by S. A. McFerran

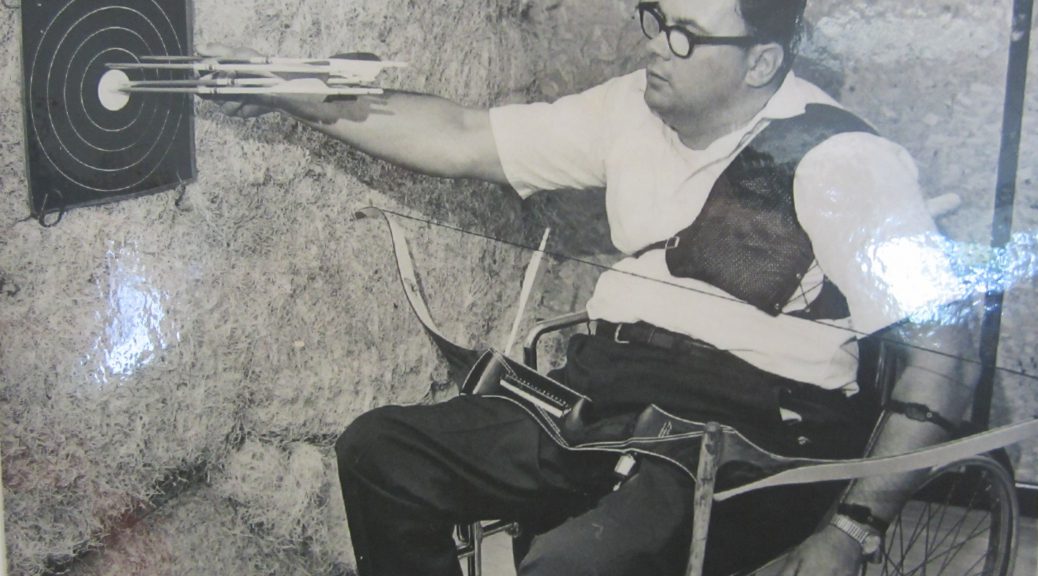

Many school groups from Traverse City and Leelanau traveled to Innisfree, a camp for environmental education, on Pyramid Point within the Sleeping Bear National Lakeshore. The program operated year-round within sight of the Manitou Passage, and the fifth- and sixth-grade student visitors would stay for four nights at the Camp. Students were led on beach and wood hikes by a crack team of naturalists. In the winter, there were snow shoe hikes and ski trips. Canoe trips on the Crystal River was a staple activity as were “get lost” hikes.

Gus Leinbach bought the camp in 1970 and started the Innisfree Project which was named after a William Butler Yeats poem by that name. Gus was an educator from Ann Arbor who set up the camp with the concept of self-direction for the campers and counselors. If you had an idea, a skill, and interest then you could form your idea, pitch it to a mentor or guide to help, propose it to the rest of the campers and get a group together to do what you wanted. There was a bike shed with tons of parts to work on building bicycles, an old car to learn how to fix engines, a frozen zoo of found animals that were preserved, and an old orchard with apples to pick. The kitchen always seemed to be open for campers to come in and help. It was a true community experience that offered endless possibilities to explore, create, invent, and express.

Gus and his wife Paula operated Crystalaire on Crystal Lake before establishing Innisfree. Camp Lookout “spun off” from Crystalaire and still carries on the tradition of self-directed camp life, where campers and counselors create their own inventive activities. Gus died in 1988, and Innisfree was sold and is still operated as “Camp Kohana.”

During the summers at Innisfree, trips were offered and campers traveled on bikes along the roads of Leelanau and to faraway places such as New England and Isle Royale. I have recently been in touch with Carolyn, my co-leader of a small group of campers to Isle Royale. We both still agree that it was the best trip ever.

In the summer of 1984, we loaded the van with campers and equipment, and we were on our way to meet the ferry boat at Copper Harbor. The trip to the ferry gave us the opportunity to get a sense of the cast of characters within the group. Our first stop was on the Keweenaw Peninsula where I parked the van and made everyone hike up a giant hill to an old fire tower. I insisted that the view was worth it. Everyone was stiff from the long trip across the Upper Peninsula and needed to stretch their legs.

We ate delicious thimble berries along the trail, as I regaled the group with stories of the awesome view from the old fire tower. We got to the top and all we saw was a big block of cement with some metal pieces sticking out. The Forest Service had removed the tower. From that low point, on a high place, it was all downhill to Isle Royale.

The ferry boat at Copper Harbor was surprisingly small. We loaded our backpacks and were off. Lake Superior was very rough that day and many in the group were sick. The water calmed as we approached Isle Royale, and were greeted by a blast of warm air. Camper Emily said: “It smells like pine air freshener!”

We were warned about foxes that would steal food by the Rangers as we unloaded our gear. Willy, a short boy from the Philippines, and Steven, a lanky Inuit, were captivated by the idea of seeing a fox. They rigged up an apparatus for tricking the fox as we set up camp at Rock Harbor.

After being splashed by the water of Lake Superior, it was surprisingly hot at the campground. Emily emerged from her tent and informed Carolyn and I that she had changed her mind about the trip. She demanded a helicopter. She wanted to go home. After some tears and anguish Emily was ready to listen. We explained there would be no helicopter and she was with us for the duration of the trip.

Somehow we had ended up with a large cache of frozen hot dogs. Everyone had eaten their fill so Steve and Willy decided that a hot dog would be perfect fox bait. While foxes stole food we informed Steve that he was not allowed to feed them due to park regulations. Not to be thwarted in his quest to see a fox Steve rigged up hot dog on a bungee cord on a string that he could pull just before the fox grabbed it. He was up all night swatting mosquitos and outfoxing the fox.

The water of Lake Superior is known for being frigid, but late summer sun beats down for long days on the inlets and coves of Isle Royale. The water there becomes delightfully swimmable. Large slabs of granite warmed by the sun made fine places for our group to rest after a plunge. The balance of our trip was spent hiking and swimming in Royale coves and inlets.

One afternoon, when we made it to camp on the early side, we decided to build a sweat lodge out of our tent poles and fly tarps. We were near the end of our week on Isle Royale, so by this time all the campers were pretty good friends and didn’t mind trying something new. We built a fire and found some upland cobbles to heat up. We all got on our bathing suits and crawled into the makeshift lodge. The hot rocks were placed in the center and we all sat and sweated until we couldn’t stand it anymore. With lots of hollering, we all ran through the busy campsite and past the families quietly camping. As a group we all jumped off the dock into the deep Lake Superior water. It was then I knew that we had changed the campers’ lives.

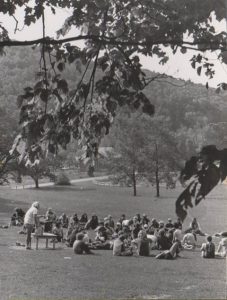

After dropping off all of Steve, Willy, Emily and all the rest, Carolyn and I returned to Innisfree where the late summer band camp was underway. The Big Reds were blasting fight songs out into the Manitou Passage and Big Pig was watching the band maneuvers from his sty near the football field.

The site where the Camp was on Pyramid Point is amazingly beautiful. The high bluff above Lake Michigan was lined with trees to sit in and among and gaze at the sunset. And the beach below with the rustic waterfront was a wonderful place to play. But the real beauty of Innisfree was in the people.

S. A. McFerran is a graduate of the National Outdoor Leadership School and has led six, 24 day wilderness courses in addition to an Antioch College Environmental Field Program. He has led outdoor programs for Northwestern Michigan College, Appalachian School of Experience, Group and Individual Growth and Traverse Area Public Schools. He worked as a naturalist and trip leader at Innisfree.