I knew from my friend’s lively cry that something big was afoot: “There is some kind of colonial animal living over here!”

She was knowledgeable about outdoor creatures, so I had little reason to doubt her unlikely comment. I came running over to where she was pointing.

“There, there, at the lip of the spillway—can you see it?” She was pointing at something twelve feet from where I stood on the concrete abutment above the dam that released water from Lake Dubonet to the Platt River system below. “No, I can’t see—it’s too dark!

“Just look. It’s perched on the edge of the spillway.”

My eyes were getting used to the shade cast by the abutment. “I see it!” I proclaimed, “and I think I know what it is,” I replied with a bit of hesitation in my voice. “It’s a freshwater sponge! I haven’t seen one in years. Let me get a picture of it.”

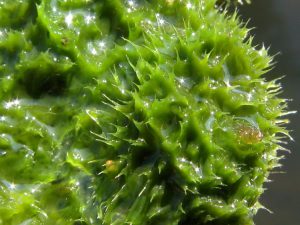

I worked myself down, as close as I could to where the thing was growing. It looked like a mass of gelatin, as large as a loaf of bread, without any recognizable appendages, without a head or a tail. Colonial animals, indeed! What else could it be?

I took a couple of photographs with my camera held down as close as I could get it to the creature. The flash went off, so dark it was down there. I include the view in this article along with one taken by someone else, someone with an easier animal to photograph.

When I got home, I immediately began to have doubts about my identification. Freshwater sponges are not gelatinous, for one thing. They are rough to the touch, and generally green. I thought about my Invertebrate Biology course I had taken so many years ago—and I remembered. I emailed my friend: “It’s not a freshwater sponge. It’s a bryozoan, a moss animal!” Not having seen the species for nearly forty years, it was easy to see how I could have misidentified it.

Bryozoans are sedentary creatures made up of individuals with scores of tentacles, all of them connected to a horseshoe-shaped structure called a lopophore. They are not related to corals—which do not have a lopophore—but extract food from the water the same way they do: filtering out living organisms. This they do by movements of their tentacles and the cilia (moving hairs) upon them.

Like sponges and corals, they encrust various substrates—wood, rock, old tires, even water intakes–scarcely moving during their lives. The species my friend had found, Pectinatella magnifica, is known to move as a young colony, at the rate of two centimeters per day. Its possibilities for adventure are clearly limited by its sluggishness.

“Bryozoan” translates from the Greek as “moss animal.” In both freshwater and salt water, some species form mats somewhat reminiscent of a bank of moss, though they are rarely colored green. The species I photographed, genus Pectinatella, secretes a gelatinous outer body that looks like an unappetizing jam one might put on bread. No one would be tempted to do so, however, given its unprepossessing appearance.

However they might offend our mammalian standards for beauty, bryozoans choose attractive ponds and streams to live in: they prefer unpolluted water, water uncontaminated by mud, debris, or pollutants brought in by humans. Just as lichens point to unpolluted air, bryozoans indicate clean water.

The life cycle of Bryozoans lacks the drama of sperm from one colony actively seeking out eggs in another. Generally, sperm cells from one colony fertilize eggs from the same: a larva grows from the fertilized egg, and is eventually released into the water, often as the colony dies at the end of the summer season.

No one brags about the bryozoan he has captured. No one raves about how good they taste. No one tells of the sport they had in catching their first bryozoan. They live uninteresting lives unaffected by the major currents of a world dominated by other organisms. Does that make them less interesting to those of us who know them? Not at all.