Entries in the Grand Traverse Normal School record book fill dozens of pages in five bound volumes, beginning in 1913 and ending in 1952. Written in the elegant cursive hand of an educated person, they contain information about young women who wished to become teachers, carefully detailing their grades on the teacher exams, notes about age, educational background, personality, performance in student teaching, along with miscellaneous notes predicting future success as a teacher. Three of them dated 1913-14 are given below:

Rose Fifarek: Age 19; Traverse City High School graduate; No teaching experience. Personality: Not good. Inclined to careless in dressing hair.

Remarks: Work very ordinary. Teaching fair. Doesn’t get into the depth of things.

Ruby J. Shilson: Age 23. Traverse City High School graduate; 3 mo’s teaching experience. Personality: Very good. Remarks: Bright and clever. Did excellent practice teaching. Disposition may cause a failure in discipline.

Laura Bannon: Age 19. Traverse City High School graduate. Personality: Very good. Remarks: Did excellent practice teaching. Original. Fond of argument. Excels in drawing. A very poor speller.

Each of the evaluations were signed by Blanche Peebles, principal of the County Normal School.

A list of grades ranging from fair to excellent were entered for each young woman’s name over 23 areas with which she should become familiar. The diversity of knowledge required for teachers was breathtaking. They should know the rudiments of Agriculture, Civics, the Classics, Grammar, History, Reading, and School law. They should be able to draw, sing or play an instrument, write with good penmanship, and spell accurately. Arithmetic, geography, and physiology should not stump them, nor should manual training . Good grades were not handed out cavalierly—many “Fairs” expressed weaker knowledge and capabilities.

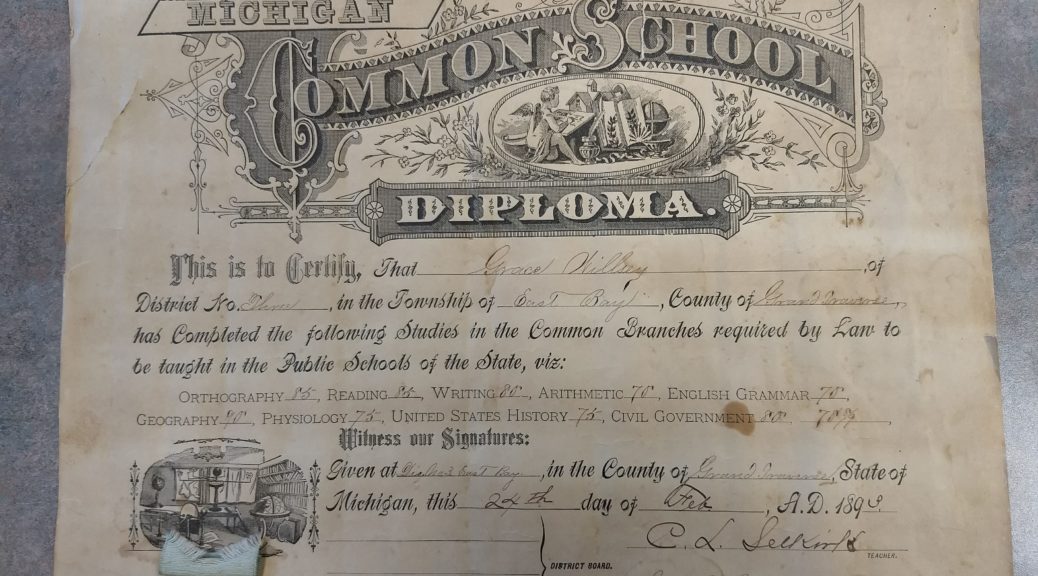

Most—but not all applicants for teaching credentials—possessed a high school diploma. A few had an education through tenth grade, their age as young as 17. For most, the goal was to teach in a one-room schoolhouse, grades one through eight. The teaching certificate most would get would be good for one year—at least for those that had no successful teaching experience. With experience, certificates could be extended for three years or more.

High school teachers tended to be better educated than elementary teachers. Three profiles of teachers are presented here, the descriptions derived from the 1912 yearbook, The Pines:

Miss Emma Shafer: Ph. M. (Masters degree). Teacher of English Literature and German has een with us for two and a half years. She graduated from Hillsdale College and later from the University of Chicago. The senior class feels fortunate in having a woman of Miss Shafer’s character for an instructor in English literature.

Miss Amy Scott, teacher of English and Geometry, came to our high school in the fall of 1909. She graduated from Bay City high school after which she went to the University of Michigan, receiving a Bachelor of Arts. She is a competent instructor and her untiring interest in our welfare has been a great benefit for the high school.

Mr. P. S. Brundage, B. Pd., came last fall to take the place of Mr. Hornbeck and has proven himself to be an able instructor. He has charge of the physics and chemistry departments. Received a life certificate and the degree of B. Pd from the Ypsilanti State Normal School. Also attended the University of Michigan.

Most members of the Central High School faculty had a four-year degree from recognized colleges and universities. Some graduated from smaller colleges such as Olivet and Hillsdale, while other obtained their degrees from larger institutions such as the University of Michigan or the Michigan Agricultural College (Michigan State). At the least, they would have attended the state Normal College in Ypsilanti, now called Eastern Michigan University. The reason for the higher academic achievement of secondary teachers has to do with University of Michigan accreditation. If pupils graduated from an accredited institution with a “C” average, they were admitted to the University of Michigan without examination. To keep standards high, the University insisted that high school teachers in academic areas had to have at least a Bachelor’s degree.

It is notable how young teachers were, both at elementary and secondary levels. All at the elementary level are women, but at the secondary level men are represented, though not in the same number of women. Men or women, few taught longer than a few years at any location. Between the years 1916 and 1921, yearbooks indicate only two teachers carried over from one faculty list to the other. The twenty-year tenure of the janitor at this time stands in stark contrast to the one-, two- or five-year commitments of teachers.

There are plentiful reasons explaining the tendency of teachers to leave their jobs. Upon marriage or pregnancy, women teachers were obligated to resign. In an age before teacher’s unions and tenure, many teachers were not rehired for reasons as trivial as disagreement with the superintendent of schools or the principal. Salaries in Traverse City were not only below those of those with equivalent degrees in business, but fell below average teacher salaries in many local communities. Finally, teachers with several years of successful teaching experience often became administrators, that job paying more than teaching.

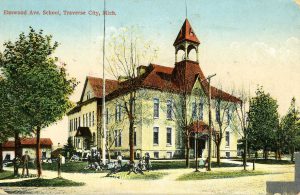

What was it like to be a teacher more than a hundred years ago in Traverse City? The job was not an easy one. In 1894-95 the school year was roughly comparable to the present one. At that time, three terms of different lengths made up the school year, the fall term beginning on September 3rd, the winter term beginning on January 7 and lasting until March 29, and the spring term beginning on April 8th, ending on May 31. As with today’s schedule, a two-week Christmas vacation and a one-week spring break is granted to pupils and teachers. In 1895, school hours were also similar to today’s; school opened in the morning at 9 o’clock and ended at 3:30. One and one-half hours separated the morning from the afternoon session.

Class was conducted in a manner somewhat different from school nowadays. Typically, students were asked to stand and recite—give answers to questions asked by teachers. In the Public School Handbook for Traverse City, teachers were advised to call on students “promiscuously” and never to repeat the question, these techniques designed to compel attention in classes. Some advice given there holds up today:

Be independent of the textbook as far as possible.

Be animated and enthusiastic, but do not be noisy and fussy.

Never address your students in a petulant, ill-natured manner…

Avoid loudness and harshness of tone, and cultivate purity of voice and sweetness of expression.

Kindness and affection are the strongest elements of a teachers power, when set in an iron frame.

If a pupil persistently disregards the regulations of the school…, send a warning notice to the parents before resorting to harsher measures.

In general, the use of corporal punishment was rare, though it was permitted by school regulations at earlier times. At present, it is forbidden in the state of Michigan.

The curriculum teachers taught varied considerably from that taught now. Kindergarten was firmly in place before the beginning of the twentieth century, but there was no effort to begin children on the path to reading—as there is now. Kindergarten was a time to prepare children—socially, emotionally, physically—for the academic world to come.

In general, curriculum objectives were vaguely defined, existing mostly as segments of textbooks that were to be covered in each grade. In first grade, for example, children were to learn 75-100 common words—not just to recognize them, but to understand their meanings. From the beginning, phonics were not neglected, nor was writing in cursive, that the preferred style of writing to be used by first-grade teachers. The curriculum of subjects like arithmetic, geography, science, and history was laid out in the form of sections of appropriate textbooks to be completed at the different grade levels. In contrast to today’s detailed lists of learning objectives, there was no explicit statement about what skills or knowledge should be learned at any level. Apparently, objectives must have been fairly well standardized among different textbooks, since the series of books used changed quite regularly. It would have been impractical to have teachers learn a new scope-and-sequence with every textbook change.

Class sizes can be determined by looking at photographs of classes at the elementary level and at class yearbooks at the Senior High level. A cursory examination of ten of them reveals a range between 14 and 36, the most common number centering around 27 or 28. Thus, the numbers are not far different from today’s, though they amount of organization required at the elementary level must be even greater than demanded of teachers nowadays. It is hard to conceive how to organize a classroom with students ranging from first-grade to seventh and eighth grades. Small groups of children about the same age must have tackled assignments together while the teacher moved from group to group. No doubt, older students worked with younger ones, too.

In high school classes varied in size. A note in the Evening Record in 1908 informed readers that a school evaluator from the University of Michigan observed that classes were too big in Traverse City with some approaching 45, when the best class size was said to be 25-30. In agreement with this note, a report to the Board of Education in 1906 displays a comparison of Traverse City to other school districts in Michigan with regard to class size at the secondary level. With an average of 36, the local district was the worst in this regard, that figure some six pupils higher than the next-highest school on the list

The same report indicated how many periods for each high school as well as the number of classes teachers were expected to teach. Traverse City had six periods at the time, and teachers were expected to teach all six of them, that schedule permitting no preparation period. It was the only school of the 17 compared that made such heavy demands on its teachers.

Teacher salaries varied within the district for several reasons. First, women teachers were paid less even if they had the same credentials and experience. This was a common practice at the time, the rationale perhaps relating to traditional views of the man as the breadwinner for a household. Second, secondary teachers were paid more than their primary colleagues. In 1908 primary school teachers were paid salaries of approximately 500 dollars per year at a time when an average worker made about 600 dollars. Secondary teachers earned somewhat more, some approaching 900 dollars. The reason for the discrepancy was that secondary teachers had a Bachelor’s degree, while primary teachers often had Normal School training of a year or two after high school graduation. A B.A. carried salary advantages.

A third reason salaries differed among the teaching staff was that the school superintendent would meet separately with each teacher in May and present an offer to her/him individually. Through this practice, teachers could be offered more or less money for a variety of reasons: a pleasing personality, an attractive appearance, connections with persons the superintendent knows, experience teaching at various institutions, an educational background at a more prestigious university. At the turn of the twentieth century, there was no collective bargaining and no tenure.

Teacher salaries were lower in Traverse City than in other districts in Michigan. Evidence from the proceedings of the Traverse City school board points to teacher resignations attributed to better offers from other districts in and out of northern Michigan. In 1917 local teachers submitted a petition to the mayor of the city, asking for a salary increase in the face of the increased cost of living: it is unclear if they were successful. The Traverse City Press in the same year conducted a discussion about teacher salaries, the consensus being that teachers deserved more, but the community was unable to pay (this was a time of economic depression in the Traverse area). From that day until the present, teacher salaries in Traverse City have lagged behind those of other equivalent cities in Michigan.

In early Traverse City schools, the work was difficult, the rewards few. Teachers rarely made a career out of teaching for economic reasons, for reasons relating to the difficulty of the work, and for reasons connected to social values that required women to resign after marriage. Standards were quite low—especially for elementary teachers who often had little more than a high school education. Still, in the face of these and other obstacles, the business of education got done. We should remember the dedication and sacrifice of our early teachers.