Did you ever ride down to Traverse Point and back by way of Old Mission, all in one summer evening and night? If not, one of the freshest, most charming pleasures awaits you that ever your life held. Give your imagination the rein for a little space, and in fancy take the trip with us, to-day.

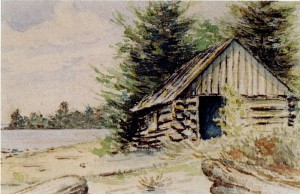

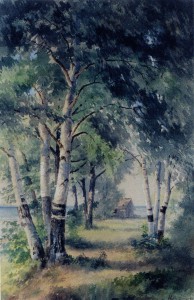

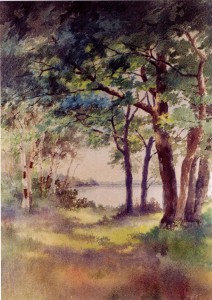

It is verging on five o’clock p.m. when we leave Traverse City. The sun is dropping towards the western hills, and sending long level golden beams into the eastern belt of pines and oaks as we leave the town behind, and sweep around the bight of the bay to the Peninsula. The bay is a misty blue with long lines of sparkling waves rushing shoreward, for though the air is warm with a languid, luxurious August heat, there is a brisk breeze from the northwest that sweeps through it—cool, bracing, exhilarating. In a few moments the town is dim behind us,–white houses, mill stacks with their plumes of smoke, church spires, and the castle-like walls of the asylum all melting together into the dim outlines. With swift and steady stroke our horses’ hoofs fall upon the hard, level road, and the speed of our going, with the rush of the wind in our faces, makes us feel as if it were wings instead of feet that are bearing us onward. The pines and cedars have closed in on both sides of the road. The air is spicy with resin and balm. All the little nooks are ablaze with goldenrod, blue with wild asters, or white with yarrow, that “dusty beggar, sitting by the wayside in the sun.” Now and then, a pretty clearing opens on the right, with a cosy white farm house set down in its bit of orchard, or green meadows, with a bright bed of flowers by the door, and beyond, fields of corn standing stately and tall in serried ranks, like soldiers on parade. Then the wood closes in again with its sweet, dark greenness. To the right it is close and dense. To the left is always the bay, so near we could toss a pebble in it through its fringe of birches and cedars. The wind freshens and the white caps dance out beyond the pebbly shallows. The crisp waves run up the beach and fall with a musical crash on the shore. Marion Island begins to loom large and green ahead. The little haunted island shows its fringe of bushes and stunted pines more clearly. The bay shore begins to take a great curve. The islands are abreast and then drop astern. The sun is shorn of his beams, and, a great glowing ball of fire, drops below the purple hills. A sudden, dewy breath as of twilight and the coming night sweeps out of the thickets. Tall pines stand in stately colonnades along the beach. There is a dock, ancient and wave-worn, running out into the water. This must be Bower’s Harbor, and we look out towards the haunted island, half expecting to see the ghost of the old Sunnyside come steaming out from behind the bluffs as she speeds to her old landing place. But no. Her timbers strewed the beach of Lake Michigan long years ago, and bluff Captain Emory sleeps his last sleep somewhere under these northern pines, and for her there has never been given a ghostly resurrection. On and on, the road sweeps around o the west and climbs a steep way cut on the side of the bluff, so near and so overhanging the water that the spray from the tips of the great green curling waves now coming in falls over us. The stout horses tug and bend to their task, and presently we are out on the top of the highlands, and the world lies open and fair before us, and this is Traverse Point.

What shall we say of it? Here are the beginnings only as yet of the improvement of one of the loveliest spots for summer homes in all this beautiful Resort Region. It is not fair to tell now of what is,–for that is changing so rapidly to the far different what-it-will-be. These pretty cottages rising here and there are only the avant couriers of uncounted others to come. Here is a children’s paradise, where all the summer through the little ones may gather roses for their cheeks, and strength and litheness to their supple limbs. Here—but why foretell? The swift years are telling the story of them both,–beautiful Traverse Point and fair Ne-ah-ta-wan-ta, “placid waters.” What will never change are rose of dawn and gold of sunset, silver glory of moonlight and purple of twilight, misty gray of summer rains and strength of wild waves when the winds send them sweeping in from the northwest in long lines of foam crested rollers, sparkle of blue under the noonday sun and glint of stars in fathomless depths of midnight in heaven above and water below,–a thousand variations of tint and form, of sound and motion, of shadow and light, and all beautiful beyond expression.

But time flies; we must not stop for rhapsody.

Back to the eastward we go and are off across Peninsula. The west is all aglow with gorgeous sunset hues of orange and crimson and dusky gold. There is a strange sense of wide expanse and unwonted freedom. We look to see why, and find it is because there are no fences in this township.

“How beautiful it is!” we say to each other. Here is a wide stretch of meadow land; just beyond it melts into a yellow stubble where the wheat was not long ago; then acres of silvery oats and then again the corn, rustling in the evening breeze, while again great patches of potatoes—green tufts, dotting the well-tilled brown soil, come down to the very wagon tracks. It is a great Acadian garden. The road winds and turns. It seems further than we thought. We must have come out of our way, for part of the time we are surely going back on our former direction. Shall we stop and inquire? No. It is fun to be lost in Peninsula, for we can’t get far away without getting into the water, and we must come out somewhere. So on we go in the fast gathering twilight. We are in the midst of the great Peninsula fruit farms. Far and wide on either side stretch the orchards. Those—green and glossy in the dim light—are cherry trees; they lost their ruby fruitage long ago; these are pears—loaded down, and with their branches propped to keep from breaking, and already the air is getting spicy with their ripening; yonder are plum trees, more purple than the purple twilight shadows with the bloom on their masses of fruit,–and everywhere are apples,–trees gnarled and knotty with age and crimson with clustering fruit,–trees young and vigorous and heavy with golden treasure,–surely the fabled apples of the Hesperides were not so well worthy of fame as these. There are handsome farm houses set down among these orchards. The light is dim now, but we can see and feel evidences of thrift, of comfort, and of substantial competence. Lights twinkle here and there through the trees. The road is hilly now, and we go swiftly up one rise and down another, till soon the road bends again and we sweep out on the East Bay shore. We are at Old Mission.

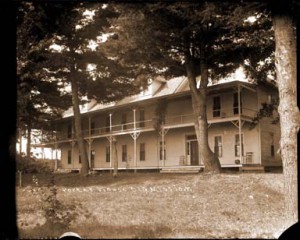

Here we stop for a little rest before we fairly start on our homeward way. We sit under the great maples at the Old Mission house, and watch the far off stars, and the distant lights across the bay at Elk Rapids, and listen to the whispering of the waves down on the beach and the moaning of the wind in the trees overhead, and dream. By and by the moon rises large and fair over the eastward lying hills beyond the bay. There is a path of silver across the water. The shadows of the great trees lie heavy on the grass. The lights in the cottages down at Old Mission Beach Resort begin to go out one by one.

It is time for home going. The good horses are rested and ready for home. Once more their hoof beats ring on the hard, level road.

Down the center of Peninsula this time. Right along the high ridge that is the “backbone,” in the old settlers’ dialect. On either side are deep ravines, dark with shadows. Overhead the trees shake shadowy hands with each other from either side of the way. The farm houses are all dark. The world is dead with silence but for the echoing hoof beats. On and on. At last we rush down a long winding hill road, and out on the level lowlands. To the right, the country with its fields. To the left the beautiful bay sparkling with silver in the moonlight. We are tired of saying “How beautiful!” but are silent and drink in the still loveliness of the moonlit water, the quiet fields, and the shadowy woods.

Another hour, and we cross again to the other side. The West Bay welcomes us with its wind-tossed waves. The village with its white houses stands still and fair under the oaks in the moonlight. It is its silent streets that echo with our horses’ hoof beats now. Forty miles and more of riding between supper and sleep, and such a ride!

Home at last!

——————————————————————————-

Notes: M.E. C. (Martha E. Cram Bates) Bates was an important literary figure of the Traverse area, arriving here in 1862. She married Thomas T. Bates, the editor of the Grand Traverse Herald, working in various capacities for that newspaper over the next thirty years. She especially enjoyed keeping a column in the Herald called “The Sunshine Society”, which entertained children with poems and stories. As an early woman journalist, she helped to found the Michigan Woman’s Press Association in the 1890’s.

Martha Bates was co-author (with Mary K. Buck) of two books, Along Traverse Shores (copies are available at Traverse Area District Library) and A Few Verses for a Few Friends. The present article is taken from the first volume. M.E.C. Bates died in 1905.