Historians love it when they find a new source of information that sheds light upon a subject they are interested in. So it was when, after idle searching on the internet, I came across Industrial Chicago, Volume 6, Logging Interests, a book that offered plentiful information about Perry Hannah, Albert T. Lay, and the Hannah Lay company, the firm responsible for the building of Traverse City. Reading the book in the comfort of my home, I learned about the company not from the limited perspective of local history sources, but from Chicago-based ones. In addition to information about the company itself, the narrator told anecdotes about founders of the company, Hannah and Lay, stories that had lain untold so far in the telling of our history.

Some information simply confirmed what we thought we knew. Did the lumber taken from Northern Michigan help rebuild Chicago after the great fire of 1871, the fire allegedly started by Mrs. O’Leary’s cow? Indeed it did. We are told that the Hannah and Lay yard lay south of the fire’s devastation. The company was well positioned to supply lumber for the rebuilding process.

Exactly how profitable was Hannah Lay? The reader of Industrial Chicago is given figures about board feet of lumber produced at mills of the Hannah Lay empire, but these are difficult to interpret. How much is a billion board-feet after all? A better indicator is this: In 1895, the year of publication of the book, the company owned the Chamber of Commerce building at the corner of LaSalle and Washington outright. It was valued at the time at three million dollars, a sum in today’s money that would total closer to 35 million. A postcard from the time shows its magnificence: fourteen floors with astounding ornaments—a palace, which has been replaced, sadly, by the Chicago Board of Trade building.

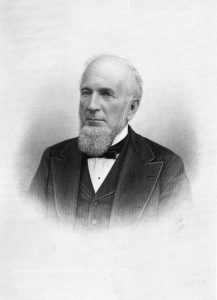

What does Industrial Chicago tell us about the founders of the company? About Perry Hannah, it revealed not much that we didn’t know. I found it interesting that he obtained a Common School education probably consisting of ‘reading, ‘writing, and ‘rithmetic, before he moved to the Port Huron area with his father at the age of 13. There he learned the art of rafting logs to be sent down the St. Claire river to sawmills to be sawn into lumber. His roots were close to the working class, unlike his partner Albert T. Lay.

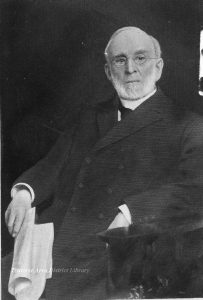

Lay was educated in private schools until the age of 16, presumably a more rigorous education than the public schools at the time. His father was a legislator to the US House of Representatives for the state of New York. Is this why young Lay’s signature appears bold and competent, in contrast to Hannah’s—that reading and writing were activities he had spent much time doing? At first, he stayed in Traverse City to set the new mill near the mouth of the Boardman River to working properly, but five years after arriving at the rude settlement carved out there, he and Hannah resolved to change places. Perry Hannah would stay in Traverse City and Lay would handle the Chicago operations. Lay, perhaps because of his superior education, would be involved in the more intricate dealings with suppliers and major customers.

Albert T. Lay’s early years in Traverse City have not been described by previous historians. We know that in 1853 he ran against James Strang, the Mormon leader at Beaver Island, and lost that election to the Michigan legislature. He oversaw the construction of a steam-powered sawmill at edge of Grand Traverse Bay. He probably approved the building of the first Hannah Lay store, just 16 x 20 feet, the ledgers of which still remain at the Bentley Historical Library in Ann Arbor.

Lay named Traverse City. In 1853, seeking a postal route for the settlement, he presented the name “Grand Traverse” before officials in Washington, D.C., later accepting their suggestion to strike out the “Grand.” It would be Traverse City, the “City” element added later.

What does one do to found a city? In the past, Harry Boardman and his son Horace were given credit for founding Traverse City. They bought land here, built a sawmill in 1847, and began the production of lumber at that early date. A hundred years later, in 1947, historians convinced city leaders that the centennial celebration should occur in that year. The settlement began with Boardman’s acquisition of land and the subsequent logging of the trees on the property—no matter that the Boardmans never put down roots here. They bought the land and sold it soon after.

The whole question of who founded the City–and when–seems silly to Native Americans who had set up camps here from prehistoric times. Still, there is something in a name. Whoever names a place deserves credit for that act. By that rule, Albert T. Lay founded the City.

One story about the rude, uncivilized nature of the Traverse area tells about Lay and a judge friend from Manistee who had come north to visit the logging operation at the foot of Grand Traverse Bay. The judge promptly identified a man in the sawmill crew as a run-away criminal wanted for the murder of his own daughter. Quickly, he made Lay the deputy sheriff of the new region, and then named him deputy county clerk, deputy county treasurer, and deputy school inspector. In short, Albert T. Lay temporarily held all the offices for the soon-to-be Grand Traverse county. After the sawmill was stopped to secure men for a jury, the trial proceeded apace, the defendant declared guilty. He was tied to a post at the mill (since there was no jail), and was sent downstate to serve a life sentence in prison there. Justice was done with the aid of the young owner of the sawmill at the mouth of the Boardman.

In praising Lay, I do not want to disparage Perry Hannah’s contribution to Traverse City. After all, he did stay at this ramshackle outpost for 47 years, keeping away from the enticements of a grand city—Chicago—only a day away by railroad or steamer. He pushed to have the Northern Michigan Asylum located in Traverse City and personally guaranteed support to the Carnegie library, thereby assuring it would be built on Sixth Street, opposite his home. He donated land to churches and generally treated people fairly and with generosity. When Traverse City was a small settlement, he—and his company—ruled the town, but for all that, he was a benevolent despot. We could have done much worse.

At the same time, we should not neglect the other founder of Traverse City, Albert T. Lay. A small park on Union Street bears his name, but few persons remember what he did for the community. There is no statue, as there is of Perry Hannah across Union street, though a plaque is mounted on a boulder that reads: Lay Park: To commemorate Albert Tracy Lay, pioneer lumberman, who, with Perry Hannah, in 1851 founded the first permanent settlement on the site of Traverse City.” What elegant simplicity! The two together founded the city.

By this account, it seems to me that it was The Postmaster’s office who should get credit for naming Traverse City? They rejected the name Lay gave them and pretty much said it will be Traverse City.

I was leaning towards honoring T. Albert Lay for the naming of Traverse City. I believe he went all the way to Washington, D.C. to get the postal route named. He wanted “Grand Traverse,” but the official said “Traverse” would be better. Now I wonder when “City” was attached. Was it immediate? In the first issue of the Grand Traverse Herald (November, 1858) “Traverse City” is clearly printed. Perry Hannah is, indeed, a great man, but I was hoping Lay could gather a small measure of fame.