by S.A. McFerran, B.A. Environmental Studies, Antioch University

The new theology has borrowed, without credit, one of the fundamental planks in the old religion: despite his disclaimers, man stands at the center of the universe. It was made for him to use, and the best and wisest men are those who use it most lavishly. They destroy pine forests, dig copper from beneath the cold northern lakes, and run the open pits across the iron ranges, impoverishing themselves at the same time they are enriching themselves: creating wealth, in short by the act of destroying it, is one of the most baffling mysteries of the new gospel. ~Bruce Catton (1)

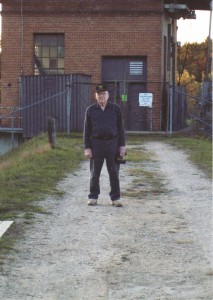

From the front window of his farmhouse Jack Robbins has borne witness to the lavish use of the Boardman River. The Robbins farm is in the Boardman Valley on Cass road near the site of the Boardman dam.

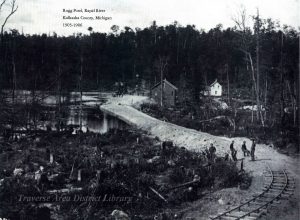

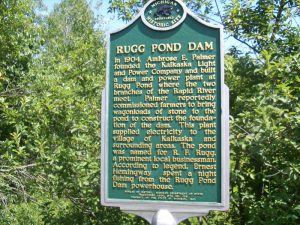

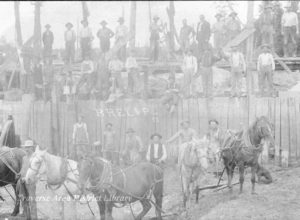

Captain Harry Boardman first dammed the river for his mill before the turn of the last century, around 1847. Many subsequent dams have either washed out or been removed. The most recent dam removal is almost complete and is restoring the river to its natural state. The river restoration effort was aided by a historic map that Mr. Robbins had tucked away in his farmhouse.

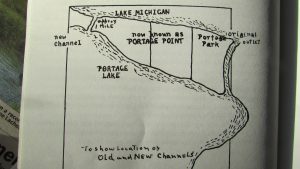

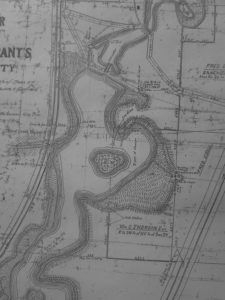

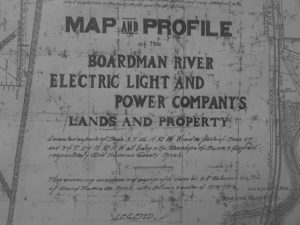

The map took two years to make (1915-1916) and was drawn on a special fabric by surveyor E.P. Waterman. The detail on the large map includes the location and elevation of bench marks that assisted in the removal of the original dam built in 1894. The Sabin dam is also included on the map.

Over one hundred years later Mr. Robbins shared the map with the Army Corps of Engineers Manager Alec Higgins (2). The map was used to locate the historic channel of the Boardman River while the 1931 dam was removed this year.

Jack Robbins bought his farm in 1951 and fished the deep holes above the Boardman dam until October 1961 when the Keystone dam washed out and filled in the holes with sediment. He showed me the location of the original Boardman River Electric Light and Power dam from his front window. His map reveals the points of interest such as the grade of a carriage road that lead to a wooden bridge just across from his farm.

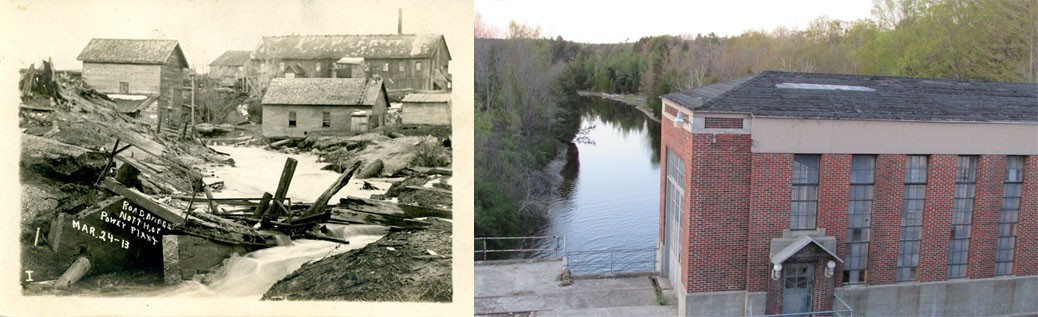

In November 1894 Boardman River Electric Light and Power completed construction of its first dam and turned on the electricity. This original dam was just downstream and twenty feet lower than the Boardman dam that was just removed. The powerhouse was right across the road from the Robbins farm.

More power was needed and so the Sabin dam was built in 1907. The Keystone dam was built in 1909. In 1921 the Brown Bridge dam was built. The Boardman dam was rebuilt in 1931. Each of these actions represent major disruptions to the ecology of the Boardman River. Dams were also built on the upper reaches of the Boardman river in Kalkaska, South Boardman and Mayfield’s Swainston Creek. (3)

The dam on Swainston Creek washed out in 1961. That large slug of floodwater washed out the Keystone dam during a rainstorm. Jack Robbins remembers this event well and has stories to tell about how the dam operators attempted to avoid disaster.

9.5 million dollars was spent in 1979 to renovate the dams on the Boardman River. It will cost $2,834,535.60 to remove the Boardman and Sabin dams, return the river to its original channel and restore the banks. (4)

River restoration is an art and a science. River restoration is taking place in watersheds across the country and represents a change in the “new gospel”. It would be approved by Bruce Catton. Mr. Robbins is well aware of the environmental destruction that has taken place in the Boardman Valley which began in the logging era, and he approves of the Boardman River restoration project.

Stewart. A. McFerran teaches a class on the Natural History of Michigan Rivers at NMC and is a frequent contributor to the Grand Traverse Journal. Many of his contributions, including this piece, are written as a direct result of interviewing people with stories to tell.

References:

- Catton, Bruce. Waiting for the Morning Train: An American Boyhood.

- Higgins, Alec. Email interview with the author.

- Grand Traverse County Historical Society. Currents of the Boardman.

- FINAL CONCEPT DESIGN REPORT, Boardman and Sabin Dam Removals, BOARDMAN RIVER DAMS IMPLEMENTATION TEAM December 2014; 301 S. Livingston St., Suite 200, Madison, WI 53703 | 608-441-0342 | interfluve.com; 10850 Traverse Highway, Suite 3365, Traverse City MI 49684 | 231-922-4290 | urs.com