by Julie Schopieray, Author, Researcher, and regular contributor to Grand Traverse Journal

Long before women’s skirts were worn above the ankle, and even before gaining the right to vote, Traverse City was the home of a woman who, while remaining a “lady” of her time, took on the challenge of an occupation never before held by a woman. As an active, law-abiding outdoors-woman, she became frustrated by the lack of enforcement of hunting and fishing laws. She saw firsthand the need for a local person to monitor hunting and fishing and prosecute the violators of regulations. In the summer of 1897, she applied to the newly appointed State Fish and Game Warden, Chase Osborn, for the position of deputy game warden in Grand Traverse County. He hired her for the job.

Early rules on hunting in Michigan were not strict. “Bag limits” were basically non- existent until 1881 when the Michigan Sportsman’s Association (MSA) lobbied the state to reduce the season to five months out of the year and limited the taking of fawns and banning certain types of hunting. The state’s first paid game warden position was created in 1887, the job mostly consisting of enforcing game and fish regulations. Wardens were not assigned to every county or region until much later. In 1895 the first real management of the state’s deer herd began with a law which limited the hunting season to a few weeks in November. New laws followed to prosecute violators.

Laws on fishing in Michigan’s waters at the time were mostly limited to those of spearing, fishing during spawning season, and the taking of certain size fish. There were many who chose to ignore these regulations and the sportsmen who did obey the laws felt not enough being done to enforce regulations.

One of these people was Hulda (Valleau) Neal. Born in Ohio in 1854, Mrs. Neal had lived in the Traverse City area since her marriage to James Warren Neal, a Civil War veteran, in 1872. They owned a farm in western Long Lake Township near Cedar Run. They had two children, Emma, born in 1874, and Arthur in 1875.

In the summer of 1897, and at the age of forty-two, Hulda Neal accepted the appointment of deputy game warden. Because women’s roles outside the home were mostly limited to teaching or nursing, and due to the fact that she was the first and only woman in this traditionally male profession of fish and game law enforcement, the news of her appointment spread quickly in newspapers across the country. The July issue of Forest and Stream magazine announced the appointment of Mrs. Neal:

Mrs. Warren Neal of Neal, Mich., has been appointed deputy game warden for Grand Traverse county by State Warden Osborn. Mrs. Neal is forty-two years of age and of medium stature. She says she took her office because she wanted to see the fish and game in Grand Traverse county protected, and that the men do not seem to be able to enforce the laws. These are stirring times.

The Official Bulletin of the Sportsmen’s Association gave this description of the new woman game warden:

Mrs. Warren Neal of Grand Traverse County, Michigan is a duly commissioned county game and fish warden. She is a slender, sprightly little woman in the prime of life with brown wavy hair and honest bright blue eyes. Mrs. Neal weighs 108 pounds, but can row and manage a boat with more skill than some muscular men.

Mrs. Neal’s explanation of how she incurred her appointment is as follows: “Why there was a warden, but he could not come up here and stop the spearing and netting of fish and killing game out of season, and I asked Mr. Osborn, State Game Warden, to appoint me, and he did.”

(Reprinted from the Official Bulletin of the Sportsmen’s Association. From the Women in Criminal Justice Hall of Honor, established by Women Police of Michigan, Inc. in 1991 to honor those women who have contributed to the advancement of women in criminal justice. SOURCE: Criminal Justice and Law Center, Lansing Community College. Also printed in the Women’s History Project of NW Michigan newsletter.)

The best description of Mrs. Neal and her role as the first woman game warden was published in the Philadelphia Inquirer on 15 August, 1897, complete with somewhat stylized illustrations. The article was reprinted in papers across the nation.

Once again a new and startling occupation has been found for the new woman. It is that of game warden, and the woman who distinguished herself by making this brand new departure is Mrs. Warren Neal of Neal, Mich. This woman was appointed game warden for Grand Traverse county not long since, and from the appearance of things she will attend to the duties of her office in a businesslike manner.

The duties of game warden are of such a nature that many men would not care to undertake to fill the place, but Mrs. Neal is a plucky little woman, and she has no fear whatever of not being able to overcome all obstacles. A game warden is supposed to travel all over the county and keep a sharp lookout for violators of the game and fish laws. As Grand Traverse county, of which Mrs. Neal has control, is densely wooded and has many lakes, she will be kept very busy seeking out and bringing justice violators of the law.

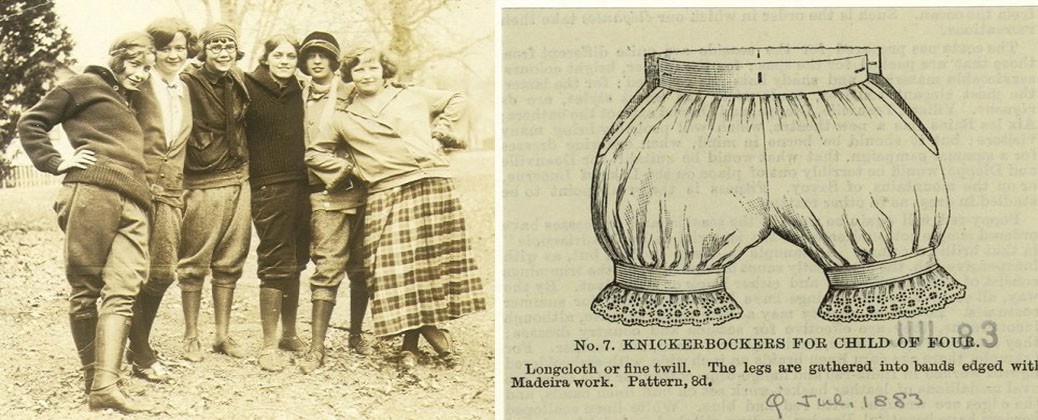

Mrs. Neal handles a gun like an expert, rows a boat and is a skillful woodsman, and she knows every inch of the territory she has to patrol. In order to make her way through the dense growths in the forest land as easily as possible Mrs. Neal has adopted a costume modeled after the much reviled bloomers.

As to the trousers, Mrs. Neal says that she has no desire to be considered as setting the pace for the new woman. In fact, she told the writer she thought every woman ought to dress according to her own ideas of comfort, though for the life of her she could not see why any woman should want a skirt when hunting or rowing. It really appears as if Mrs. Neal is the sort of new woman that has a mind to advance her sex along sensible and health giving lines.

As to the trousers, Mrs. Neal says that she has no desire to be considered as setting the pace for the new woman. In fact, she told the writer she thought every woman ought to dress according to her own ideas of comfort, though for the life of her she could not see why any woman should want a skirt when hunting or rowing. It really appears as if Mrs. Neal is the sort of new woman that has a mind to advance her sex along sensible and health giving lines.

She usually makes a trip over the entire county once a week. When out after the violators of the game law, she rides over the country on horseback, and when she comes to a lake she secures a boat, and with steady, swift oar she rapidly covers her territory made up of water.

She carries a rifle on all of these trips, and woe to the evildoer caught napping, for this plucky game warden is a relentless pursuer of all lawbreakers, and she has brought many of them to justice.

During May the state game and fish warden’s department prosecuted 109 alleged violators of the law and convicted 96, growing out of 149 complaints. This breaks the record for any previous month in the history of the department. All but three of the convictions were obtained for violation of the fish laws, and the majority of these cases were established by Mrs. Neal.

Her skill with a rifle is something phenomenal, and she drops her quarry with the ease of a professional Nimrod. Mr. Neal, who is an enthusiastic sportsman, long ago taught his wife to be skillful with the revolver. Last July when they were in the upper lake region camping he induced her to try her hand with the rifle. He declared that a woman who could shoot so well with a revolver would with practice become a dead shot with the larger weapon. Now, rifle shooting requires a good eye, a steady hand and wrist and a control of the nervous system that very few women possess. Generally the novice fires at a target. Mrs. Neal’s first target, however, was a glass bottle thrown in the air, and at a third shot she struck the bottle, a surprisingly good attempt. Mrs. Neal kept on practicing, and now is so expert that she can hit the glass bottle nine times out of ten.

In addition to her other duties Mrs. Neal carries the mail three times a week to Traverse City for Uncle Sam.

Several other newspaper articles, though much shorter, give a few more bits of information on Mrs. Neal. The Muskegon Chronicle of 9 June, 1897 reported:

She handles a gun with the best of them, rows like an Indian, can track a deer when the old woodsmen can’t and is an all-around athlete of the northern woods type.” The Adrian Daily Telegram dated, 28 Dec. 1897, describes her clothing and riding style: “She wears pantaloons just like those of men and can handle the rifle like a veteran marksman. Mrs. Neal jogs over the country once a week on horseback. When she rides through a town she always sits in the feminine style, but when she reaches uninhabited territory, it is said, she assumes the clothespin style of navigation.

Although there were some who assumed she’d never be able to perform the duty as well a man, Mrs. Neal became locally well known as someone not to be trifled with and would execute her job as well as any man. An article in the local paper shortly after her appointment made this clear. “…she is an active woodsman, a good shot and can give cards and spades to any man in the manipulation of a fishing rod…Mrs. Neal will wage an aggressive campaign against violators of the law…and offenders in her locality will find that she will stand no fooling.”

The state warden position had a term of four years but there does not seem to have been any specific term length for deputies. Mrs. Neal fulfilled the duty of local warden for two years. State laws gave deputy wardens the same power and authority as the state warden and the same power and rights as a sheriff would have– the power to arrest anyone caught by them violating game and fish laws. They were paid three dollars a day for each day spent doing their duty, plus expenses. During her two years on the job, a few articles describing her experiences were printed in the local papers. One was in the Traverse Bay Eagle on 3 June, 1898:

Last night Mrs. Warren Neal, the fish warden, accompanied by another lady, went out on Long Lake, hoping to capture some violators of the fish law. She was not disappointed in the least for as she went into the little lake she discovered a jack light [Note: a jack light is a fie-pan or cresset usually mounted on a pole for hunting and fishing at night]. As soon as Mrs. Neal was seen by the occupants of the boat the light was dashed into the water and the lawless men not being far from shore, jumped into the water and made their escape into the woods. As yet no arrests have been made. Mrs. Neal now has their boat, jack and spear in her possession.

Another article from the Saginaw News on 13 June, 1899 described an incident that seemingly did not go well for Mrs. Neal:

Mrs. Warren Neal, deputy game warden, found out yesterday that all is not smooth sailing in her calling. She rowed out into the lake yesterday to arrest some men who were spearing fish against the law. The men took her boat in tow and, towing her to a lonely spot in the lake, left her stranded on the shore and politely took their leave.

A follow-up article in the Traverse City paper the next day told a slightly different story:

The statement that has been made that the two men who were spear fishing towed Mrs. Neal’s boat ashore and then put their own boat on the wagon, said goodbye and left, is not at all correct. Mrs. Neal says that she saw the lights on the lake, took her son, who is constable, with her, and went in pursuit. The men did not want to give up and when told that they were violating the law, made some wordy resistance, but finally, threw away their spear. Mrs. Neal sprang into their boat and told the constable to take and secure her boat and secure the spear, which he did. She then secured the fishing “jack” and the men rowed to shore, the constable remaining in Mrs. Neal’s boat, but this was not in tow of the other boat. Mrs. Neal declares if she had had her handcuffs she would have secured both men. As it was they offered to ransom their “jack” by paying her $25. The offer was indignantly rejected. It was 3:45 a.m. when the boat reached the landing. Mrs. Neal declares she is going to break up the practice of illegal fishing on Long Lake.”

Mrs. Neal’s term as game warden ended after two successful years of service but she continued to work with the State fisheries by stocking wall-eyed pike in Long Lake for several years, at least through 1909.

Only six months after her appointment as warden, Mrs.Neal was no longer the only women holding that kind of position. In January 1898, a twenty-six-year old Annie Metcalf from Denver, Colorado, was appointed the position of game warden in that state. Both women were well qualified for the job, however, Mrs. Neal held her position longer than Miss Metcalf.

Mark Craw began his career as a deputy game warden in Grand Traverse County in 1899 which put a second person out enforcing the fish and game laws during the end of Mrs. Neal’s tenure. Mr. Craw remained both warden and conservation officer until his retirement in 1945.

Hulda and her husband bought a house on Washington St. in Traverse City around 1904. He worked as a drayman for several years but Hulda did not hold any further occupations over the last thirty years of her life. She passed away on Feb. 9, 1931 at the age of seventy-six. There is no mention of her time as a game warden in her obituary. Mrs. Neal is listed in the Traverse for Women website as one of the Notable Women of NW Michigan and listed in the Women in Criminal Justice Hall of Honor, established by Women Police of Michigan, Inc. in 1991 to honor those women who have contributed to the advancement of women in criminal justice. SOURCE: Criminal Justice and Law Center, Lansing Community College. http://traverseforwomen.com/Herstory/index.htm

The Michigan DNR has applied to have Mrs. Neal entered into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame in 2018.

Julie Schopieray is a regular contributor to Grand Traverse Journal, a researcher to be admired, and author of the fantastic new biography, Jens C. Petersen: From Bricklayer to Architect. Copies of the book can be obtained from Horizon Books, Amazon, or directly from the author.