by S.A. McFerran, B.A. Environmental Studies, Antioch University

Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette recently weighed in on aquaculture. His opinion is that aquaculture would subordinate public uses of open waters in favor of private control.

The open waters of Lake Michigan have been used for commercial purposes in the past and are currently used for commercial purposes. Aquaculture is a commercial use, as are marinas and trap nets already in common usage by commercial fishermen. Trap nets are set in the Spring and often remain on the lake bottom until fall. They are checked regularly and the fish are sorted and the nets returned to the lake bottom. A net pen for aquaculture is similar and like a trap net would not interfere with public use of open waters. With proper siting, scale and monitoring, pollution is minimal. (1)

What tools do the architects of an ecosystem have? Add species, subtract species (as with the sea lamprey), improve habitat and change goals. Fishery departments know a lot about the limnology of the lakes. Using that knowledge, places favorable to aquaculture could be identified. Limited operation could be allowed in those places.

A worthy goal is the local production of fish by Michigan citizens in Michigan waters. Just as enthusiastic farmers sell vegetables at local markets, small aquaculture operations could offer fresh local fish at market. Large corporate fish operations should not be the goal. The goal is a citizen-led entrepreneurial process that allows aquaculture on a local basis.

If government is making a determination on how many fish can be raised in the Great Lakes, it would be informative to know what the historic population of fish was. It is clear to anyone reading historic accounts of fishing in the Great Lakes that the population of fish was, in the past, much greater than it is now. In 1872, 39 million pounds of fish was taken. The total fish population was more than twice the present populations. (2) That alone puts to rest the argument against the resiliency of the Lakes.

Additionally, other technical problems of aquaculture can be solved in Michigan as they are being solved in the rest of the world. (3) The State of Michigan has learned a lot about how to operate aquaculture in places like Platte River. That hatchery was once a big polluter of Platte Lake but they cleaned it up and now raise millions of fish pollution free.

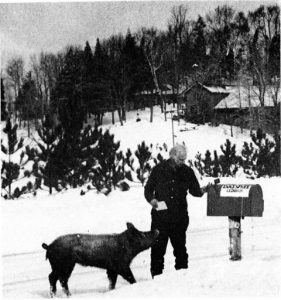

Another local success story concerns Harrietta Hills Trout Farm LLC, on the AuSable River, which has operated for five years without incident. The Department of Environmental Quality issued a permit for the farm that holds the operators to high standards which “requires weekly monitoring for phosphorus, which cannot, on a seasonal average basis, exceed 15 parts-per-billion in the 8.64 million gallons-per-day”. (4)

Ecosystems are complex. In recent history, marketing the experience of catching fish, and sport fishing in general, has subordinated any other possible use of the Lakes, including aquaculture. Both have a place in the Lakes. The Waters held in “public trust” are held for all the “public,” not just sports fishermen.

S.A. McFerran

B.A. Environmental Studies, Antioch University

Platte River, Michigan

(1) Diana, Jim, quoted from personal correspondence with the author, February 2017. Dr. Jim Diana is Director for Michigan Sea Grant, and is involved in leading the statewide program in its research, education and outreach efforts on critical Great Lakes issues, such as sustainable coastal development and fisheries. When asked about pollution issues, specifically if Aquaculture pens can be operated without polluting the Lakes, his response was: “Absolutely. There are 11 licensed operations in Lake Huron on the Canadian side, and no damages have been determined from them as of recently. There was a problem in one area, with nutrient addition causing some algal blooms, but they moved to another location and all has been fine since.”

(2) Bogue, M.L. Fishing the Great Lakes – An Environmental History. University of Wisconsin Press, 2000.

(3) “On January 11, NOAA published a final rule implementing our nation’s first regional regulatory program for offshore aquaculture in federal waters. In doing so, NOAA is expanding opportunities for U.S. seafood farming in the open ocean. NOAA and our partners are working to advance and expand U.S. aquaculture.” NOAA Fisheries. “NOAA Expands Opportunities for U.S. Aquaculture.” Accessed March 20, 2016. http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/

(4) Ellison, Garret. “In battle over Holy Waters, anglers put Michigan fish farming on trial.” M-Live. Accessed February 04, 2016. http://www.mlive.com/news/