Librarians love to keep records. Sure, we enjoy reading, assisting patrons, and honing our collections to perfection. But our true passion is in organizing, and that starts by keeping good records. From the dawn of the profession, librarians knew one thing: “If I can keep a record of it, it’s worth recording.” And Alice Wait, at the dawn of her personal professional career, swallowed this librarianish platitude hook, line, and sinker.

Alice was a librarian’s librarian, to be sure. The records she kept while she was THE librarian of Traverse City Public Library (1906-1950) speaks to her recordkeeping prowess. (We know she wasn’t there for the pay. Local historian Richard Fidler’s research into the City records revealed that Alice was paid less than the building janitor (Glimpses, p. 54)).

Some of you are saying, “Prowess? Really? To keep a list of books?Phhhbt.” I’m not saying it’s a miracle of engineering, creating and maintaining a library collection (what we professionals like to call “Collection Development”), but just think of all the factors involved! Each book is carefully weighed and measured: What are patrons looking to read? Are there other books patrons need to read that I might need to foist on them? What’s the opportunity cost here (or, what can’t I purchase because I’m buying this book)? What’s the drain on my budget and shelf space? Do I already have other, similar titles (or the same title) in the collection? Have I exhausted all of my materials resources and reviews to make sure I’m getting the best of the best?

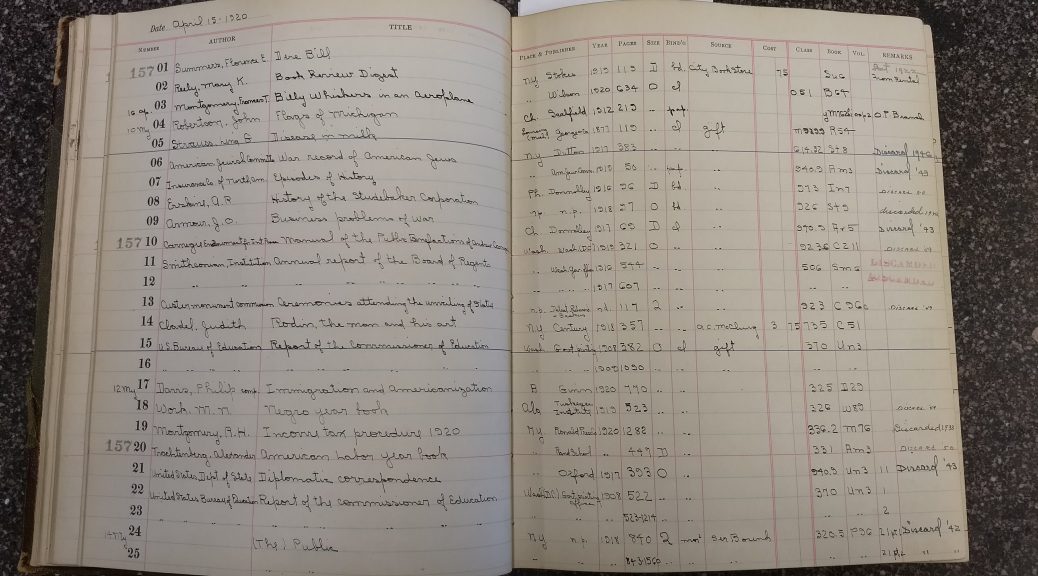

Join me in looking at the Accessions record for Traverse City Public Library (TCPL), 1919-1925. First, it’s a beautiful volume: tight spine, no leather rust, and I bet this is pre-war paper… no acid yellowing, and the lignin fibers, well, let’s just say they should probably have their own fashion line. Rowr!

Join me in looking at the Accessions record for Traverse City Public Library (TCPL), 1919-1925. First, it’s a beautiful volume: tight spine, no leather rust, and I bet this is pre-war paper… no acid yellowing, and the lignin fibers, well, let’s just say they should probably have their own fashion line. Rowr!

That the volume is in excellent condition, and that we still have it, tells us how important these types of records are to a library. But it’s the contents, handwritten in Alice’s tight, neat script, that tells us a story of a community, not just a library in a vacuum.

So what were Traverse City folk reading in the Roaring Twenties? Taking into account the effects of the Great War in general (a dip in the young male population, rise in women in the workforce, the doubling of the nation’s total wealth), people were frankly reading a lot of popular fiction. One of Alice’s most-used wholesalers, A.C. McClurg out of Chicago, also published a lot of escapist and science fiction literature, including Edgar Rice Burroughs (of “Tarzan” and “John Carter of Mars” fame). Yes, Burroughs was definitely on the shelves at TCPL.

This is not a huge revelation, but it does speak to a trend in our local library. In 1905, the TCPL published its circulation figures in the Grand Traverse Herald, revealing that 90% of items checked out by both adults and children were fiction titles. We can’t get those figures from the Accession records, but we do know what was present in the collection, and from a cursory read, fiction and periodicals made up the bulk of purchases. With today’s technology, Traverse Area District Library (TADL) can provide the public with up-to-the-minute stats using our Statistics Dashboard. Again, we don’t know from these stats what is fiction and nonfiction, but anecdotally, I’ll attest to the fact that Grand Traverse County still likes its fiction.

This is not a huge revelation, but it does speak to a trend in our local library. In 1905, the TCPL published its circulation figures in the Grand Traverse Herald, revealing that 90% of items checked out by both adults and children were fiction titles. We can’t get those figures from the Accession records, but we do know what was present in the collection, and from a cursory read, fiction and periodicals made up the bulk of purchases. With today’s technology, Traverse Area District Library (TADL) can provide the public with up-to-the-minute stats using our Statistics Dashboard. Again, we don’t know from these stats what is fiction and nonfiction, but anecdotally, I’ll attest to the fact that Grand Traverse County still likes its fiction.

Alice did a solid job of keeping up with what was popular in the world, considering how removed Traverse City feels. She purchased the drama “All God’s Chillun Got Wings,” by Eugene O’Neill, the week it came out (January 8, 1924), even though Time magazine didn’t publish a review until March of the same year. Same with Sinclair Lewis’ Arrowsmith, which won him the Pulitzer Prize in 1926.

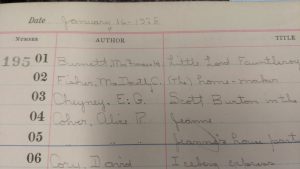

She also purchased works of local interest, such as Traverse City novelist and scriptwriter Harold Titus’ 1922 novel, Timber. She purchased (and often replaced) works that would have been classics in her time, including Frances H. Burnett’s Little Lord Fauntleroy (1886). I do wish she had kept in these records the prices of these volumes, but alas. We do know that she supported the local economy, as a good 60 percent of her purchases were made at the City Book Store (managed by Dean E. Hobart, at 220 E. Front Street).

Here’s something wild that might be unique to Alice’s recordkeeping. She may not have thought anything of it at the time, but for every author that was a married woman, Alice would give her the title “Mrs.” So, Burnett’s entry looks like “Burnett, Mrs. Frances H.” But, she excluded all other titles. Dr. Mabel Elliott’s Beginning Again at Ararat, she’s just plain old “Elliott, Mabel,” to Alice. I have no explanation for this, it’s just curious. Perhaps Alice did not have an ingrained bias for feminism.

Some of the periodicals Alice subscribed to in 1921 are still in print today (Century, Atlantic Monthly, Forum, Good Housekeeping, Harper’s Magazine), while others are long gone (Everybody’s Magazine, Little Folks). I can tell you with all certainty that every issue Alice purchased is long gone, as the last column for each accession indicates when the item was deaccessioned from the collection. There must’ve been a huge weed in 1944, as Alice discarded whole pages of accessions that year in periodicals. What a joy for Alice, to “close the book” on all those records at once! (Librarians like librarian puns almost as much as recordkeeping.)

Alice was probably the first and last person to write in this volume. When she retired in 1950, this volume likely went into retirement with her. How did they keep records after Alice is a mystery, as those records did not survive to the present. Unfortunately, librarians one hundred years from now will likely lament the same concerning our generation of recordkeeping. Thanks to Alice, though, that small slice of time she covered reveals a whole lot about Traverse City and its readers in the 1920s.