Swimmer’s Itch plagues many Michigan lakes. Children are especially affected as itchy red bumps appear on legs and torso, soon after swimming. Little can be done to alleviate the itching—the old remedy of baking soda is probably as good as any. In a few days it disappears on its own, anyway.

Image made available on Wikimedia Commons by the CDC/ Minnesota Department of Health, R.N. Barr Library; Librarians Melissa Rethlefsen and Marie Jones, Prof. William A. Riley. This media comes from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Public Health Image Library (PHIL), with identification number #8556.

The cause of the itch has been known for many years: a tiny parasite inhabits snails of the lake, shedding them into the water on warm summer days. These cercariae are neither bacteria nor viruses, but a member of the flatworm phylum. In short, they are worms. Many years ago, at the University of Michigan Biological Station, I remember seeing them emerge from snails confined to a watchglass under a low-power microscope. Compared to other such water creatures, they weren’t that small. You could see them with your eyes if you cared to look.

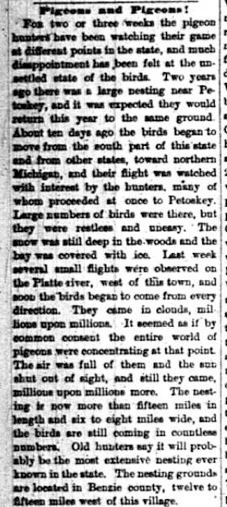

After leaving the snails, apparently tired of the pace of life there, they swim around looking for a secondary host, frequently diving ducks such as the Common Merganser. Finding one, they bore through its skin, somehow finding one another in the circulatory system to mate (I believe the animals are bisexual). Afterwards, they migrate to the digestive tract where they produce eggs ready to be shed into the water with the duck’s feces. Gaining the freedom of open water, they locate snails to infect, thereby completing the cycle.

We humans should be bystanders to this unwholesome series of events, but for one thing: the cercariae mistake us for ducks. Only after entering the outermost layer of skin do they realize their awful mistake, but it is too late for them: our body’s immune system reacts to kill them off, that response leading to an angry, itching bump, swimmer’s itch.

Various methods have been used to control the pest. At least two of them have been tried locally: copper sulfate and removing duck populations. Copper sulfate kills snails, one of the hosts, but that method has been largely abandoned because it is not particularly effective in the long run and because it has harmful effects on other life.

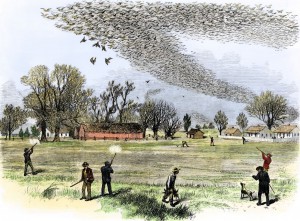

Getting rid of ducks is easier said than done. You can’t shoot them all—after all, there are game laws and many of us (including me) like them. One technique is pyrotechnics. At first I thought this had to do with firecrackers and bombs to drive away flocks, but that is not exactly so. As applied to duck control, pyrotechnics has to do with firing a variety of noisemakers including propane cannons, thunderboom sticks, and bird bangers. A loud noise sends flocks flying, no matter what the source.

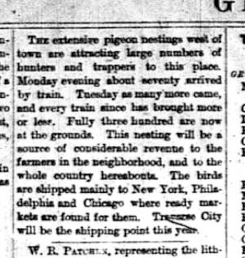

Glen Lake has tried this method for several years with inconclusive results. The Glen Lake Association on its website reports the itch still is bothersome, but not as bad as at Higgins Lake, where no such control has been attempted. For some persons, the intermittent detonations may prove as annoying as the itch.

A friend whose family owns a cottage at Glen Lake for many years tells me that the lake has always had a swimmer’s itch problem. The red, itching bumps were a rite of summer. Usually, they do not discourage children to the point they will not go in the water. Swimming and splashing in the water are just too much fun.

There are some things you can do to avoid swimmer’s itch (aside from scaring ducks and poisoning snails). There is some evidence that the cercariae are to be found more often on sunny, warm days, especially close to shore. Onshore winds drive them close to beaches where children are likely to play. Shorter swimming sessions might make infection less likely, too. Unfairly, suntan lotions often contain compounds that attract the itch organisms. Parents cannot catch a break—they must protect their children from the sun and from annoying creatures in the water. Apparently you cannot do both at the same time.

My reaction is that we will probably have to use these common sense measures of control—at least for now. As a duck lover, I hate to see flocks constantly chased off lakes by loud noises. Besides, how long will it take for them to get used to booms and pops? After all, the sounds of traffic in New York City used to be so quiet that they were ignored in 1850. Now, in 2017, it is no different, only we accept 70-decibel noise as normal. Wouldn’t the ducks do the same as we did—learn to ignore the noise?

Richard Fidler is co-editor of Grand Traverse Journal.