From an original interview by Brenda Kay Wolfgram Moore in Kingsley, Michigan, undated. Webster added memories in an interview with Peter Newell, November 12, 2014.

This month’s “Celebrate the People” honors Floyd Webster, historian of the village of Kingsley since 1952, whose countless hours of work in that volunteer role has developed in to the local history collections held at the Kingsley Branch Library. Webster’s reminiscences focus on his years of service in World War II. Few of those who served remain to tell their stories; 2015 marks the 70th anniversary of the end of that conflict.

While Grand Traverse Journal typically features stories concerning our local region, we recognize the importance of recording and publishing the stories of our residents, both for future generations and for the catharsis it gives those who have served.

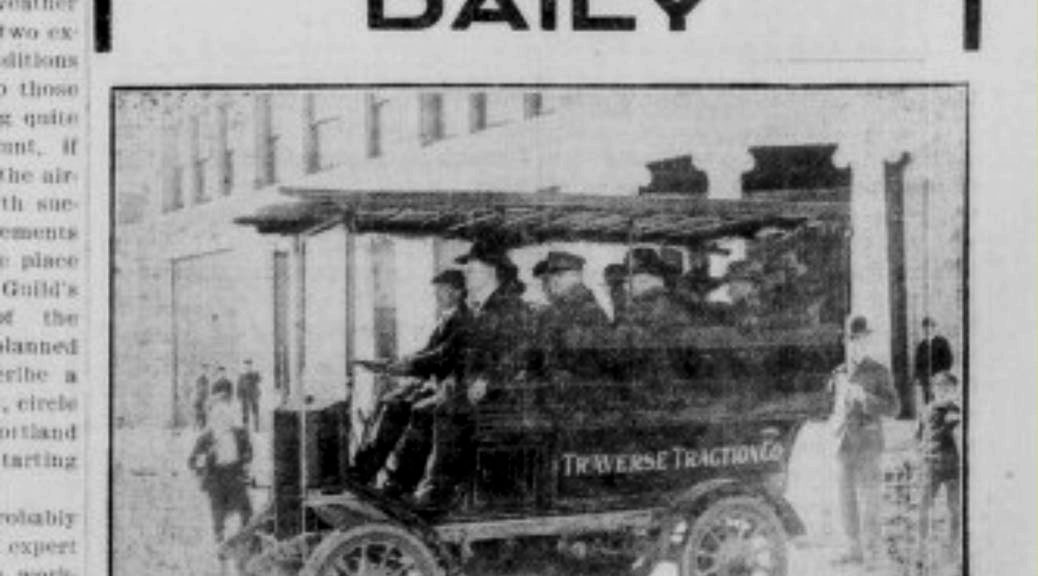

In August 1942, I enlisted in the Army in Traverse City, Michigan. Before my next birthday, unimaginable life changing events happened. Not only would I get married and travel with the Army throughout the eastern United States, but also see terrible devastation throughout most of northwestern Europe. A few days later, I went to Fort Custer in Battle Creek, and soon boarded a train to Chicago. I had rarely ventured far from Kingsley, Michigan and now I was receiving Army training in Chicago, Illinois, where, one day, I happened to be eating at a Wimpie’s restaurant. At a table by myself and being only one of several customers dressed in uniform, I was conspicuous. Finally, a young man, about my age, introduced himself and we began to talk. Gerald Putnam and I formed a friendship and later he introduced me to his sister, Melvina Putnam, whom I would soon be courting.

After Chicago, I continued by train to Little Rock, Arkansas for further training. I weighed 117 pounds, my back pack 109 pounds, so if I had to shoot a bazooka, it would knock me on my butt. Appearing too lightweight for the infantry, I began my training in the renamed Chemical Corps that was attached to the Army Air Corps. Because “Chemical Warfare Service” seemed a bit too harsh after the WWI experience, it was renamed Chemical Corps.

I was being trained to decontaminate troops after being exposed to poisonous gases like cyanide and mustard. The enemy could drop or spray it anywhere to quietly settle over the troops so it was on them before they even noticed it was there. If it soaked into their clothes they might as well forget it. Any kind of gas, mustard, hydrogen, cyanide—there were lots of choices, that could be used for different situations. Though my mask was easy to use, it was bulky and tiresome to always carry over my shoulder.

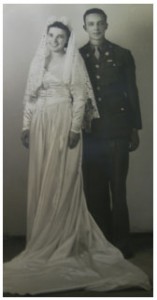

Later that year, I left Little Rock heading for the Putnam home in Chicago to be with Melvina before my transfer to Duncan Field in San Antonio, Texas. After corresponding with me a few months Melvina completed her beautician training and came to San Antonio looking for a position in a beauty shop so we could be closer together. Melvina and I were married February 19, 1943 close to Fort Alamo Riverside Baptist Church. A few weeks after our wedding, Melvina went home to Chicago to live with her sister Pearl.

At the same time, a train transported me and my company to Hampton Roads, Virginia, which was a main hub during both world wars for movement of millions of troops over seas. From there, our ship joined the main convoy off Newfoundland and left for Europe. Over twenty thousand men on nine Liberty Ships left at night. For the next twelve days all we saw was water. I was never a sailor and was really sick at the rail. Still, after days on board the ship, I could not stay below without throwing up. One of the officers noticed and took me above deck to the gunner’s nest and told me to sit in the swivel chair and watch for anything strange in the water. When we reached Gibraltar, we waited for the rest of the convoy to catch up. Our huge convoy entered the most dangerous waters off the coast of Europe. One night, while on watch duty between Gibraltar and England, I saw one of our tankers blown to pieces by a torpedo that must have been launched by a German submarine.

When we reached the English Channel, it was mined and only the British knew the safe passage to the harbor and in order to not be blown up, all the ships in the convoy waited to be piloted through the mine field. While in England, I and my company were assigned to live in the South Hampton area of Stanstead, Essex, England, where we received more training in chemicals like lewisite and hydrogen sulfide. We, in turn, would be teaching it to other allied companies.

My training in detection was mainly defensive and never included how to offensively use poison gas, but I had to know how it was dispersed. The first part of detection training was simple: learn how to crawl through a field strung with wire to the suspected poisoned area, crawl underneath it for 30 or 40 feet on hands and knees, mostly on hands, and prepare to holler, “All is clear.” And hope like hell I was right. If I was wrong, I would probably die as soon as I loosened my mask. Of course, training was a little more complicated than that, because I would have had testing equipment and been with a squad of men to analyze the air content before giving the “All is clear.” After each exercise that was really a test of endurance, I would go back to camp, take a bath, and sit around with 50 or 60 troops joking and laughing, where many off color taunts were tossed about. The ancient taunt, “Do you know what your wife is doing back home?” still caused trouble in 1944. I heard it many times and it was sure to cause a fight between young men who missed their wives and family. Usually their friends would break it up before any great harm was done.

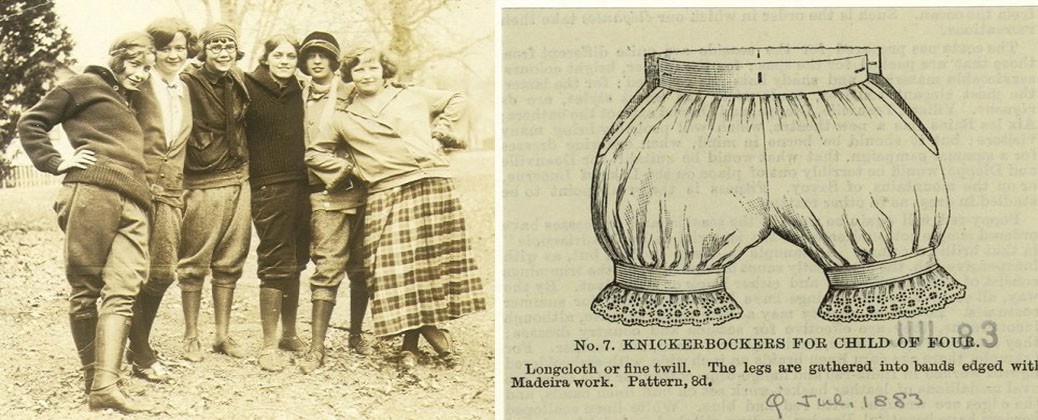

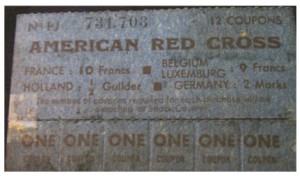

My American Red Cross coupon, good for chow anywhere in Belgium, Luxembourg, France, or Germany was one of the most important documents in my possession and gave credence to “The army travels on its stomach.” Used mostly for meals while traveling, it could even be used to figure exchange rates between those countries. My buddies and I often went on trips near London for lunch, where I, more than once, joined the Brits in bomb shelters during German air raids. On a trip outside London, I saw a girl dressed in army clothing. This was strange to me as I had not seen a girl dressed like that before. I asked her what her uniform meant and she said that she was part of the British Land Army. She and other women did the farm work while the men were at the front. We visited Piccadilly Square, and once even went to Buckingham Palace and stood at the front gate where we saw Princess Margaret when she was about seven years old. She waved at us from one of the upper windows, and we all waved back back just before Princess Elizabeth appeared and took Margaret away from the window. It is nice to remember that moment.

My American Red Cross coupon, good for chow anywhere in Belgium, Luxembourg, France, or Germany was one of the most important documents in my possession and gave credence to “The army travels on its stomach.” Used mostly for meals while traveling, it could even be used to figure exchange rates between those countries. My buddies and I often went on trips near London for lunch, where I, more than once, joined the Brits in bomb shelters during German air raids. On a trip outside London, I saw a girl dressed in army clothing. This was strange to me as I had not seen a girl dressed like that before. I asked her what her uniform meant and she said that she was part of the British Land Army. She and other women did the farm work while the men were at the front. We visited Piccadilly Square, and once even went to Buckingham Palace and stood at the front gate where we saw Princess Margaret when she was about seven years old. She waved at us from one of the upper windows, and we all waved back back just before Princess Elizabeth appeared and took Margaret away from the window. It is nice to remember that moment.

We left England for the Cherbourg (Cotentin) Peninsula on D-Day. Our forces landed at Omaha Beach about three miles west of St. Lo, France on June 6, 1944. British, Canadians, and Australians each had their own landing sites in order to engage German forces from as many directions as possible. When my ship arrived at Omaha Beach, we were looking at countless ships, landing crafts, barges, and many downed planes. Army landing crafts were making countless trips ferrying personnel across rough surf stirred up by all the wind and activity. On D-day plus 2, my company of the Chemical Corps, was among the last of the invasion force to hit shore. Unless poison gas was suspected, ferrying infantry into the landing zone and the wounded back out to the hospital ships in front of us was highest priority. From on board ships we watched while men were fighting above a high embankment with mortar flying around them while German shelling continued on top of the hill. Germans used some wooden bullets that splintered when they hit and did a lot of damage. I brought some of these bullets home with me.

When I waded ashore, there was some enemy fire, so I thanked God it was fairly dark. The sky was still light enough to reveal a dead civilian entangled in some wire about 20 feet above the ground. I am still haunted by that sight, wondering how in hell he wound up in that mess. Did he jump off the cliff to avoid enemy fire, or what? I never found out, but it sticks in my mind. A few minutes later, someone from a completely different unit spoke to me. He recognized me and said, “Fancy meeting you here.” It was one of the Schumckal boys from Hannah, which is only five miles from Kingsley. I was so surprised to see him, I only said, “The bastards are up there. See Ya,–or not.” That is all we said to each other and I never saw him again.

There was still a lot of firing above us and Sargent Jerry Lord said, “I hope they are shooting at each other and not us.” We had nothing but our detection equipment to fight with, but I wouldn’t have minded throwing my gas mask at them. My company marched to St. Lo after it was secured. Fighting had been furious even before my company landed at Normandy.

We were at St. Lo until well into July, 1944. While there, my training continued with officers and a few other enlisted men. The officers, looking like they were sixteen, were supposed to know everything. While looking for someone to lead the group in training, my buddies recommended me to conduct classes. In most sessions, an officer would say, “Could we have Private First Class Webster step forward?

I often said to my friend, “They must be in love with me.”

After the supervisor, a major or some other rank, assigned me to teach, I usually started by saying something like, “Good afternoon officers, gentlemen, Colonel Bradford.” There were a lot of things that I wanted to say like “Sure glad you’re overweight,” even though they were guys like you and me. But I got up there and said, ”Colonel,” there was a swath of officers, “I probably can’t tell you any more about chemical warfare than you already know, because your training has been much the same as mine.” It’s here where I say, “ Chemical Corps started because—Karl (a pseudonym for Hitler and all the German people), being the bright man that he is, he might, one day, want to fight in a different way. So I am going to take you through this and if you have questions to ask, ask them and if I know the answer, I’ll tell you. If I don’t know the answer, then neither of us will know. “

You need a little wise crack in now and then. It makes it better. I had to tread lightly. Those guys were Lieutenants, Majors, Colonels, and here I was a private first class trying not to make them feel that I thought I was smarter than they were.

![Image of St. Lo after conflict. Image made publicly available by the German Federal Archive, Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1994-035-17 / Vennemann / CC-BY-SA [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons.](/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Bundesarchiv_Bild_146-1994-035-17_Frankreich_Saint-Lô_zerstörte_Gebäude-300x213.jpg)

Some of my company left for Liege, Belgium on the Red Ball Line Highway when the Battle of the Bulge began. Word finally came that I, and what was left of my company, were to leave St. Lo after a short stay at Le Havre, and then on to Camp Chesterfield in Aachen, Germany after it had been taken in the Battle of Aachen on October 21, 1944. While there, in November, I had numerous colds, but no one knows what brought it on besides the cold and windy weather. I became weaker and weaker until even standing guard duty became difficult. I must have let the winter weather and constant cold get the best of me. I do not remember quite how I came to be discovered half under a parked vehicle, but I was soon recognized and someone acknowledged that I wasn’t a drunk. An officer soon took me to see a doctor who diagnosed me with double pneumonia. The doctor also found severe irritations in my nasal and pharyngeal passages. It seemed strange that my symptoms mimicked the effects of benzyl bromide, one of the many poisons that I was sent to detect. Headquarters sent me to recuperate at the 114th Hospital in Echternach, Luxembourg, just south of the German boarder. My recovery was slow, so when most of my company left to support other groups in the Pacific Theater to fight the Japanese, I was left behind.

While at the 114th, enlisted men such as myself, often ate with officers at the chow hall. One day, I met a colonel whose name was Neil Brownson. We were really surprised to see each other as Neil was the son of Doctor Jay and Effie Brownson. Neil had also grown up in Kingsley in the big white house just north of the present day bank building and after the war went on to practice medicine at Munson Hospital.

For a short time, while still recovering from pneumonia, I was sent back near St. Lo to stay at Shad Coterie Chateau. Not far from St. Lo and near Caen, France, I was able to do some sight-seeing. There was a small cemetery nearby that had a recent burial site, oddly separated from the rest of the sites by four low walls of stones. The only information available was that an enlisted man was purposely buried apart from any other servicemen. He had decided that he wanted out of the service and refused any alternative assignments—even a rear-echelon position. When he and his squad were sent on a forward reconnaissance, he attempted to surrender to advancing Germans. His squad was quickly overrun and most of the men were killed. His burial was kept separate due to his dishonor.

Other men disappeared like a young fellow that my buddy and I were in charge of after he shot his Sergeant. We were ordered to settle him in a cold tent with little warmth, but we later supplied him with blankets. Before he was scheduled to ship home to be tried for murder, we let him loose to be free to go to chow and walk around camp. He asked for us before he was taken away. My officer said, “Don’t forget. This is war. A lot of things happen in war. Records will probably show, ‘He died in war’”.

When I had recovered enough to be able to work inside, my main assignment was to The Postal Service, for the rest of the war. The Chemical Corps still claimed me for short durations as a student or as a trainer.

It is hard for me to retrace my experiences and various locations in Europe after 69 years. My rear-echelon work in Europe had no fixed locations or duty assignments even during battles because: 1.The services peculiar to the Chemical Corps were not in demand. 2. Our company personnel were loaned out to other units helping in any way we could. 3. In addition to varied duties, we attended chemical decontamination classes, and each one of us shuttled at least once between England and mainland Europe. 4. Unless hospitalized, people, like myself in physical recovery, trailed a few days behind each allied advancement through France, Luxembourg, Belgium, Germany, and Austria.

Late in 1945, prisoners were treated with less suspicion as they were glad to be out of battle, had food to eat and a dry place to sleep. While stationed at Kassel, which is about half-way through Germany, we were in charge of German prisoners. Whatever the officers wanted, prisoners would run and fetch it as they were happy to be out of the midst of the battle. In early May 1945, I followed the advance into Austria while still filling in as part of The Postal Service. One morning, just outside our camp I saw what looked like a whole army. There were thousands of men and I thought, “I hope they are not surrendering. If they are, how in hell are we going to feed that many?” Tanks and other armored vehicles came with them. They wore the strangest looking uniforms that I have ever seen. Some had big fancy tall decorations on their helmets and short skirts. We wondered, “How do they expected to stay warm dressed like that?” They did not understand us and one spoke in Italian, while others pantomimed that they needed more food.

A fence soon separated them from us and we were warned to keep our distance from them, but we asked if they wanted some of our rations of stew and bread. They held their hands out like they didn’t know what it was we were asking. We hollered back, “Stew”. We must have looked imposing, while they must have mistook “Stew” for a command unknown to us, because a huge avenue quickly formed through their ranks. They were most grateful when we tossed stew soaked bread over the fence instead of opening fire on them. One of our officers asked for an Italian interpreter and a man came forward and was told that they hadn’t eaten in three days. Word went out to the nearby village that more food supplies were needed which were soon brought for them. Lousy, starving, and not clothed for the weather, they were in horrible shape. After they had eaten, we watched as their clothes were burned, they were hosed down, deloused and re-clothed with army fatigues that had “POW” printed on the backs. I have often wondered how the supposedly Italians traveled from their battle front with all those strange uniforms. Were they really Italians forced to fight for the Nazi’s or were they Germans that changed their clothing for any uniform they could find hoping to hide their true identity? Why did they respond so strangely to our shouted word, “Stew”? Our command never gave us any information about who they were.

On May 7, 1945, I was reading a letter from Mrs. Dorothy Wood, the mother of a school chum, Bill Wood, whom often wrote me most welcome messages of news from home. An army buddy burst in with the news, “Well the war is over here, now we are soon off to Japan.” Three days later, I was called into the camp office and as I was walking to the door, I thought, “Well here we go to Japan.”

Seated was a major who said, “How are you , soldier?”

“Okay. A little weak, but okay.” I said.

He said, “Well we have here a statement from Supreme Headquarters Allied Forces Europe , that you are married, have a child, have been awarded four service medals each for the four battles in which you have been involved: Normandy Invasion, St. Lo, Aachen, and The Ardennes Counteroffensive. You have earned enough points with three years served—we are sending you home instead of the Pacific. You and most of your company will ‘Step Aside’.” Those words were never more welcome. I said my goodbyes to my buddies and especially my good friend, Jerry Lord, before I left. We shook hands for the last time. Months later, I went looking for him and found out that after the war, he was transferred to Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, but his plane went missing somewhere over our home state. It seemed a hell of a way to die after going through the whole war. To this day, losing my buddy, is still my most painful memory of the war.

I put my duffel bag over my shoulder, got on the truck, and left for Camp Chesterfield, Holland. Traveling through Germany in 1945 by train with more than 140 box cars day and night, all you could see was devastation of that country. We finally arrived in La Harve on the coast of France and left for the USA. We did not stop in England, just the same journey in reverse of my trip over there—eleven days of water, water, and more water, but what a great sight was the Statue of Liberty all lit up in the New York Harbor. The band was playing while I stood on the deck with my mouth hanging open.

A few days later, I left by train for Chicago to meet my wife and son, Dennis. I had learned of his birth when on leave in France. My brother-in-law and sister, Ed and Norma Clous, came to Chicago and helped me and my family move home to Kingsley. When we walked through the door, greeting me all across the back wall of the kitchen, was was a big sign written, “Welcome home, Daddy.” When I left the U. S., I was newly married, childless, and going to Europe to fight for an undetermined amount of time. Thousands of people in terrible conditions were still fresh in my mind along with good and bad deeds done by most everyone involved. Now, I had to wipe that slate clean and learn to be a husband, father, and provider.

After coming home, I played piano in a band called Satler’s Night Hawks, helped my brother Carl paint houses, and then was employed at Parts Manufacturing in Traverse City where my father worked. We both became union Stewards in jobs that lasted many years. I was the last man out before the doors were closed for good. Out of work, I went job hunting in Chicago. I had a couple of good offers, but before I accepted anything, Melvina called to tell me that the personnel office at the State Hospital in Traverse City had called about a job opening. So, I said goodbye to Chicago, drove five hours home to Kingsley, and the next morning went to the hospital and applied for that position. I was hired and worked there for twenty five years.

Brenda Wolfgram Moore was a resident of Kingsley, a local historian and genealogist, who passed away in 2014. Peter Newell is a good friend of Floyd Webster’s, and a published author. Newell is currently working on another oral history of a Kingsley resident who served in World War II.