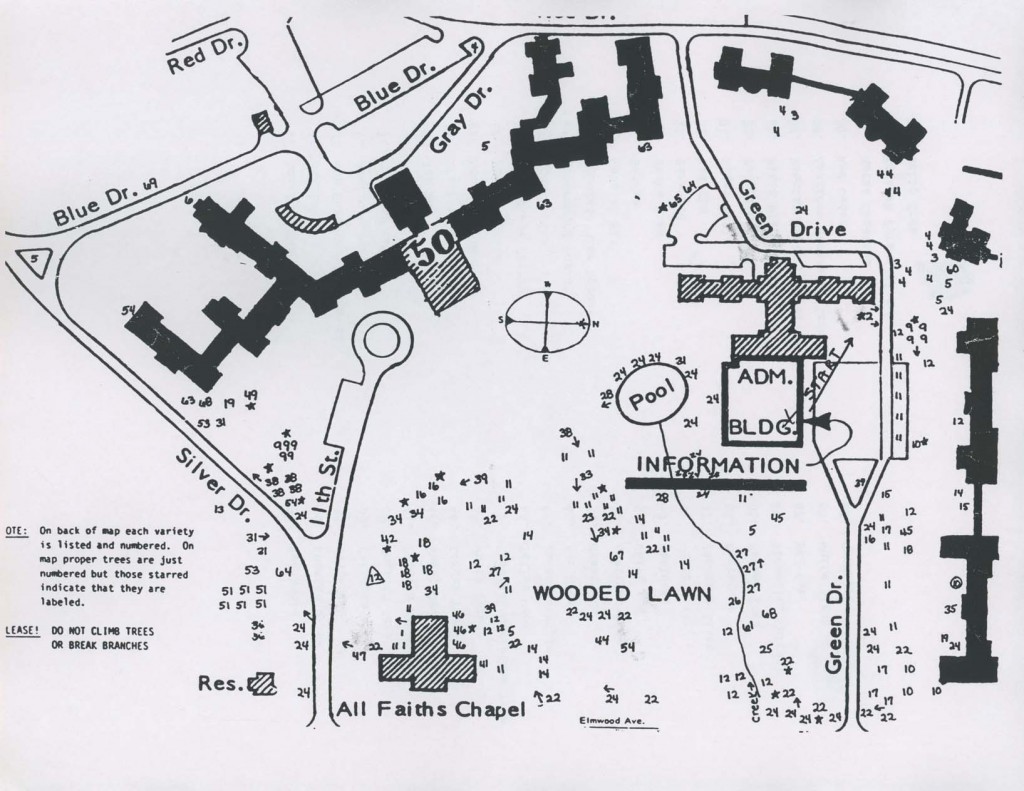

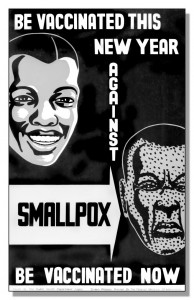

One hundred-fifteen years ago, smallpox was a serious and feared disease. Even though medical knowledge was much less advanced than it is today, it was known that the disease spread easily by close contact, and was carried on the clothing or bedding of an infected person. It would first present itself with symptoms similar to less serious diseases such as chicken pox or the flu. It was a horrible disease.: Symptoms of a typical smallpox infection began with a fever and lethargy about two weeks after exposure to the Variola virus. Headache, sore throat, and vomiting were common as well. In a few days, a raised rash appeared on the face and body, and sores formed inside the mouth, throat and nose. [Painful] fluid-filled pustules would develop and expand, in some cases joining together and covering large areas of skin. In about the third week of illness, scabs formed and separated from the skin… Most survivors had some degree of permanent scarring… (The History of Vaccines, The College of of Physicians of Philadelphia.)

Other results could be blindness, and loss of lip, ears and nose tissue. It’s no wonder near panic arose when the disease was discovered in the community. Because people were contagious before symptoms presented, family members and anyone who came in close contact with the infected person could become infected as well. Isolation was the best way to prevent further spread. When multiple people were found to be infected, it was common for them to be placed in a “pest house” where anyone with the disease would be brought, after which residents of the entire house were quarantined from the rest of the community. Location of those houses was a serious concern and most people were of the thinking, “not in my back yard!” City officials saw the necessity of these places to be available in the event of an outbreak, but fear of the disease spreading resulted in locating vacant homes well outside the city. One incident in 1904 occurred when a house on East State Street was chosen as a pest house for a man who had contracted smallpox. The evening he was brought to the residence, it was approached by a mob of people upset with the arrival of the disease on their street: The neighbors living near the house selected yesterday for a pest house turned out en masse last evening when the smallpox man was brought up to be put in the house, and made dire threats if the smallpox patient was put in the house….on the end of State street … It is some distance from any house but the neighborhood did not care to have it as they were not looking for the honors of having a pest house in their neighborhood. -Traverse City Evening Record 26 March 1904

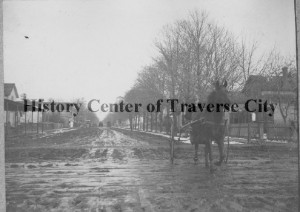

Traverse City was hit particularly hard by a smallpox outbreak over the winter of 1901-1902. In early November 1901, the first case for the season was reported and confirmed at the residence of Eugene Packard on Randolph Street. Unfortunately, before Mr. Packard started showing symptoms, about fifteen people had visited their home for a party, and were exposed. Those people were first quarantined in their own homes, but when a detention house was located, they all voluntarily went into isolation, even though none were showing symptoms. Eleven of the fourteen were between the ages of 14 and 21. Mrs. Paul Lehman served the “party” as chaperone and cook. A few days after arriving at the Zeigler house, an article appeared in the paper titled “SEA SERPENT COTTAGE”. It described the situation in this particular “pest house”:

Life among those who have been exposed to the smallpox and who are consequently confined in the detention home on the bay shore, is neither slow nor monotonous. The fourteen people who are for the present isolated from the rest of the city, are making things as pleasant as possible for themselves as they can. The Zeigler house in which they are residing at present, has three good sized rooms below, and one large room above. The ladies of the party sleep above, where there are four beds. The gentlemen of the party sleep in a room below. The kitchen where Mrs. Layman presides, the oysters, chicken and beef that have formed the staple diet of the inmates of the house since they went there, are prepared for the table, and thus far there has been no difficulty in disposing of large quantities of the provisions. All the inmates of “Sea Serpent Cottage” seem to be as happy as possible under the circumstances. It is said that there has not been a tear shed since the cottage was opened…Fishing, boating and hunting occupy the attention of the boys out doors, and inside, cards, dancing, music and literary pursuits are indulged in. By long odds the most remarkable thing that has occurred since the party went out there is the capture of a sea serpent which would put to shame any creature of a similar kind that Petoskey ever saw or heard or dreamed of. The creature was captured, so the inmates of the home claim, through the bravery of Joe Ehrenberger. He was out for a stroll on the bay shore when he came upon the huge creature asleep in the surf. He secured a hawser, and stealing up almost into the jaws of the beast, managed to get the rope about the neck of the serpent, and took two half hitches and a round turn about a tree. Then the other men of the party came to his aid a team of horses was secured, and the creature was hauled ashore, and hitched to a fence post in the front yard. It seems rather sluggish from the cold, and is not so active as at first. The boys are teaching him several tricks, with which they hope to entertain their guests. The girls try to flirt with the serpent… but he does not approve of it, and when he points his horns at them, they retreat into the house. The serpent is described as being of great size, though his exact dimensions have not yet been ascertained. He has two heads, and two eyes. His ears are like that an elephant’s and his tail like the rudder of a boat. The inmates of “Sea Serpent Cottage” are preparing to have a photograph taken of the creature, which they will send to their friends in the city by the Citizens Telephone line, so as to avoid all danger of contagion. –Traverse City Evening Record, 18 November 1901

On November 20, a “card of thanks” was posted in the newspaper, thanking Mr. Wheeler of the Citizens Telephone Co., for providing the house with a telephone free of charge. In another ad, they thanked their friends and family for their support and “Dr. Ashton for furnishing marshmallows, oysters and other goodies that we all so much enjoyed” and signed “Guests at Sea Serpent Cottage.” As it turned out, none of the people confined to Sea Serpent Cottage were infected and their three week adventure ended. This situation was probably the most pleasant experience of any of those quarantined over the next few months. Eugene Packard slowly recovered from his case of smallpox never knowing how he had become infected. His confinement and recovery lasted over a month. As was common practice, everything in the room where he was confined was burned– bedding, clothing, furniture and curtains, and the ashes buried. Then “the house was subjected time and again to the most thorough fumigation and other disinfecting processes.” –Traverse City Evening Record, 3 December 1901

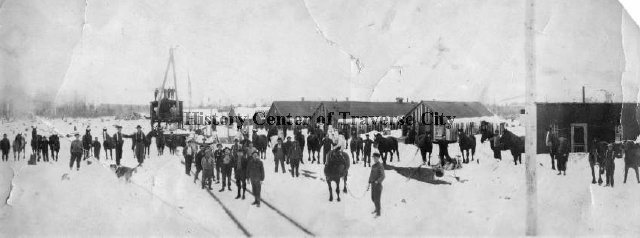

Meanwhile, a less pleasant situation arose in the village of Interlochen. A man arrived into town from a lumber camp somewhere in Wexford County to the south, and had been in the community for about two weeks before his smallpox diagnosis. He was quickly isolated at the town hall, then to another location near the depot. At the camp where he had been working, seven more men had become infected and when the 55-man crew were first told they were to be confined to the camp, “they became almost furious and threatened to break out of quarantine…for they did not propose to be quartered where there was no possibility of their escape from the disease” (Traverse City Evening Record, 16 November 1901.) The local health officer, advised by Dr. Swanton, decided that they should get only the men with confirmed cases removed and isolated. The townspeople were not happy with the location of the pest house which they felt was too close to the train depot: “It is said that there was very strenuous objection to this, and that there came near being a riot before the men were safely in the new pest house.” Railroad service in and out of Interlochen was even shut down. Things quieted down a bit once the city attorney and the health officer made some decisions to help ease the fears of the village. The man assigned to be the local health officer “has had such an opinion of the intensity of the feeling against bringing the victims of the disease to the town that he has gone armed all the time till yesterday” –Traverse City Evening Record, 5 December 1901.

Two weeks later, the patients were relocated to a house a half mile out of town. “All apprehension on the part of the inhabitants of the village lest the disease should spread in the village itself are allayed. The pest house is guarded all day and night to prevent inmates from escaping, and a feeling of security pervades the village” (Traverse City Evening Record, 26 December 1901). In total, there were ten cases in Interlochen. All recovered.

In late January 1902, a case of smallpox was identified at The Northern Michigan Asylum. The physicians began a round of vaccinations, isolated all who had been in contact with the first victim, and the entire Asylum was put into quarantine– patients and staff alike. Toward the end of the five weeks of quarantine, a few merchants began to feel the effect. Some complained about the amount of business lost due to the closing of the asylum: “some three hundred persons connected [with the asylum]…draw salaries and spend their money here…The situation affords an illustration of the value of the asylum to this city, and shows also the value of about $10,000 a month circulated in the city by asylum people….” When the quarantine was finally lifted on March 1, 1902, “all who could possibly get away were down town this afternoon, and they were greeted with almost as much enthusiasm as though they had been away on a long journey” (Traverse City Evening Record, 1 March 1902.) In all, thirty one cases of smallpox were confirmed at the asylum. All were mild and everyone recovered.

Statistics for the state of Michigan revealed that in 1901, 27 people died from small pox . In 1902, out of 7086 cases state wide, 42 people died. Traverse City was fortunate. Only two were recorded as having died as a result of their symptoms during this time period. One was a four-year-old girl in Williamsburg, and the other, a man at Bates. Vaccinations were available and highly recommended but usually only administered when the threat of the disease came into town.

We are fortunate to live in a time when vaccines prevent these horrible diseases that plagued our ancestors. Smallpox was globally eradicated by 1977.

Julie Schopieray is a regular contributor to Grand Traverse Journal, as well as an author of works on local history.