MURDEROUS ASSAULT.

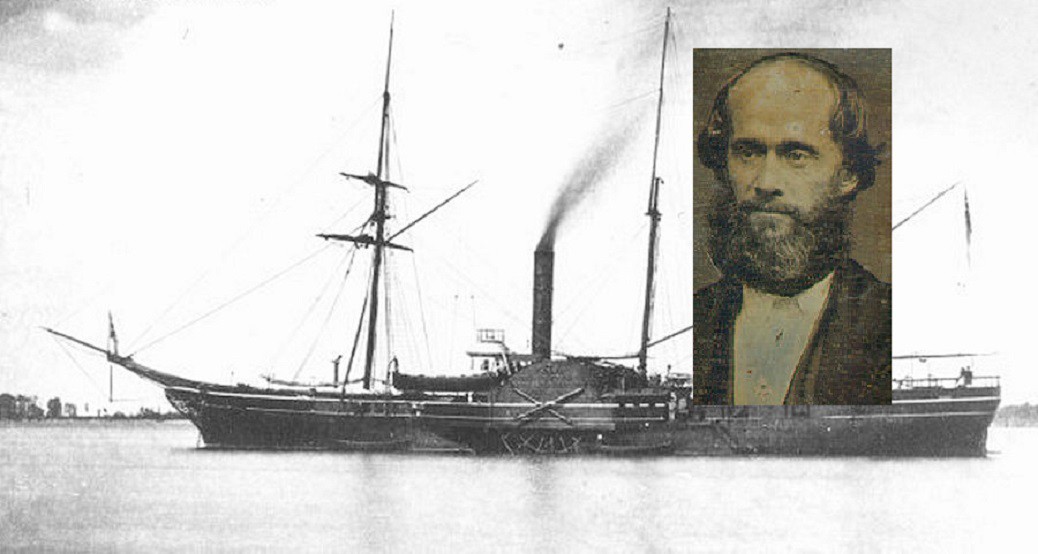

On Monday last the U.S. steamer Michigan entered this harbour at about 1 o’clock, P.M., and was visited by the inhabitants promiscuously during the afternoon.

At about 7 o’clock Capt. McBlair sent a messenger (Alexander St. Barnard, the Pilot) to Mr. Strang, requesting him to visit him on board. Mr. Strang immediately accompanied the messenger, and just as they were stepping on the bridge leading to the pier in front of F. Johnson & Co.’s store, two assassins approached in the rear, unobserved by either of them, and fired upon Mr. Strang with pistols. The first shot took effect upon the left side of the head, entering a little back of the top of the ear, and rebounding, passed out near the top of the head.

This shot, fired from a horse pistol, brought him down, and he fell on the left side, so that he saw the assassins as they fired the second and third shots from a revolver, both taking effect upon his person, one just below the temple, on the right side of the face, and lodged in the cheek bone; the other on the left side of the spine, near the tenth rib, followed the rib about two inches and a half and lodged.

Mr. Strang recognized in the persons of the assassins Thomas Bedford and Alexander Wentworth. Wentworth had a revolver, and Bedford a horse pistol, with which he struck him over the head and face, while lying on the ground. The assassins immediately fled on board the U.S. steamer, with pistols in hand, claiming her protection.—Northern Islander, June 20, 1856 (1)

The story of James Jesse Strang’s murder is told here in the style of nineteenth century journalism to describe the brutality of the scene. Captain McBlair of the naval vessel Michigan transported Bedford and Wentworth to Mackinac Island, where, after a few minutes in jail, they were released to the celebration of the crowd gathered there. They were never tried for the murder.

Questions surround this bloody narrative, questions that arise from such powerful feeling that four accounts of the Mormon presence on Beaver Island have been written in the last century and a half, each with a unique perspective. The first question has to do with the motivations of the protagonists: What climate of hatred enabled murderers to receive a hero’s welcome at Mackinac Island?

The answer to that question is simple according to an early telling of the story serialized the Grand Traverse Herald in 1883. (2) D. C. Leach states unequivocally that the Mormons were murders and thieves. He describes plundered shipwrecks, stolen horses, fishing nets destroyed or hauled away, and vile acts of piracy committed all along the shores of Lake Michigan. His view represented that of most residents of Northern Michigan at the time, though his reporting is colored by the sources he chose to include. Since Mormons had all but been driven out by 1883, he had little opportunity (nor interest) in hearing the other side.

Milo Quaife published another account of the settlement of Beaver Island in 1930, The Kingdom of St. James. Examining documents friendly to the Mormons, including the first newspaper of Northern Michigan, The Northern Islander, he concluded that tales of murder and pillage had been much overblown. (3) Nation-wide, powerful prejudice against Mormons prevailed, not just locally against the Strangite, Beaver Island settlement, but against the Brighamite (Utah) Mormons generally. Before and after the assassination of Joseph Smith in 1844, only twelve years before the assassination of Strang, Mormons were accused of murder and “consecration” of non-Mormon property. The press was unfavorable to Mormons, frequently publishing hearsay accounts of Mormon atrocities and ignoring the provocative acts committed against them.

For more than five years The Northern Islander attempted to rebut outrageous tales of Mormons putting out lighthouse lights to cause shipwrecks, outright murder and later desecration of the body during an autopsy, and even the attempted kidnapping of a child on Old Mission Peninsula with a view towards making him the new ‘King of the Mormons.” However much the newspaper tried to present its side in the conflict, it could never overcome the array of newspapers lined up against it: The Buffalo Rough Notes, Cleveland Plain Dealer, Detroit Advertiser, Green Bay Spectator, and numerous others. (4) Depending upon hearsay for news stories, they would continue to defame the Mormon kingdom, inflaming the citizens of the area with accounts of ruthless Mormon evil-doers.

The latest two books about Beaver Island Mormons, Assassination of a Michigan King, by Roger Van Noord, (5) and “God Has Made Us A Kingdom,” by Vickie Cleverley Speek (6) add further details to the conflict between Mormons and non-Mormons in the Straits area. Both assert that the doctrine of “consecration,” the teaching that property of individuals could be seized by the Church” was certainly practiced by Mormons upon Beaver Island as apostates left their farms and businesses and probably practiced by Mormons upon non-Mormons (partly for pay-back for deeds done against them), but to a far lesser degree than contemporary newspaper accounts described. There is no convincing evidence that James Strang was ever directly involved in planning raids against non-Mormons. In fact, perhaps due to his training in the legal profession, he consistently attempted to follow to the letter the laws of the United States and Michigan as evidenced by the facts that he gave himself up when charged with federal crimes in 1851 and readily agreed to meet with Captain McBlair that fateful day in 1856 even though he had s misgivings about the presence of the U.S. S. Michigan at the Beaver dock that day. Strang’s views about the sanctity of the law are expressed in this excerpt printed in the Northern Islander in 1851:

Many have looked for the downfall of the nation by the array of the north against the south. That will not be. The nation will perish in the anarchy of laws despised and trampled on by the whole people. There is no wickedness, no act of oppression ever undertaken by a despotic government, which has not been successfully accomplished in this. There is no conceivable act which cannot be done under it, either in accordance with the law or in spite of it. The most influential men in society, are many of them engaged in the constant and shameless violation of penal statutes and criminal enactments, without so much as being less respected. The end of all this can be nothing less than the despising of magistrates, trampling on law, and the crumbling in pieces of the government. (7)

It is difficult to reconcile this statement asserting the importance of obedience to the law with the accusations of lawlessness directed towards Strang by the press.

Strang defended the conduct of Beaver Island Mormons strenuously. Denying that “consecration” had been practiced against non-Mormons, he pointed to the fact that not a single Mormon had been convicted of such crimes, even though Beaver Island was for a long time under the judicial control of Mackinac, the heart of opposition to the Mormon settlement. Furthermore, he insisted, crimes committed on the waters of Lake Michigan could be prosecuted in any county bordering the Lake. Why is it, he asked, that not a single case had been taken up against the Mormons? Of course, the question was rhetorical; there was no evidence of wrongdoing so no trial could be commenced.

Another question concerning Strang’s murder comes from the events directly following the act. What were the consequences of the assassination on the inhabitants of Beaver Island? An armada of boats from Mackinac and nearby islands and towns quickly assembled to drive the Mormons away from Beaver. Well-armed, the fishermen and traders came expecting a fight, but were surprised to find that the inhabitants meekly agreed to leave the Island and all their possessions behind, board passing boats heading for Milwaukie, Green Bay, and Chicago, and make their lives elsewhere.

By the last commands of their fallen king, James Jesse Strang, they were instructed to comply with the demands of the invaders for, despite his terrible, disfiguring wounds, he had initially survived the attack [he died 23 days later in Voree, Wisconsin]. Though paralysed, he was lucid, and directed his followers to “take care of their families.” This instruction, consistent with his lifelong abhorrence of violence, was clearly the wisest course of action; one Mormon later wrote that he believed there were fewer than fifty firearms on the Island altogether.

So it was that vessels came to St. James on July 3, 1856, filled with bands of armed men ready drive the Mormons out. What occurred there was a scene of plunder, arson, and chaos such as had never been seen in Northern Michigan. One description left behind tells of the misery inflicted upon the Mormon inhabitants:

Discovering the people were docile and leaderless, the invaders began their work of “robbery and general destruction” throughout the island. “They came marching through the streets of St. James ordering all Mormons to leave and giving them only 24 hours to do it or be shot,” Elvira Field noted. “Those individuals who tried to oppose the mob and defend themselves were thrust into the street and their houses burned. The Mormon tabernacle on the hill was torched, as were storehouses, businesses, valuable dwellings and the Mormon printshop.”

Pleased with the arson the pillagers had initiated, Thomas Bedford proudly announced that “it would have been cheaper to buy a new printing office than to attempt any work of publication at the one left by Strang.” The prophet’s house and property were especially targeted for plunder and ransacking. His household goods and extensive library were thrown into the street and trampled in the mud. To show their hatred of Strang, the attackers shot at everything on the premises. Strang’s large poultry yard with the rare Plymouth Rock chickens John C. Bennett had sent as a coronation gift was “made a shooting-mark for all.” The mob went looking for Strang’s wives. “My friends advised me to keep out of sight,” Sarah Wright (one of Strang’s wives) recollected. “I was told some rough had said he would like to find Strang’s young wife—but I was not found.” She explained that Mormons were helpless because they did not know if Strang was still alive and had been told not to resist. (8)

Three hundred-fifty Mormons were loaded aboard the steamer Buckeye State, herded like cattle and unable to take their possessions on board. They were taken to communities in Green Bay, Milwaukee, Racine, and Chicago, where they were left to fend for themselves. In Chicago, one kind soul berated the mob assembled to oppose the new arrivals and opened the doors to a warehouse. “ Here, ladies and gentlemen, come in here out of the sun and stay until you can find places” he said, expressing the first kind words the Mormons had heard since leaving the Island.

After leaving Beaver, the Strangite Mormons suffered greatly; most had lost all their possessions; many had to depend upon the kindness of relatives for survival; some had to conceal their religion from the community in order to avoid banishment. They were outcasts in their own land with some, by necessity, forced to pick blueberries and cranberries for their survival. Without a leader, they drifted back to scattered settlements throughout the Midwest, blending in with surrounding populations. Though a few hundred Strangites survive today, the movement has largely disappeared from the scene, much as the Shakers had disappeared earlier.

Finally, the question concerning the role of the United States Navy must be answered: Did Captain McBlair of the U.S.S. Michigan collude with the murderers and actively participate in the plot? Circumstantial evidence is there in abundance:

That Commander McBlair or other officers of the Michigan were in on the assassination conspiracy is still in question. The following factors, however, would not have been overlooked had the case gone to court. Commander McBlair was at best thoroughly unsympathetic with Strang’s cause; this gave him a motive. McBlair met with the chief conspirators just days before the assassination and was officially very sympathetic to their public cause of escaping the island [after the assassination]; this allowed him to participate in the plot. In addition, if the commander was as eager to protect the dissidents as he professed in his June 6 report to the governor of Michigan, why did he dally for ten days, even visiting Milwaukee before going to Saint James? This delay clearly gave the assassins time to arrive at Beaver and even to practice with the murder weapons before the vessel’s arrival. (9)

Furthermore, the failure of the Michigan to protect the Mormon residents of Beaver after the assassination of Strang points to Captain McBlair’s sympathy with partisans who desired to expel the Mormons. At the time the mob was pillaging the Island, the warship was cruising Lake Superior, unable to respond to possible orders requiring him to defend the Mormons who were being dispossessed of their property. With the authority of the United States Navy, McBlair and his crew could have stopped the ravaging of Beaver. Someone—McBlair, most likely, or even a superior—made a decision to sail away from the chaos that exploded on July 3, 1856. We will probably never know with certainty the whole story, though we can ask one more important question: Was the United States government involved in any way with the plot to kill James Jesse Strang?

There is no smoking gun that points to such involvement, though certain lines of evidence indicate possible foreknowledge and, perhaps, approval of the actions of McBlair in leading to the assassination. We know that in 1853 the fishermen of Mackinac did formally petition the Governor of the State of Michigan and the President of the United States to respond to the alleged depredations of the Mormons in the Mackinac region. (10) We know that newspapers maintained a hostile climate towards the Strangite Mormons from the colony’s inception. We know that in 1856 Brighamite Mormons in Utah were charged by the Attorney General of the United States with six abuses carried on by Brigham Young’s governance, among them the accusation that lives and property are at risk from any who oppose the authority of the Church. (11) The federal government might wield the same brush of condemnation against Beaver Island as it did against the Brighamites in Salt Lake City, thereby provoking the Federal government to sanction Strang’s murder. Finally, the inquiry made in Washington was a most perfunctory affair with the important questions never asked. (12) A people dispossessed of their land and property were quickly disposed of and forgotten by the United States government and by the nation generally. The expulsion of the Beaver Island Mormons on July 3, 1856 does not remind us of the ideals this nation was founded upon nearly 80 years earlier.

Whatever opinion the reader holds concerning the unjust treatment meted out to the Mormons of Beaver Island, one fact stands out as incontrovertible: In the 1850’s Northern Michigan was a lawless place. There was theft and plunder; there was occasional murder; there were courts that acted unlawfully whether through ignorance of court officials or through malice; there were Indians, not yet socialized to the ways of white culture, who were fair prey for vicious traders; and there was persecution enacted by both federal and state elected officials who exceeded their authority in the actions they perpetrated. The Sheriff of Mackinac County would arrest Strang over and over, each time the case being thrown out because he was unable to show cause for the arrests. Posses of thugs and hooligans were assembled to hunt down “felons” who had committed no crime but the enforcing of temperance laws. Captain McBlair, without the judicial authority, collected depositions from the co-conspirators that murdered Strang while ignoring evidence of his innocence. Later, in the 1870’s the governor of Michigan, Kinsley S. Bingham flatly denied the State had any role in indemnifying Mormons who had lost their possessions in the ravages of 1856. (13) Lawlessness was the rule at every level: local, state, and federal. In telling this tragic story, we must resolve never to allow it to happen again.

NOTES

1 The Northern Islander was the first newspaper of Northern Lower Michigan. It began publishing in 1850 and ended publication with this note concerning the assassination.

2 Leach, M.L. A History of the Grand Traverse Region, Traverse City, MI: Grand Traverse Herald, 1883.

3 Quaife, Milo M., The Kingdom of St. James: A Narrative of the Mormons, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1930

4 The power attributed to the press by the American people is described in Dicken-Garvin, Hazel, Journalistic Standards in Nineteenth Century America, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press,1989, 48.

5 Van Noord, Roger, Assassination of a Michigan King, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1988

6 Speek, Vickie Cleverley, “God Has Made Us A Kingdom”: James Strang and the Midwest Mormons, Salt Lake City, Signature Books, 2006

7 Northern Islander, April 3, 1851.

8 This description is taken from Speek, p. 228.

9 This passage as well as the point made in the following paragraph comes from Rodgers, Bradley A., Guardian of the Great Lakes: The U.S. Paddle Frigate Michigan, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996,

10 The petition is presented in the Detroit Daily Free Press, May 24, 1853.

11 The six charges against the Utah Mormons are given in Albanes, Richard, One Nation Under Gods: A History of the Mormon Church, New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 2002.

12 The inquiry is described in Van Noord, 267-8.

13 Van Noord, 268.

Richard Fidler is co-editor of Grand Traverse Journal.

The pilot of the USS Michigan sent ashore to see Strang and request he visit Captain McBlair was Alexander St. Bernard of St. Clair, Michigan, not San Barnard!!

Thank you for the correction. The manuscript has been changed to reflect your input.