By Richard Fidler, Co-Editor of Grand Traverse Journal

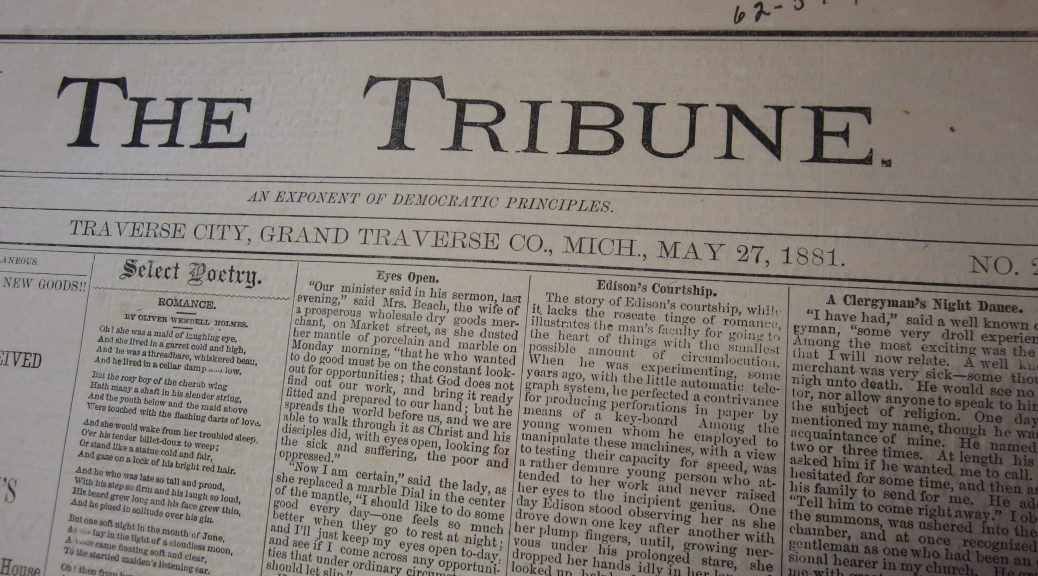

An archives can reveal hidden treasures to investigators with the patience to wade through boxes of records often as uninspiring as ledgers of collapsed businesses and minutes of fraternal organizations. Marlas Hanson uncovered one of them recently: a stack of newspapers never before recognized by historians as a resource for local news. There were about twenty copies of them, all dated in the year 1881. What could they tell us about the area that our other paper of the time, the Grand Traverse Herald, did not? This is a question that sets a historian’s heart racing—a new source of information.

Alas, upon examining issue after issue, it became apparent to us that the Tribune had precious little in the way of stories about the Grand Traverse region. It was a political paper favoring the Democrats, perhaps a counterbalance to the Herald, a thoroughly Republican outlet. Most newspapers of the time were explicitly Republican or Democrat: neutrality was not common. The later merging of the Evening Record, a paper with links to Republicans, with the Morning Eagle, a Democratic organ, formed the Traverse City Record-Eagle, a newspaper less partisan than most others.

Unlike the Herald, the Tribune dwelled mostly upon party conventions held elsewhere and descriptions of the nasty things Republicans were doing to the country at the time. It carried no long, detailed accounts of fires, weather events, and happenings about town, and little in the way of editorial reflections on local issues of the day. In short, it was a disappointment.

Still, one can find gold among the dross. Editors at the time had a gift for story-telling, a gift seldom displayed by present-day editors who use the dry, formal language of today’s news rooms. They frequently wrote about their feelings and things that happened to them, spinning complex sentences that astound us today with their style and expressiveness. By contrast, when editors raise their voices these days, it is only about their views on issues, local, state, or national. They do not let us know about their lives, unlike newspapermen of the 1880’s. One personal story captured from the Tribune’s editorials moves us to tears even now, more than a hundred and twenty years later. Though unsigned, it was probably written by Albert H. Johnson, editor and founder of the Tribune.

For background, Johnson previously had started the Leelanau Enterprise, but moved on to tackle the Traverse City market after that venture. We do not know how long the Tribune, lasted in the city—perhaps not long, given the preponderance of Republicans in the area at this time. Since the area has voted quite consistently for Republicans, a Democratic newspaper would not do well in such an environment. However long it lasted, the paper did leave us this story about Johnson’s grief at the death of his young son. It speaks to us across time about the universality of human suffering.

“In the Bottom Drawer

H. Johnson, editor

I saw my wife pull out the bottom drawer of the old family bureau this evening, and went softly out, and wandered up and down, until I knew that she had shut it up and gone to her sewing. We have some things laid away in that drawer which the gold of kings could not buy, and yet they are relics which grieve us until both our hearts are sore. I haven’t dared look at them for a year, but I remember every article.

There are two worn shoes, a little chip hat, with part of it gone, some stockings, pants, a coat, two or three spools, bits of broken crockery, a whip, and several toys. Wife, poor thing, goes to this drawer every day of her life and prays over it, and lets her tears fall upon the precious articles, but I dare not go.

Sometimes we speak of little Jack, but not often. It has been a long time, but somehow we can’t get over grieving . He was such a burst of sunshine into our lives that his going away has been like covering our every day existence with a pall. Sometimes, when we sit alone of an evening, I writing and she sewing, a child on the street will call out as our boy used to, and we will both start up with beating hearts and a wild hope, only to find this darkness more of a burden than ever.

It is so still and quiet now. I look up at the window, where his blue eyes used to sparkle at my coming, but he is not there. I listen for his prattling feet, his merry shout and his ringing laugh, but there is no sound. There is no one to climb over my knees, no one to search my pockets and tease for presents, and I never find the chairs turned over, the broom down, or ropes tied to door knobs.

I want someone to tease me for my knife; to ride on my shoulder; to lose my ax; to follow me to the gate when I go, and be there to meet me when I come; to call “good night” from the little bed now empty. And wife she misses him still more; there are no little feet to wash, no prayers to say, no voice teasing for lumps of sugar or sobbing with the pain of a hurt; and she would give her own life almost, to wake at midnight and look across to the crib at midnight and see the our boy there as he used to be.

So, we preserve our relics, and when we are dead we hope that strangers will handle them tenderly, even if they shed no tears over them.”