by Julie Schopieray, local author and history enthusiast

In a small, isolated town as Traverse City was in the late 1800s, a sudden illness or serious injury was treated in one of the several doctors offices in the city. These offices were generally small, dark and ill-equipped compared to what we experience today, but this system of treating the ill was normal for small towns across the country. All medical care was primitive compared to what we are now used to. Many maladies were treated with elixirs and herbal remedies. Poor sanitary conditions resulting in infections was the most common reason for deaths. The lack of regulations monitoring medical education and licensing was still years away. Most local physicians were as qualified as they could be, but this was the typical medical care available in Traverse City and other small towns in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

The Traverse City asylum had a staff of physicians and nurses for the patients, but was not open to treat the public. As the city grew, the need for a general hospital was widely discussed and debated, but it wasn’t until 1902 when an opportunity to open one presented itself.

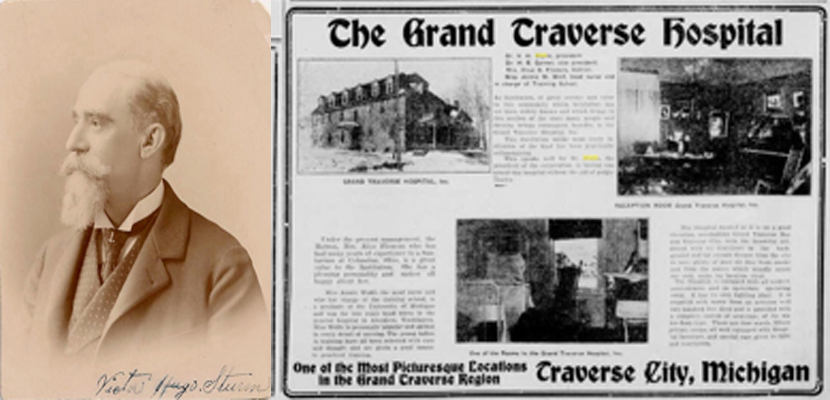

At the intersection of what is now M-72 and M-22 in Greilickville, was a summer resort called the Spring Beach Hotel. It was owned by a group of four Indianapolis physicians and had been a summer-only health resort which opened around 1896. After two of the original owners passed away, the remaining owners decided to sell it. The property included a hotel building and barn on thirty acres of land with a view of the bay. Dr. Victor Hugo Sturm and his partner Harvey P. Hurley of Chicago, purchased the resort with the plan to continue it as a summer health resort. They advertised it in homeopathic medical journals as the Grand Traverse Health Resort.

At the intersection of what is now M-72 and M-22 in Greilickville, was a summer resort called the Spring Beach Hotel. It was owned by a group of four Indianapolis physicians and had been a summer-only health resort which opened around 1896. After two of the original owners passed away, the remaining owners decided to sell it. The property included a hotel building and barn on thirty acres of land with a view of the bay. Dr. Victor Hugo Sturm and his partner Harvey P. Hurley of Chicago, purchased the resort with the plan to continue it as a summer health resort. They advertised it in homeopathic medical journals as the Grand Traverse Health Resort.

At first, their aim was to continue it as a retreat-type summer health sanitarium as it had been, but when they realized that the community needed a real hospital, they decided to permanently open it to all of the physicians in the area. The hotel building first needed some updating to make it into a hospital, so Dr. Sturm and his investors added on to the main building, spending about six thousand dollars in improvements for the new business.

Dr. Sturm arrived to make Traverse City his permanent home the first of January 1903, bringing his new bride, Sylvia. They took an apartment in the sanitarium building as their residence. Sylvia would take an active role in running the hospital as manager, serving on the board as secretary and treasurer and in later years, working to coordinate the nursing staff. A well-educated woman, she had attended Oberlin College and University of Michigan. With her husband out of town regularly on business, he left the hospital under her capable management. His involvement was minimal except for the initial investment.

Dr. Hurley provided funds for the city to buy an ambulance, which would be available to transport patients from their homes or doctors’ offices to the hospital. An agreement was made that the ambulance would not be used for anything outside the city, and they arranged for the chief of police to have charge of the vehicle. Mr. Murray of the Gettleman Brewing Co. offered his team of horses which he kept at his business and stated that his team will be at the disposal of the city for use on the ambulance at all times, night or day. The new hospital, at first, did not have an in-house physician, but there was always a nurse on staff, and it was open at all times for any doctor in the city to use.

The support staff included a cook, laundresses and house keepers. The large grounds had gardens where staff raised vegetables used in the meals for patients. By the end of 1907, seven full time nurses were employed including night staff, and two nurses remained available for private calls throughout the city when needed. A nursing program was established and training began in 1907. The call went out to recruit young ladies of the city to enter the program.

The support staff included a cook, laundresses and house keepers. The large grounds had gardens where staff raised vegetables used in the meals for patients. By the end of 1907, seven full time nurses were employed including night staff, and two nurses remained available for private calls throughout the city when needed. A nursing program was established and training began in 1907. The call went out to recruit young ladies of the city to enter the program.

The hospital served the city well for four years, but by 1907 it became clear that the facility was too small. A major renovation and expansion was planned with a 20-room annex addition. Local architect Jens C. Petersen was hired to design the new, up to date facility. The Evening Record described the hospital in glowing terms: The annex will be entirely modern and sanitary in every particular…There will be separate wards for the male and female patients… There will be a large surgery with a recovery room attached…for performing difficult and delicate operations. Arrangements have already been completed for the establishment of a training school for nurses in connection with the hospital and the staff will be composed of leading physicians of northern Michigan. An elevator was installed in the three story addition and a separate cottage was used to house contagious patients. The outdated kerosene lamps throughout the building were replaced with much brighter acetylene gas lamps, especially improving the visibility for surgeons in the operating room.

The hospital served the city well for four years, but by 1907 it became clear that the facility was too small. A major renovation and expansion was planned with a 20-room annex addition. Local architect Jens C. Petersen was hired to design the new, up to date facility. The Evening Record described the hospital in glowing terms: The annex will be entirely modern and sanitary in every particular…There will be separate wards for the male and female patients… There will be a large surgery with a recovery room attached…for performing difficult and delicate operations. Arrangements have already been completed for the establishment of a training school for nurses in connection with the hospital and the staff will be composed of leading physicians of northern Michigan. An elevator was installed in the three story addition and a separate cottage was used to house contagious patients. The outdated kerosene lamps throughout the building were replaced with much brighter acetylene gas lamps, especially improving the visibility for surgeons in the operating room.

Dr. Vaughn, head of the Chicago Union Hospital, toured the new, improved facility while on vacation in the summer of 1907 and gave his approval. His praise was gladly received. The city had desperately needed the services of a general hospital and all was going well. The hospital investors filed articles of incorporation in the summer of 1909 and it became the Grand Traverse Hospital, Inc.

As the only hospital in town, the citizens of Traverse City and surrounding areas now had a modern hospital with full services. When a local doctor could not treat a patient in their home or in their office, they were sent to the hospital. Cases treated included everything from illnesses including appendicitis, hernias, pulmonary tuberculosis, cancer and typhoid fever. Others were treated for injuries from occupational hazards such as railroad workers being hit by or falling from trains, a woman who lost both feet after they were run over by an engine near her job at the starch factory, a farmer who fell from a hay mower, and a firefighter who was overcome by smoke. There were those admitted as a result of accidents, such as carriage collisions, a man who was aboard the steamer Leelanau was scalded when the boiler exploded, and injuries from misfiring rifles. Other injuries were self inflicted. One woman died after a self-inflicted suicidal gunshot wound became infected. Another ingested carbolic acid in a suicide attempt, but survived.

Hospital statistics for 1909 were printed in the paper: 144 cases admitted, 85 total operations- 45 of those were major, 10 deaths, and a daily average of 5 patients.

By the end of the year however, everything came crashing down. On December 28, 1909, while on a business trip for his pharmaceutical supply company, Dr. Sturm was found dead in his sleeping berth on a train, near Mason City, Iowa after suffering an apparent heart attack. His body was taken to Anderson, Indiana where a daughter from his first marriage lived.

Only a few weeks after the announcement of Dr. Sturm’s death, the remaining stock holders decided to close the hospital. On March 31, 1910, the doors were closed for good, leaving the city once again without a hospital. The abrupt end was not just because of the death of Dr. Strum, but also had to do with a large law suit brought against them by the husband of a patient who died after being treated at the hospital. James Murchie, an alderman of the city charged the hospital with serious mistakes made while his wife was in their care in 1909.

Mrs. Murchie had been suffering from kidney stones and was treated with a common method– using turpentine as an enema. She was sent home after a time, but after a few weeks, her husband took her to an Ann Arbor hospital when it was discovered that she had several kidney stones which needed immediate surgery. After the surgery, an infection set in and she died.

Her husband charged that an alleged mistake at the Traverse City hospital was directly responsible for her death, claiming that the nurse mistakenly administered carbolic acid rather than turpentine when his wife was given the enema treatment normally used for her type of symptoms. The bereaved husband sued the hospital for $10,000, claiming hospital workers contributed to her suffering.

The Evening Record reported the findings of the jury: “…no verdict could be rendered against the defendant under the theory of plaintiff’s claim for damages under the charge as given relative to the administration of carbolic acid as an enema, as no witness expert or otherwise, testified to this as a fact. Furthermore, the newspaper went on, …there is no evidence which tended to show that the nurse in question was at all… incompetent, or that the appliances and conveniences furnished at the hospital were in any way faulty, unclean or improper. Therefore, the jury concluded, …under the undisputed evidence in this case, if by any possibility any person is liable, it would be the nurse in charge and not the owners or interested parties in the hospital.”[Traverse City Evening Record, 3-16-1910] Mr. Murchie was ultimately granted $2,385 in damages.

After being closed for two years, the hospital was re-opened in 1913 under the management of Mr. and Mrs. A.L. Smith of Leland. Mrs. Smith was a trained nurse and was in charge of the nursing department. Members of the Grand Traverse Medical Society in both Grand Traverse and Leelanau counties used the facility. Its tenure was short-lived, however, when the building caught fire in March 1915 and burned to the ground. There were only four patients in the building at the time and everyone was able to get out.

Once again, lacking a general hospital for its citizens, the community felt a desperate need for a new facility. James Decker Munson of the N. Mich. Asylum responded by opening a general hospital for the community, at first in an old residence on the asylum grounds. In 1925 a large, modern hospital became a reality just north of the asylum. From that small beginning (which still exists under the complex), the Munson hospital facility has grown into what it is today.

A Sidelight about Dr. Sturm

Dr. Victor Hugo Sturm’s real story was not known when he came to Traverse City. He began to use the fictitious title of “doctor” when he became the vice president and lead sales agent for Luytie’s Homeopathic Pharmacy in St. Louis. There is no evidence that he had any medical training at all, or that he actually treated patients, other than selling them the herbal elixirs he was hired to promote.

A German-born son of an eccentric man who claimed to have been the personal physician of Napoleon, he earned his living a traveling agent for a liquor producer in the early part of his career. First married about 1856, he and his wife Mary had three daughters, only one of them surviving to adulthood. During the Civil War he ran a sutler’s store and was the postmaster in Cumberland Gap, Tennessee.

In 1874 his name made newspapers across the south when he hired a lawyer to file divorce papers in a different state from his actual residence against his wife Mary without her knowledge. In the mean time, he ran off with a woman whose husband had just suddenly died (possibly by suicide), married her, and filed to adopt her children.

When Sturm’s real wife found out, she refused to divorce him, and, in an act of revenge, proceeded to expose him by submitting letters in the newspaper claiming he threatened her life in order to influence her to grant him a divorce. The whole affair resulted in V.H. Sturm being arrested in June 1874 for bigamy, since divorce papers drawn up in Indiana were invalid in Tennessee.

The newspapers had a field day with the whole thing. One clever reporter in the Cincinnati Inquirer wrote, “ Mrs. Castien[sic] of Macon, Georgia… has just married Major Sturm. There is a Mrs. Sturm at Knoxville, Tennessee, who says that if he has procured a divorce it has been without her knowledge or consent. There is a Sturm brewing evidently.”

Ultimately, a divorce was granted and Sturm took his new wife Eppie Bowdre-Castlen and her three children to California, where he worked as a traveling agent for C. Conrad Co., a liquor distributor. They settled in San Francisco, but by 1885 this marriage, too, ended.

Eventually, he headed back east and and in the mid-1890s landed in St. Louis, becoming the vice-president for Luytie’s Homeopathic Pharmacy Co. It was at this time he began to refer to himself as “Dr.” Sturm. His long experience as a smooth-talking salesman allowed him a lasting career with the Luytie’s company as one of their top agents. He traveled the country peddling these herbal remedies, and by 1900 had established offices in Cleveland, Detroit and Chicago. At this time he became acquainted with Dr. Hurley and invested in the Grand Traverse Health Resort.

Sturm could never accept a sedentary domestic life. His entire adult life was spent traveling regionally for a few years, whereupon his wanderlust once again would take him far afield. In his younger years he had a reputation as a womanizer within the circles of other traveling men who encountered him, one calling him “a real Romeo, and perfectly reckless of female hearts.” It had been rumored that he had as many as three wives at one time, all in different cities.

He could never seem to stay in one place or with one woman for very long. Even in the later years of his life, the open road called, as he left his wife behind to run the hospital, taking to the road one more time to sell his herbal drugs. In fact, he was doing what he loved best on the day he died– setting out on an excursion as a traveling salesman.

Julie Schopieray is a regular contributor to Grand Traverse Journal.