defying the storm and wind for better than 200 years, and had even escaped in days past the vandalism of the timber thieves.

I loved the pine, not for its intrinsic value alone, but for the memory it awakened. However, the time had come to cut and fell this last monarch. The hardwood was being cut around it. Huge piles of tops and brush were in every direction. It might survive until some future day in the hot summer, when some unthinking halfwit would drop a match in the dry tinder of the slashing. The prospect would be similar to that already seen in sections of Wexford, Roscommon, Kalkaska, Grand Traverse and many other counties.

After getting several good pictures of the landscape and the tree from various positions, I watched it being cut and skidded ready for the hauling.

Then, as the day was advancing, I was called to the sleigh for our return trip to the city. Strange it may seem. No one but an old lumberman can understand when I say I was both glad as well as sorry, to be present at the cutting of the last pine.”

Woodward, Scott. “Cutting of the Last Pine.” Life in Pictures in Prose and Verse. Traverse City: Scott Woodward, 1911. 133-136.

Amy Barritt is co-editor of Grand Traverse Journal. Beautiful pieces of prose and poetry reside unexplored in the rare books collection in the Nelson Room of Traverse Area District Library, and she invites you to come and find yourself a long-lost treasure.

HAVE A COPY OF THE BOOK “LIFE PICTURES” WITH THE EXACT PICTURE IN IT. THE INTRODUCTION WAS WRITTEN BY GEO. W. KENT EDITOR TRAVERSE CITY DAILEY EAGLE

You’re pretty lucky, Charles! This is a great book. It really shows Woodward’s humor and whimsy. I don’t know how many copies still exist, but I imagine it was originally a pretty limited, local run.