A sponge is the antithesis of a super hero. It stays in place, sifting out plankton (microscopic algae and animals) from the water that passes through its body. Its body is not of great interest, lacking appendages altogether, not even possessing tentacles that might enwrap evildoers and others that would do it harm. Its personality is not engaging, either, since it does not have a brain.

To get its food, it has many small openings that take in its tiny prey, and a few larger ones that expel the water it has cleansed. The pumping system that carries on the circulation is primitive: cells with tiny whip-like appendages (flagella) line passageways, setting up the current. There are no robust hearts in sponges.

A simple animal reproduces simply. In some species of sponge, balls of cells (gemmules) form in mid- to late summer that can break off from the parent animal and grow into a new sponge somewhere else. This asexual form of reproduction is perhaps the most common means of making new sponges. However, sperms and eggs can be made inside its body, those fertilizing each other in a display that has nothing to do with affection. You wonder, without courtship, without males showing off what they’ve got, what is the point of reproduction like that?

A simple animal reproduces simply. In some species of sponge, balls of cells (gemmules) form in mid- to late summer that can break off from the parent animal and grow into a new sponge somewhere else. This asexual form of reproduction is perhaps the most common means of making new sponges. However, sperms and eggs can be made inside its body, those fertilizing each other in a display that has nothing to do with affection. You wonder, without courtship, without males showing off what they’ve got, what is the point of reproduction like that?

Sponges do have a skeleton of sorts, however. In the ocean, some of them have a soft one made up of spongin, a substance that becomes flexible and absorbent upon being rehydrated. Those sponges have been used for hundreds of years in the Mediterranean Sea and elsewhere for scrubbing everything from floors to human bodies. Mostly replaced by plastic substitutes, they are occasionally used today.

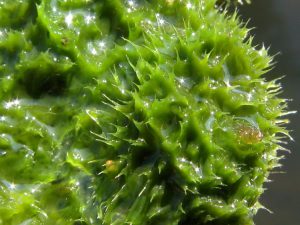

Many years ago I took a course in invertebrates at the University of Michigan’s Biological Station at Pellston, Michigan, and was surprised to learn that we have a freshwater sponge that inhabits our lakes: Spongilla lacustris (a few other species can be found here, too). As I observed it, its body most often was in the form of a greenish blob attached to sticks or pondweed–the green color, I found out, came from algae inhabiting the animal. It was not at all gooey or gelatinous, but felt rough to the touch and a bit like glassy bits stuck together when dried. Unlike its ocean brethren with its spongin, it had a skeleton made of crystal-like tiny elements made of silica, the same stuff that comprises most of our sand in Northern Michigan.

At least one animal appreciates Spongilla–but not for its appearance or life habits. Spongilla fly larvae feed on it with zest, later pupating to become small flies we are certain to ignore among the multitude of other flies that hatch in lakes and ponds. No life form–not even the sponge–is too humble to escape predators.

Spongilla is very particular about where it lives: it must have the cleanest, purest water around. For that reason, it is considered to be an indicator of pristine, unpolluted lakes. Far from being a pestilence, freshwater sponges are a gift. We should not condemn them for what they are not—gifted superheroes of the animal world. They are not delicious, not cute, not pretty, but they do constitute a component of our most treasured biological communities, the clear lakes that grace our landscape in Northern Michigan. Let us rejoice in their presence here.

Thank you for the informative article!

I am a researcher and have been studying sponges in the Great Lakes for the past couple of years. We have evidence of large numbers of sponges which were in the Boardman River in downtown Traverse City in 2015. Would you happen to know if they are still present?

Hello Chase! The author has been notified of your comment, and will be responding directly to you. How exciting, freshwater sponges in the Boardman!