by S.A. McFerran, B.A. Environmental Studies, Antioch University

A cognoscenti of fishers met at “The Shack” that was located on the Boardman River near the community of Keystone. Operated by Traverse City Fly Club founder and barber, Art Winnie, and frequented by nine of his friends, The Shack was a fishing camp that encourage anglers to fish stretches of the Boardman River, South of Boardman Lake. There was much to discuss at The Shack meetings because the grayling were disappearing and the banks of the river were in tatters due to logging and dams.

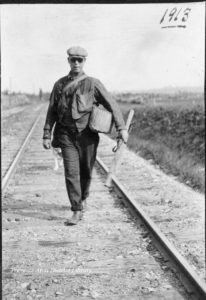

A diary of activities at The Shack was kept. The first entry was March 3, 1913. Visitors such as conservationist Harold Oswald Titus and Remington Kellogg of the United States Biological Survey joined members for fishing trips on the Boardman River. Also noted in the Shack Diary was the planting of fish in the Boardman River and its tributaries. (1)

The milk cans that were dropped off at the Keystone train station each contained 2000 trout. The water in the cans had to be changed hourly until the fish were released into the Boardman and its tributaries. Creeks flowing into the Boardman River such as Beitner, Thorpe, Bonath, Jaxon, Sleight and Hogsback all received trout raised in the state fish hatchery.

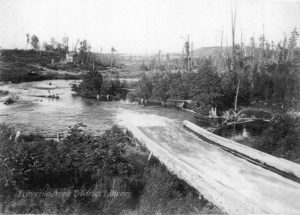

With the forest gone, erosion washed sand into the Boardman and the sun warmed the water. Dams also warmed the water and blocked the movement of fish up and down the river. The elegant structure of the Grand Traverse ecosystem was reduced to a shack, and the grayling died. Self-appointed architects of the ecosystem at The Shack did the one thing they could think of: add fish to the water so that they could catch fish.

The Shack Diary entry dated April 3 – 4, 1920: “Planting Liberty Brown trout as follows: Thorpe Creek,10,000. Shack below the bridge, 10,000. Shack Creek above the bridge, 10,000. From Umlor down in Hogsback Creek, 4,000. Boardman River, 20,000. Between Summit City and Keystone there were planted 294,000 trout of which 112,000 were brook and 182,000 were Liberty Brown.” (The name “German Brown” was changed to “Liberty Brown” in response to anti-German sentiment related to World War I.)

The Shack members had a shortsighted view: If the fishing was good, all was well. The State of Michigan provided the fish to support the efforts of these sportsmen, but not to create an environment in which these fish would naturally thrive. In retrospect the answer is: river restoration. The answer still is river restoration that takes an ecosystem view and includes fish stocking as one measure of the restoration. If the river ecosystem is functioning and habitat cared for the fishing will be good.

River restoration seeks to link ecosystems. The Grand Traverse Bay once teemed with fish and some moved from the Boardman to the open water. Coregonids, a very important and numerous mid-tropic level fish that were preyed on by the trout spawned in the open water of the Bay. The Shack cognoscenti were well aware that the elegant structure of the ecosystem had been lost. Art Winnie: “But here’s where we always put the conservationists…let the perch spawn . . . once every two or three years. Let them spawn and get a new breed in. Then they’d be comin’ pretty good. Look how they used to come up the river.” (2)

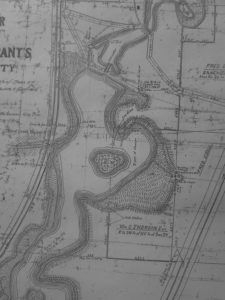

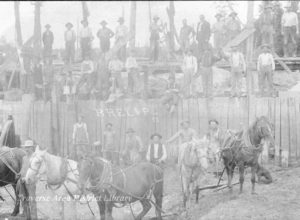

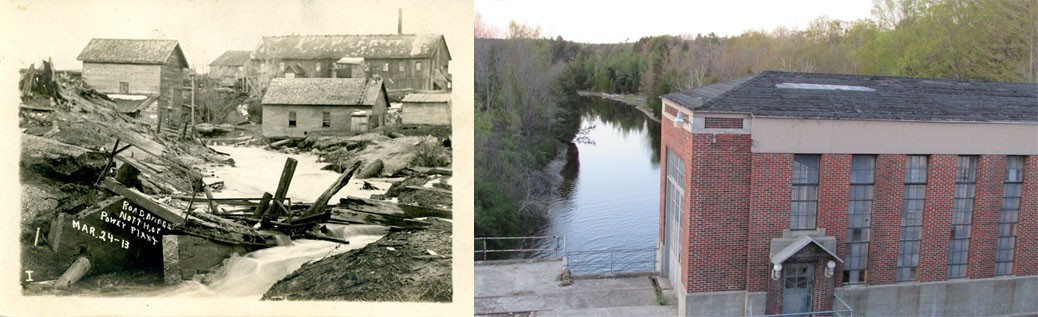

Captain Boardman built his dam in 1847, and the electric power Boardman Dam was built in 1894. The Sabin dam was built in 1907. The Keystone dam was built in 1909. In 1921 the Brown Bridge dam was built. The Boardman dam was rebuilt in 1931. Each of these actions were major disruptions to the ecology of the Boardman River. Dams were also built on the upper reaches of the Boardman River in Kalkaska, South Boardman and Mayfield’s Swainston Creek. (3)

There was disruption of the river ecosystem and disruption of the large Grand Traverse Bay that once teamed with whitefish, herring and cisco. The bay was host to “pound nets” that devastated corigonids. The State of Michigan managed the river and open water separately. Progress is now being made in raising coregonids in the state hatcheries. There will be another attempt to re-introduce grayling.

With the removal of the Boardman Dam and the Sabin Dam the only barrier that will remain to upper stretches of the Boardman is the Union Street Dam. The restoration of the Boardman River could mean the restoration of fish populations in the Grand Traverse Bay.

A cognoscenti of fishers will meet January 18, 2018 to consider the passing of fish from the Bay to the River and River to Bay. Restoration of the elegant structure that once rested on both streams where small fish were hatched and the big bay where fish grew big will be considered. Architects of the ecosystem now have access to resources that Art Winnie and the boys who built The Shack could only dream of.

But will an elegant structure that resembles the ecosystem that once stood be able to be built? I think not.

For more information on the FishPass Project, visit the Great Lakes Fishery Commission website. The next meeting of the Boardman River Implementation Team will take place on January 18th, from 1:30-3:30 p.m. at the Traverse City Governmental Center, Commission Chambers, 400 Boardman Avenue, Traverse City, MI. Meetings are open to the public.

Stewart. A. McFerran teaches a class on the Natural History of Michigan Rivers at NMC and is a frequent contributor to the Grand Traverse Journal. Many of his contributions, including this piece, are written as a direct result of interviewing people with stories to tell.

References

(1) Grand Traverse County Historical Society. Currents of the Boardman.

(2) Art Winnie interview

(3) https://gtjournal.tadl.org/2017/jack-robbins-and-the-tortured-landscape-of-the-boardman-river-valley/