by Claribel (Wilhelm) Dugal Putnam (1893-1987)

These memoirs were written to Claribel’s granddaughter, Virginia LeClaire, in 1977. Claribel died May 27, 1987 at the age of 94. She is buried next to her husband and daughter in Oakwood Catholic Cemetery.

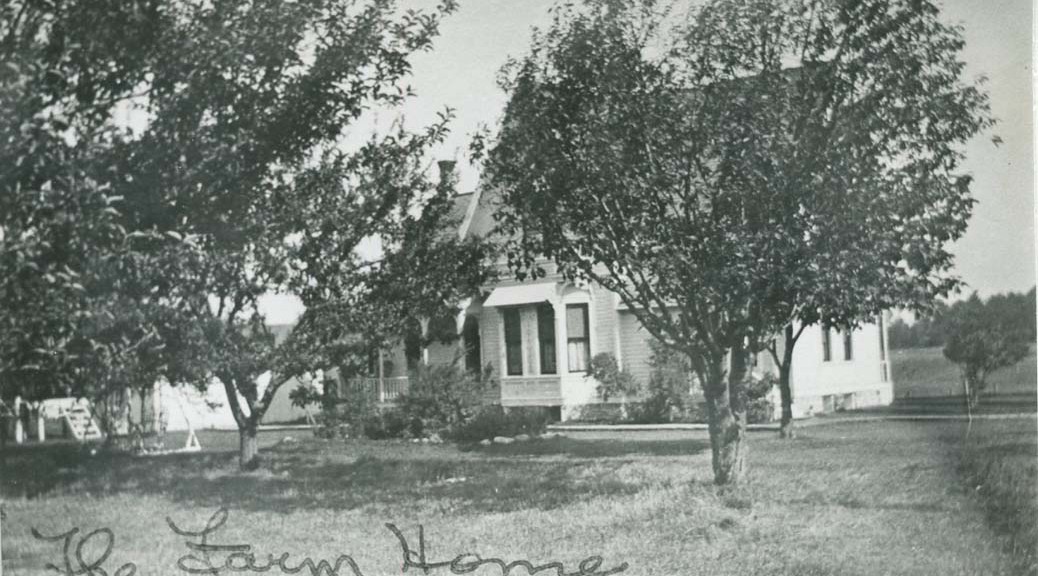

I was born May 15, 1893 on the family farm in Grand Traverse County. My father, Joseph Emanuel Wilhelm, was several years older than my mother, Rose Zimmerman. He had made himself very well-to-do in the wholesale lumber business prior to their marriage. He built the farm house in Garfield township and took my mother there as his bride in 1885. It was called “Pleasant Valley Farm” and was located on U.S. 37 South near McRae Hill. (There is a trailer park there today.)

The house was rather elegant for the times with a vestibule facing the driveway, parlor, sitting room with a curved alcove of windows facing the flower gardens, large dining room, kitchen, summer kitchen, huge pantry, and five bedrooms. A rear entrance led to a large wood-covered space. Across this space was a three part building which housed a room for storing wood for the kitchen stove, the milk room where milk was separated for cream, and the ice house where in February the men cut blocks of ice from nearby Silver Lake and packed them with sawdust for summer use. A hired man put one block in the ice box each morning and it was one of my duties to see that the pan under the ice box was emptied once each day – otherwise it would run over on the floor. Occasionally I forgot and suffered the consequences! There was a large bell outside of the back door, near the windmill, mounted on a large wooden pole. It was used to call the men from the fields for dinner and supper.

Our basement was full of wood for the hot-air furnace. The wood was cut from our own woods each fall. However, there was no plumbing and no electricity. On a shelf in the kitchen were eight kerosene lamps. Each day we filled them with oil, trimmed the wicks, and washed the glass globes. In addition, there was a lamp over the dining room table, one in the sitting room, and a table lamp in the parlor, all of which had to be cared for regularly. Of course, we had the necessary little house “out back.” It was there, surrounded by lilac bushes. There were two grownup seats and one little low one for small folks. We had the usual accessory: the Sears & Roebuck catalog.

In the kitchen, we had an iron sink with a pump which we used to obtain water for cleaning and washing. The drinking water had to be brought in from outside where we had the windmill and another pump. The first windmill was a wooden structure and I remember when it was replaced with a steel frame. We were so very proud of it. On one kitchen wall was a bench for the pails of drinking water. Hired men kept these filled.

Although there was a table in the kitchen, we always ate our meals in the big dining room. My mother was a fine cook and housekeeper. She never had a loaf of baker’s bread in the house. She made bread twice weekly and every day she baked goodies. She had learned from the Wilhelms how to make their famous kolaches and we were never without pies, cookies, donuts, and cakes all made, of course, from scratch.

My mother was unusually kind and good natured with an over abundance of patience, so we children were never punished severely. I can’t remember that I ever was spanked or slapped and I wasn’t a model child by any means. I remember my father only as a sick man in a big chair. During his final days, we were sent to our Zimmerman grandparents to stay. One Sunday, Uncle George Fritz decided to take us home for a visit. As we drove over McRae Hill, we met Dr. Julius Wilhelm with his horse and carriage. “It’s all over” he said. Of course, we wanted to know what was over. Uncle George told us: “Your mother will tell you when you see her.”

Mother wished to keep the farm for my brother William, so her four brothers found a good man to act as superintendent. That good man was William Henry Gravell. He was a bachelor, and eventually he and Rose were married. I was only six when my natural father had died in 1900, and “Grandpa Gravell” was wonderful to us all.

I remember when Rural Free Delivery came our way. Our first mailman was a bachelor, Mr. Gilbert, who drove a horse and buggy. We were always sitting by the mailbox, on a post, waiting for him. We had mail every day except holidays and Sundays. Our first telephone was really an event. It was on a slab of oak and we had to “ring for central.” There were several families on a line – sometimes as many as ten. We never had a radio, that came after I was married, but we did have an Edison phonograph with cylinder disks. We thought it was wonderful, and it was! I remember the first automobile I ever saw. One day I was out in the yard and I saw a car enclosed in glass! I rushed in to tell mother and she said that it just couldn’t be. When the weekly newspaper came out, it told of a wealthy Chicago man who had driven through town on his way to his summer home in Petoskey. It described the car as being enclosed in glass and was called a “sedan.”

We tapped the maple trees in the spring and had maple sugar parties. The juice had to be boiled on the cook stove for a long time, then we dropped it on a cake of ice and it hardened, making it like candy. Every Sunday in nice weather we made a five gallon freezer of ice cream. It was so good – made of real cream, beaten eggs, sugar, and vanilla. The freezer was packed in layers of ice and salt and the melted water ran out of a hole on the side of the freezer, so it had to be made outdoors. We took turns rotating the paddles until the ice cream had turned solid. Once a year, in late fall, we made sauerkraut. We used wash tubs with large cutters to slice the cabbage, put it in a barrel close to the hot-air furnace, and then left it to “work.” When it was thoroughly “ripened” mother put it in glass jars.

Washing was always and only done on Monday. We did the washing on the back platform in summer and in the kitchen in winter. We had tin tubs, used washboards, and boiled everything except colored clothes. We also starched many things, including ruffled petticoats, and then hung them on a clothes reel to dry. Ironing was a big task in those days. Irons came in groups of three different sizes. There was a handle that clamped over the tops of the irons. You used an iron until it got cold and then you went to the wood stove and exchanged it for a hot one.

Gathering eggs and bringing the cows up to the barn to be milked each night was a job for sister Mabel and myself. We took turns, but when the hens were “setting” in the spring, they were very angry when we reached in for the eggs and would peck at our hands. It hurt and I cried, so Mabel did the full job in “setting time” and I took the dog and rounded up the cattle.

Saturday was bath day. Children had to bathe in the afternoon so the grownups could have the kitchen for their baths at night. We had a round tub and you stood up unless you were small enough to sit down. Hot water came from the reservoir on the side of the kitchen stove. When you used any water from this hot water tank, you must replace it so it would be warm for the next bather. Daily baths were something of which we had never heard.

I couldn’t tell you about life on the farm without telling you about our driving horse, Billy. We raised farm horses, but a driving horse was “something else.” We had a rubber-tired open carriage which was the latest word in elegance, but we used this only for Sundays and trips to the city to exchange our butter and eggs into groceries. For every day fun we had a two seated sort of light wagon which held a lot of youngsters. When we came to McRae Hill, Billy would stop and we would walk up the hill. When he got to the top, he would stop and wait for us to get back in the wagon. We loved that horse! When he got old and sick, Grandpa Gravell decided he should be taken out of his misery. The only way at that time was to shoot him. He couldn’t bring himself to do it, so he hired a neighbor. When the day came, he was so afraid that the man wouldn’t kill Billy instantly, that he did it himself. We all had a bad day that day.

It was a mile walk to the one-room school house. Grandpa Gravell took us in wintertime with the horses and sled, but in good weather we walked. There were eight grades and one teacher. Often the teacher boarded at our house. We carried our lunch in a tin pail. There was a wood burning stove for heat and of course, “rest rooms” were outside. At recess time we played “Anti-I-Over the Woodshed”and had lots of fun. A pail of water with a dipper was at the front door. We had never heard of “germs”!

When we finished eight grades of country school, we were required to take an examination at the court house in Traverse City. It was a written exam and if I live to 100, I will never forget how frightened I was. You needed to pass this test in order to progress in your education. My poor older brother William had gone through all of this. In fall he drove a horse into the city to start his freshman year of high school. He came home on Friday night feeling badly and we thought it was because he was so scared of a new school. However, on Saturday he was feeling worse. Sunday he went into a diabetic coma and died that night. He was 14. William was a good big brother to me. I remember one time when I picked the raisins out of the middle of my mother’s cookies. She said I had to eat all of the cookies. I didn’t like them so I sneaked them out to William and he ate every single one of them for me.

I want you to know that my experiences on the farm were all pleasant ones. I had a wonderful time as a child and it has been a pleasure to think of many of those happy days as I have written them down for you. No wonder I have lived to a ripe old age when I got such a good start on the farm home.

Thank you to Virginia LeClaire, local author and historian, for providing her grandmother’s memories for all of us to share. LeClaire is author of the popular local work, “The Traverse City State Hospital Training School for Nurses,” available at local retailers and Amazon.com. She is currently working on a history of the Federated Women’s Clubs of Traverse City.