by Julie Schopieray

Unless you are already aware of its existence, or happen to pull off the highway on a little side road that was once a part of the old highway, you’d never know it was there. A small gravestone stands alone under a large pine tree, just off US-31 near the ghost town of Yuba in Acme township, Grand Traverse County. It belongs to two-year- old William Leith, who died in February 1859.

This lone little grave has stirred much curiosity, including mine. Its solitary status has led to assumptions about its origin, which has resulted in stories designed explain it . After seeing this gravestone, I too wanted to know about it.

Starting with just an internet search, I found one author who reported that this was “the oldest known Caucasian grave in the northwestern region of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula.” Another website gave an account of the family traveling in a wagon train through the area when their son became sick and died. They buried him along the road and even with their grief, had to continue on their journey.

This particular tale raised the question: Why would anyone be traveling in a wagon train in Northern Michigan in the middle of the winter? It did not seem likely.

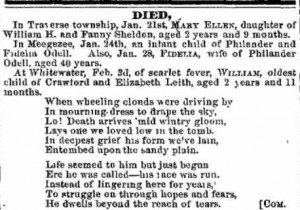

My next step was to search digitized issues of the Grand Traverse Herald. The search brought up three hits with the name Leith. The first was from Dec. 1858, which described a very large chicken belonging to Mr. Crawford Leith, a resident of Whitewater. The second was an obituary for William Leith, the son of Crawford and Elizabeth Leith, who died of scarlet fever. The date matched the gravestone exactly. (The third hit was in April, 1859 with election results mentioning Mr. Leith running for commissioner of highways—he lost the election).

My curiosity then took me to the county deeds office to check just where this family lived. I knew that in 1859, this area of the county at Yuba was still called Whitewater. My first thought was that when Willie died, he was buried on their own property, which was a common practice at the time, especially since there was no established cemetery nearby. [The Yuba cemetery, across the highway from this grave, wasn’t established until 1904.]

Vincent Crawford Leith purchased 160 acres in Section 26 of what is now Acme Township. The dates on the land records were a bit confusing. The land grant was dated 15 August 1862, but on the very next page of the liber was a warranty deed where Mr. Leith sold this same property to a Mr. Price in Aug. 1859. It may be that the transaction took place much earlier, but was just not recorded until 1862.

Strangely, the spot where Willie is buried is not the property the Leiths owned. Since Willie died in the winter, a burial may have been delayed until the spring.

Now I had more questions than answers: What did they do with his body until the ground thawed? When the Leiths moved to Ohio later that year, did they have someone place the stone for them, and if so, did those people put the stone on the wrong spot? Why would Willie be buried on property they didn’t own and so near the road?

A thorough search of the 1860 Federal Census shows no sign of Mr. Leith or his family, although I suspect they moved to Allen County, Ohio after their property was sold in 1859. They may have been traveling during the census, and were not counted.

Mr. Leith volunteered and served as a musician in the 118th Ohio Infantry from September 1862, until the end of the Civil War. They spent the next 45 years in Allen County, Ohio. Basic genealogical research shows that this is indeed Willie’s family.

There is a romantic feel to the legends that have evolved around this stone. The statement that it is the oldest known grave in the region may be true. It can be documented that others died in the area before this, but grave locations are either unknown, unrecorded, or were later moved.

The reason for the location of the solitary little grave remains unanswered. The truth however, is that this little boy’s family were area residents for a few years, not just passing through. The fact that the child is separated from the rest of his family, is a reality which pulls at the heartstrings of those who see the stone. The little boy’s resting place has been lovingly cared for over the years. The stone has been broken in several spots, but an anonymous person has made a gallant effort to cement the fragments together to keep it in one piece. Artificial flowers and small trinkets surround the stone, left by kind-hearted, nameless visitors.

Julie Schopieray is a local author and history buff, who enjoys debunking local historical myths.