Anyone living in Northwest Lower Michigan within a region extending from Leelanau through Kalkaska counties, will not forget the big storm of August 2, 2015. It was one of those signature events that cause you to remember exactly where you were when it happened. I was on the phone with a friend: we talked nervously, wondering when the connection would go dead, all the while thinking we should both head for our separate closets in case the roofs of our homes should blow away. Trees bent the way you see them do in videos of hurricanes and trash containers became missiles driven by the wind. In fact, on the basis of observed damage, the wind speed did exceed that of a category 2 hurricane in places, more than 100 miles per hour.

What do storms like that do to forests? Are there winners and losers in such a catastrophe? What effects can be observed after one, fifty, and a hundred years later? These are the questions that intrigued me as I walked through a devastated forest in Leelanau county, a few weeks after the Big Blow. Mostly, the trees tipped, though a few were broken off at the middle. Earthen mounds containing tree roots made walking difficult as you took circuitous routes to get to places that used to be reached directly. The uneven ground of mature forests is due to tipped trees, some brought down a century or more ago. That is one long-term consequence of the storm: the hills and valleys of the new forest could remain for centuries.

A hardwoods in Michigan is generally covered with last year’s un-decomposed leaves from last two or three years. Called leaf litter, it acts as a blanket, keeping moisture in and repelling the growth of small wildflowers, ferns, and other small plants. When the leaf litter is torn apart as it is when a tree tips over, opportunities abound for seeds waiting for their chance. They sprout and grow rapidly, their growth speeded by sunlight that touches the forest floor as tree canopies no longer provide shade. Along with natives, invasive plants like garlic mustard thrive in the disturbed ground. It is a changed habitat for all and those best adapted take advantage of their genetic heritage.

Certain trees win out in the competition for sunlight, casting others in shade as they overtop them. Shade intolerant trees grow the fastest—birch, black cherry, poplar red pine—while shade tolerant trees like sugar maple, American beech, and white pine bide their time in their shade. Before long, only the seedlings of those trees will dominate the forest floor, since only they can tolerate summers’ complete shade. Poplars and black cherry (together with scattered oaks and maples) will dominate the first generation of trees on the hilly moraines of Leelanau and Grand Traverse counties. In time, they will be replaced by hemlock, beech, and a more dense population of sugar and red maples.

Naturally, a few middle-sized trees will survive a massive blow-down after a storm. After wind storm, with sunlight flooding in as the dense overhead canopy disappears, they respond to the changed conditions for growth. Buds under the bark spring to life, sending out small, leafy branches. Called epicormic sprouting, this phenomenon has serious consequences for those wishing perfect timber for logging, since the wood grain is interrupted by new vascular tissue that supplies the new branch. Look for epicormic sprouting in forests damaged by the August 2nd storm.

Secondary effects of a severe windstorm are too numerous to count. The loss of nests and dens that occupied old trees, the loss of stable food sources like acorns and beechnuts, the disappearance of animals that prefer the cool, deep shade of a mature forest (like land snails), and the opening of hilly terrain to erosion are four obvious ones, but even those only scratch the surface. Of course, the winners will move in—the deer that browse on shoots of poplar, ground squirrels, rabbits, blackberries and raspberries, and uncountable weed species—as the older residents die or move out. It is a scene that has been re-enacted for untold thousands of years.

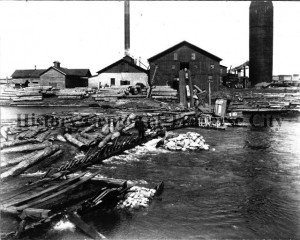

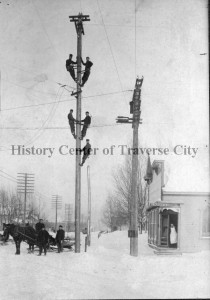

Whenever something catastrophic happens in nature, we know it is wrong to take sides—since some living things require the housecleaning that enables them to thrive. At the same time, we cannot help but grieve for what has been lost. After all, isn’t a mature hardwoods rarer and more precious than acreage covered by poplar sprouts? Virgin timber is very hard to find in Northern Michigan: Ever since the nineteenth century loggers have destroyed those ecosystems without mercy. So it is that we feel a pang in our hearts when the big trees go down and the sunlight pours in. We know we have lost something that took centuries to form. The Big Blow damaged far more than human property. It destroyed a natural relic that is not easily replaced.