The state of Michigan has a state flower: the apple blossom; it has a state bird: the American robin; it has a state wildflower: the Dwarf Lake Iris; it has a state gem: Lake Superior greenstone; it has a state stone: the Petoskey stone; and it has a state soil: Kalkaska sand.

Wait! A state soil? Who would care enough to advocate for a state soil? As a student of nature, I know that there can be only one answer—and correct me if I am wrong: a soil science class somewhere pushed state legislators for the adoption of Kalkaska sand as the state soil–and got the job done.

What of this Kalkaska sand, then? Besides a location where it is found, what more is to be said about it? Is it the soil that made this state rich in agriculture, the soil that grows soybeans, corn, potatoes, and fruit? Perhaps it is the rich mucky soil found around Kalamazoo that used to produce so much celery that the city was once called Celery City? Or, is it the fabled soil close to Michigan’s thumb with rich, black humus that goes down two feet or more?

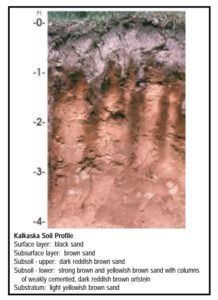

No, it is none of these things. Kalkaska is located in the pine barrens of Northern Michigan. It once grew white pine, red pine, jack pine, and a variety of oaks—and still does between logging operations. It generally does not grow crops successfully, especially those requiring moisture retention—like soybeans, for example. The parent material of Kalkaska sand, is, unsurprisingly, a coarse sand that let’s water percolate through easily. It dries out quickly between rains.

The parent material of a soil is made up of varying amounts of clay, silt, and sand, those particles graded in size from very small to quite coarse. A clayey soil—most common in Southern Michigan—contains microscopic grains that retain moisture well–while sand is gritty, unable to retain water; silt is somewhere in between. Soils that are most versatile contain fair measures of clay, silt, and sand: they are termed loamy soils.

In Northern Michigan a soil much prized for cultivation of many crops—corn through potatoes—is Emmet till, a loamy sand that takes on a reddish hue when moist. It is commonly found plastered upon the hills of the region, the glacial morraines that cover much of Leelanau and Benzie counties as well as other nearby places. When you take a handful of it, and squeeze, you get a gritty ball that sticks together, unlike Kalkaska sand that slithers through your fingers like dry sugar when compressed.

All of the soils in Northern Michigan—and in Michigan generally—are transported, in the sense that the glaciers brought down the parent material from the north. Elsewhere, as in the Southern states, soil developed from underlying rock layers as they weathered. Commonly, such soils are made of reddish clay that dries almost as hard as concrete in droughty summers. Root crops—like potatoes—and flowers like lilies—struggle under such conditions.

Emmet till naturally supports hardwood forests made up of Sugar Maple, Red Maple, North American beech, American basswood, White Ash (now gone), and Eastern Hemlock, while Kalkaska sand (and its related sandy relatives) grow pines and oaks. From the beginning, settlers to the area recognized the fact that hardwoods made better farms than pines. Many abandoned homesteads are to be found in the sandy barrens of Nothern Michigan, testimony to the difficulty of making a living on such unpromising soil.

So, why should Kalkaska sand achieve such recognition? My theory is this: the state tree of Michigan is the White Pine, and for good reason–it supported the logging industry that eventually tamed a vast Michigan wilderness. That being the case, then what soil grows white pines in abundance? You know the answer—Kalkaska sand.

For more information about the soils in Michigan, check out the soil surveys published by the US Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, available online.