by Julie Schopieray, author and avid researcher

Medicine was in her blood. The daughter of a Civil War surgeon, Sara Thomasina Chase was the first-born child of Dr. Milton Chase who settled in Otsego, Allegan County, Michigan, after the war. Giving his children a good education after finishing her secondary schooling in Otsego, Sara entered the Ypsilanti Normal School. She graduated in 1891, then taking a position at the Traverse City High School teaching English and science. Teaching until 1896, she decided to follow in her father’s footsteps and entered medical school at the University of Michigan. After her graduation in 1900 at the age of 34, she went back to Otsego and practiced with her father. In 1906, she returned to Traverse City, taking over the office of her cousin, Dr. Oscar E. Chase, while he went back to the University of Michigan for more training. She set up office in the State Bank building where she advertised her practice.

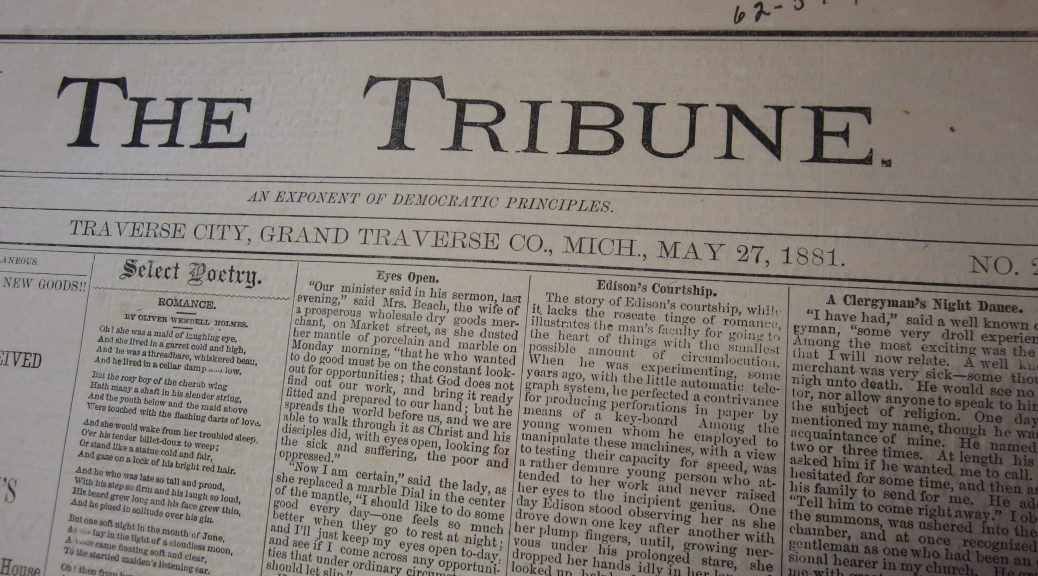

This 1903 article from the Traverse City Evening Record gives us a glimpse of her ambition and dedication to the practice of medicine as a woman in a man’s world.

Dr. Chase entirely disapproves the old idea, which once was quite prevalent, that a professional woman could not be a womanly woman. She is a physician of no mean ability, and has considerable skill with the needle. She is thoroughly accomplished in household science. She is very fond of outdoor exercise, being an especially fine horsewoman. Still they are outside interests to her, after all, as her heart is in her profession, and it is this that receives first and best thought. [TCER 15 May 1903]

Known to be as good a physician as her male counterparts, she was be able to handle just about any situation. In 1908 she traveled five miles past the village of Cedar in a blizzard to tend to a patient. The Traverse City Record Eagle reported, “Dr. Sarah T. Chase has a hard trip yesterday afternoon, driving five miles beyond Cedar in the blizzard. She went to Cedar on the train and was met there by a driver. Ten miles in such a storm required nerve even in a man.” (7 Feb. 1908)

Always wanting to improve her skills, in the summer of 1909 she took a six-week break from her practice and attended a special summer school course at U. of M.

Active with the Congregational Church, she served as Sunday School teacher. She often gave lectures on children’s and women’s health at events of the Woman’s Club and Central Mother’s Club. Her lectures were about topics important to the women of Traverse City and covered subjects such as the proper feeding of children and babies and “What to do Until the Doctor Comes,” a lecture about first aid. As chairman for the public health committee for Grand Traverse County, she often gave talks about various health topics relevant to all citizens: “The Air We Breathe and the Value of Ventilation,” “Children’s Diseases,” “Suppression of Tuberculosis” as well as sensitive women’s health topics, such as “Sex Hygiene,” and “The Responsibility of Girlhood to Womanhood.” The notice for the last talk stated: “No men will be admitted to this lecture.”

Not content just to maintain her practice—or to be pigeon-holed into women’s care only—she became involved in local health-related issues that mattered to the entire community. In 1911 she was instrumental in petitioning the state to pass a bill “requiring licenses for the sale of patent and proprietary medicines by itinerant vendors.” In simple terms, the bill would require licenses for traveling elixir salesmen. She served as meat and milk inspector for the city and reported to the city on sanitary inspections of farms and slaughter houses. As part of her county responsibilities, she acted as secretary for the county Tuberculosis Society. Dr. Chase was one of the first woman members of the Grand Traverse County Medical Society. In 1907 she accepted the position of secretary of the Society when her associate, Dr. Myrtelle M. Canavan, left for Boston after her husband’s death. She was also a member of the Michigan State Medical Society and a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution (D.A.R.).

Tuberculosis hit Traverse City hard in 1915. Dr. Chase worked tirelessly as head of the board of the Anti-Tuberculosis Society, a group she helped found. That organization aimed to improve health conditions by working with others in the medical field and offering free clinics in the city to educate the public about the dreaded disease. She used experimental treatments, publishing her positive results in the American Journal of Clinical Medicine.

In 1920 she accepted a job at the Kalamazoo State Hospital as assistant physician, where she worked until 1922, moving to Port Huron and taking the position of “Great Medical Examiner of the Ladies of the Maccabees”, a post she held for the next seven years. She assisted with Maccabees clinics for children and was on the board of the Anti-TB Association.

While in Port Huron, she was reacquainted with Harlow Willson, whom she likely knew as a young girl in Otsego. He had been living in Boyne City with his wife Maybell and their children, working as a postman. After the two were divorced in 1924, Dr. Chase and Harlow were married in May, 1926.

A progressive woman, she did not give up her maiden name, instead preferring to use a hyphenated name: Dr. Sara T. Chase-Willson. They were both sixty years old at the time of their marriage– her first and his second. After their marriage, Harlow and his mother ran Willson’s Garden shop on River Road, while Sara worked for the Ladies of the Maccabees.

During her years in Port Huron, Dr. Chase was actively involved in the Ladies Library Association, fought for child labor laws, and served as an active member of the Ottawawa Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (D.A.R). She was a committed member of the Theosophical Society, and, as an expert in that movement, gave speeches on the history of Theosophy. In 1929 she resigned from her position with the Maccabees, but remained active in medical causes.

Around 1941 she and her husband moved to Boyne City where they opened another garden shop and florist business. In 1946 Dr. Chase fell in their home and broke her hip, but fully recovered and continued her volunteer work. After her husband’s death in 1950, she sold her Boyne City home and retired to the Maccabee Home in Alma where she died three years later at the age of 87.

___________________________________________________________________

It was unusual for a town the size of Traverse City in the early 1900s to have two female physicians. Sara Chase was not the town’s first woman doctor, but she and Dr. Augusta Rosenthal-Thompson each had tirelessly worked serving the people of Traverse City. Their careers only overlapped by a few years toward the end of Dr. Rosenthal-Thompson’s time in the city, but these two pioneers of medicine– amazing women in their own ways–each had an impact in the community, paving the way by their influence and demonstrating that women could successfully work in a career dominated by men.

You can read more about Dr. Rosenthal-Thompson in the book Who We Were, What We Did, by Richard Fidler.

Julie Schopieray is a regular contributor to Grand Traverse Journal. She is currently working on a biography and architectural history of Jens C. Petersen, once a Traverse City-based architect, who made his mark on many cities in Northern Michigan and California.

“The Dennos Museum Center – 25 Years and Growing,” talk delivered by Eugene Jenneman to the OMPHS

“The Dennos Museum Center – 25 Years and Growing,” talk delivered by Eugene Jenneman to the OMPHS

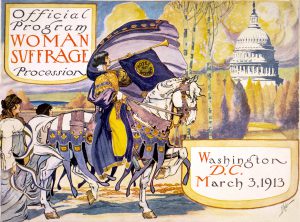

Women’s History Project hosts program on “Reliving the Women’s March”

Women’s History Project hosts program on “Reliving the Women’s March”