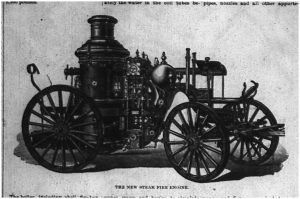

Here are two images of the Queen City No. 2 Steamer, separated by more than 200 years. Traverse City’s second Steamer is still preserved at a location near Lansing, Michigan. Where would you go to view the two steamers? Extra credit if you get both!

Here are two images of the Queen City No. 2 Steamer, separated by more than 200 years. Traverse City’s second Steamer is still preserved at a location near Lansing, Michigan. Where would you go to view the two steamers? Extra credit if you get both!

Join our friends at the Benzie Audubon Club and get outside! On Saturday, December 10, at 9:30 a.m., Carl Freeman will be leading the group in search of waterfowl on Lower Herring Lake. Meet at the Lower Herring Lake public access. Contact Carl Freeman (231-352-4739) with questions.

![Red-necked Grebe with chicks. By Lukasz Lukasik (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons. [Editor's note: Grebes are not found in Michigan. We just loved this photo.]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Podiceps_cristatus_3_Lukasz_Lukasik-300x225.jpg)

By Lukasz Lukasik (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons. [Editor’s note: Grebes are not found in Michigan. We just loved this photo.]

For Antrim County Christmas Bird Count on December 14, contact Coordinator John Kreag (231) 264-8969 or cell (231) 360-0943

For Grand Traverse County Christmas Bird Count on December 17, contact Coordinator Ed Moehle (231) 947-8821

“Christmas from the Archives: Vignettes of Christmas from Traverse City’s Past,” presented by past Historical Society Archivist, Peg Siciliano.

“Christmas from the Archives: Vignettes of Christmas from Traverse City’s Past,” presented by past Historical Society Archivist, Peg Siciliano.

Images of Northern Michigan winter holidays will accompany stories of Christmas happenings from Traverse City’s past. Christmas items from the historical archives will be displayed.

Join us for the program on Sunday, December 18th at 2pm., in the McGuire Room of the Traverse Area District Library on Woodmere Ave.

Old Mission Historical Society will host an “Old Fashioned Potluck Christmas Party & Caroling” at the American Legion Post, 4007 Swaney Rd., Old Mission. Doors, 5:30pm; dinner, 6pm. 231-223-7746.

Recently acquired by the Traverse Area District Library is a slim volume, the Forty-Second Annual Report of the Secretary of the State Horticultural Society of Michigan for the year 1912. The volume contains all the addresses and discussions held at the Society meeting on November 12-14, 1912, in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Topics centered around fruit growing, and included caring for the young orchard, preventing frost damage, watering techniques, and more.

The following selection was an address delivered by Mrs. Edith Rose, of Elberta, Benzie County, Michigan. According to Edith, she and her husband Paul moved to Benzie County about 1890, and there started an orchard. Edith’s concerns had much less to do with the actual growing of fruit than the operation of the farm. She does an admirable job discussing labor relations, racism, and prejudice against women. As an example of the last, Edith’s first name did not appear in the publication, and I was obliged to discover it through the Federal census, Benzie County.

Please note that the opinions expressed by Edith are her own, and not those of any staff member of Traverse Area District Library, or the editors of Grand Traverse Journal. Enjoy Fruit Growing from a Woman’s Standpoint:

“Mrs. Paul Rose, Elberta

Mr. President, Gentlemen and Ladies: Inasmuch as we are supposed to be it, I will show due respect to the gentlemen by addressing them first. When I read the program and saw that I was the only woman on the program, I wondered who the program committee had a grudge against- whether the audience or myself. You will no doubt find before I am through with what I am going to say that I am not a talker, but Mr. Rose is here, and so I will say no public talker. If I had been giving more time to speaking, you see I would have had less time for fruit growing.

Nearly 20 years ago a man and his wife, living near Benton Harbor, packed their household goods, loaded them into a car and started them up north, to Benzie county.

While they were being loaded a rain which turned into sleet came up and ruined everything, so far as varnish was concerned. A superstitious person would have take it as a sign to give up the job, but they were not superstitious so kept on with their work.

In the car with the household goods were two horses, a cow and a calf, a very fine calf. When the engineer came to get the emigrant car, he seemed to have been out of humor (perhaps his wife had not made him a good cup of coffee that morning for his breakfast). He struck the car so hard, it threw the car door open and the little calf fell out. The man with the car asked the conductor to wait for him to put the calf back into the car, only to be told to get in or get left.

As there was no way to let any one know of the predicament the calf was in, she wandered in the freight yards crying for her mama until the next day, when a good German woman took pity on little black bossy and put her in a barn and fed her.

Later the Railroad Co. was notified they would have to deliver said calf to her destination, which they did, giving her a ride in the express car.

Three years later, Black Bossy was a cow, and probably thinking to save the housewife any extra work, skimming milk and churning cream, she gave skim milk. Six months later all they had left of Black Bossy was a beautiful black Poled Angus robe.

When the household goods arrived up north, his wife and their little three-year-old daughter, their foreman’s wife and little daughter, started for the north woods as their friends thought.

When they reached Thompsonville they were notified there was a strike on the Ann Arbor Railroad and no one knew when there would be a train, so they went to a nearby hotel (this was 10 o’clock at night) only to be told it was full. They went back to the depot and found there would be a train in a few minutes, that would take them within four miles of their home. Thinking it would be better to be four miles than twenty as they were then, they took the train which arrived in the freight yards of So. Frankfort about midnight, where they were told there was no hotel nearer then a mile, no bus, no telephone, everything a glare of ice, and two little girls asleep, baggage, band boxes, bird-cage and such things that go with moving.

While deciding the next move to make two jolly traveling men offered to carry the little girls, which removed the greatest trouble, and they all started for a hotel. It probably was the first real work those men ever did. for they did some puffing before getting those little girls where they could walk, but very gentlemanly, saw the comical side of the affair.

The next day was bright and pretty and the husband, thinking to get some word from his little family drove to town, to find them waiting to be taken out to their first home of 80 acres of stumps, brush, and woodland, which was the nucleus around which has been builded [sic] what is now known as the Rose Orchards. There my life work has been put in helping to make them a success.

Fruit Growing from a Woman’s Standpoint

To talk on this subject, I will have to refer to our work, as it is all I know. What we have done, all things equal, others can do. A person said to me the other day, “Every woman can’t do what you have done.” Perhaps not, but they might improve on my work. It wouldn’t be best for every woman to engage in fruit work, as there are other lines of work for us to engage in. Just now we can vote and perhaps some day, hold office [editor’s note: Perhaps Edith means within the Horticultural Society, as general election voting was not passed in Michigan in the 1912 election. The measure lost by 760 votes]. I heard Prof. French of Lansing, say, “Men do not do their work haphazard now days.” In speaking of the fruit work, he said, “They spray, prune, pick, pack and market their fruit with brains.” I believe we have brains and certainly the gentlemen think so or they wouldn’t have given us the right of elective franchise, and thereby removing from us the stigma of mental weakness and taking us from the ranks of idiots, imbeciles, Indians [sic] and criminals.

Fruit growing is very interesting, in fact it is fascinating. You plant the little tree, watch the buds start, then the blossoms and later the ripened fruit. How well I remember our first crop of cherries. Mr. Rose said to me one day, “Get a little pail and we will pick our crop of cherries.” There were less than four quarts of them, but we were as proud of that crop as we ever were of thousands of crates in later years. To a woman who wished to take up this work or to one who by circumstances seem compelled to do something of this kind, by being left with a little family and perhaps a few acres of land or a life insurance with which to buy a little farm, I would say by all means, plant a few trees, not too close together and between the rows of trees, plant some variety of berries that will come into bearing early and help pay the expenses of growing the trees and of the family.

It may be a little hard at times, but wouldn’t it be harder to live in town in a stuffy tenant house and take in washing or sewing and live up the insurance, besides depriving the children of the fresh air and the pleasure they would get from helping mama, until they will become a part of your work and will lend a hand to help put one of them through agricultural college and then come home fully equipped to take the care from Mother’s shoulders?

A woman can plant a row of trees just as straight as a man. There are trees in our orchard that I helped to plant 19 years ago, and they seem to grow and bear just as well as those planted by the men. A woman can spray if necessary. My experience has been that there is no part of the fruit work that a woman can not do if she will study and use good sound sense, unless it is to plow, but I think she can hire that done all right.

A wife should familiarize herself with her husband’s work so that she can direct it, at any time, during his absence, and then if she is left alone she won’t be handicapped by having her help say, “She don’t know anything about it, she won’t know whether it is done right or not.” I have never had a man or woman refuse to do the work as I told them to. Mr. Rose has been gone a great deal of the time during the growing of our orchard. At first he would dictate and I would jot down a routine of work to be followed during his absence but that has become unnecessary years ago, as we have had the same fore man for a number of years and he understands his part of the work as well as I do mine.

I have had help in the house most of the time, which has left me quite free to follow our chosen profession, Horticulture. Of late years most of my work has been in overseeing the pickers or packers. I have handled white labor in Indiana in raspberry work. I have assisted Mr. Rose in Alabama with his negro laborers, in the straw berry fields, and of course nothing but white labor on our farm up north. Some women may say, I can’t handle the laborers; perhaps a few suggestions here in regard to this part of the work might help some of the wives of these young students, to have more confidence in their ability to help their husbands in their life work. I keep my help in the house from one to three years. When I hire my house keeper I tell her just what I want her to do and what I will pay for the work and there is never any trouble over the work or wages. Always direct the work in the house or packing house.

If your help knows there is some one around to direct them, even if they understand what they are to do, they will go at their work with more interest. You can keep your help better satisfied and keep them longer, by having your work well systematized, and let them think they are expected to carry out their portion. A worker likes to know they are appreciated and a kind word is a little thing but will work wonders sometimes in accomplishing better and more satisfactory results.

We have had as many as 85 packers in the cherry work. We have never missed but one morning of being there when the seven o’clock bell rung. Don’t ever leave your help alone, they will not work as well. Mr. Rose has often said to me when I did not feel able to go to the packing house: “Can’t you bring your rocking chair and sit where they know you are and where you can dictate the work?” Be very firm and decided with the workers but don’t nag them.

In Alabama I have started to the field with 125 negroes following and joking about their little Boss, “She don’t carry a gun or club.” When Mr. Bose started his berry work in the South, the Southerner said, “You will have to carry a gun or club, for the nigger will have to be knocked down a couple of times before he will work good.” We never had any trouble, kept our help, picked our berries in better shape than some of the fields where they worked their help at the point of the gun. We loaned our negroes one day to an adjoining berry grower. During the day Mr. Rose and I went over to see how they were getting along. When we came near where they were picking berries they expressed a delight at seeing us and when asked how they were getting along, said : “We don’t like this boss. He carries a gun. We like you-alls better.” We assured them that the boss would not hurt them if they worked all right, and then we started back. We had only gone a half-mile when we looked back and there came every one of our negroes. We stopped and when they came up we persuaded them to go back and finish the day, but they said : “No, sah ; we will work for you-alls but we don’t work over there no more.” We saw how they felt about it so told them, “All right go back to their cabins and work for us in the morning.” Kindness, even with the negro, got our work done better than a club.

We never hire our day help for any one piece of work. Then they can not complain if they are changed from one job to another, if I need more packers, I call them from the pickers and if the foreman needs more pickers I send the packers out to help him. We have had girls work 8 and 10 years in the fruit work. They enjoy it and will plan from one year to another, what they are going to do, and have their money spent, in their minds, a year ahead. Always be interested in each worker, study them to know what part of your work they are best adapted to. You may have a person that seems a failure at one thing and may make a splendid hand at something else. Our foreman brought a man from the orchard to me at the packing house and said: “Can you use him here, I can’t use him in the orchard. I set him to nailing packages, and he did fine work the rest of the season.

Just a word to the woman that has some money to invest and contemplates launching out in fruit-work. Be careful in selecting a location, if possible get near enough some town or shipping point where you can easily market your fruit and where you can get help to pick it, and don’t plant too extensively until you are sure you can handle the business, and don’t expect to have time to read stories, papers, call on your neighbors or embroider during the summer months. I heard a joke on a man who bought some land in Florida, unsight and unseen. After the bargain was all made and the price paid he thought he would go and see his new farm. The land shark took him out in a boat and after paddling around awhile said : “Your farm is under here ; when you get it drained it will be all right.” Don’t buy land unsight and unseen. Let the men do that. We women may be easy but there are others.”

The entirety of this work is available online for download: https://books.google.com/books?id=1dpJAAAAYAAJ

Amy Barritt is co-editor of Grand Traverse Journal.

November 11, 1896

Well after midnight Fire Chief Dupres, Alfred Waterbury, and Night Watchman Allen Grayson stood shivering in a brisk southwest wind that would ordinarily send them inside after a few minutes. Tonight, however, something seemed wrong: a dull yellow light flickered to the northeast of the Cass Street fire station where they had gathered. It danced on the thin crust of snow that covered the street in front of them, the same flicker they had all seen so many times before. Fire!

The alarm was sounded, a pealing of bells in a specific pattern that alerted firefighters to the location of the fire. It was in the direction of Front Street and Park, a place where frame buildings stood side-by-side, an invitation to a catastrophic spread of flames. Hitching the fire engine to the waiting team, firemen worked frantically to let the horse collars come down onto the horses’ necks; the rest of the harness was in order in less than four minutes.

Meanwhile, the fire within the steamer was turned up full blast to ready the engine for its pumping duties to come. As the men left the station upon their new engine, Queen City, the horses’ breath raising clouds of steam in the cold, they congratulated themselves on their quick exit. The steamer was new to the town, but they had practiced hard to get away fast, and that practice had paid off.

No more than two blocks from the station, they came to a stop in front of the Front Street House, a large wooden three-story hotel that dominated the south side of the street. Already flames and smoke billowed from the roof in places, the worst of it came from the part of the building that connected the large building on Front Street to the smaller frame building behind it by the alley. So quickly had the flames spread, the firemen doubted they could save the building.

Already persons could be seen scrambling out the windows on the first floor, most in their nightclothes. One brave soul hoisted himself out from a third floor window, making it somehow to the second story, and then dropping to the ground. A little girl, contracted into a ball in fear, rolled off the edge of a roof, only to be caught by a fireman. In all thirty people made it out of the fire: one did not. Ed Newberry, a Swedish hotel porter, was found later, his dog beside him.

As predicted, the fire swept through the frame stores and saloons on the south side of the street, first the hotel, then a drug store within it, Broesch and Sons meat market, C.A. Cavis’s cigar store, Hiram Cook’s grocery, then a barbershop, and two saloons. Next, a large two-storied structure, the Rich & Hallberg building caught fire, one of its walls coming to rest against the brick Tonneller building. Four firemen were caught under the burning timbers, somehow escaping without serious burns. It was here the battle line would be set up to block the advance of the fire to the west. In the end, the line held.

One of the most gallant soldiers in the fight was the steamer Queen City, which performed magnificently, pouring water onto the flaming wall in a continuous stream, extinguishing the fire. It was backed up by the city’s water system. Unbelievably, nineteenth century hydrants and water mains performed without failure. Afterwards the newspaper would remark about the competence of the fire department and the water works in delivering water where it was most needed.

Even so, the blaze spread to the other side of Front Street. In what some described as a flaming arch reaching from one side of the street to the other, buildings on the north side began to catch fire. One by one they succumbed until they encountered Julius Steinberg’s brick opera house. Father Julius Steinberg and son Aleck as well as employees of the dry goods store attached played streams of water everywhere to cool the building. As cornices burst into flame, they hastened to put them out. In the end, though gravely damaged, the dry goods store and opera house were saved.

In fact, the city downtown was saved. Later, everyone remarked that the direction of the wind made all the difference, the fire starting at the Front Street House (or possibly the drugstore within), a location at the east end of the business district. The southwesterly gale-force winds drove the fire primarily to the east, keeping it away from the busy area of storefronts to the west. Credit also went to brave firemen, the fire engine that performed flawlessly, draymen who offered their services free of charge to those having to move store goods, the efforts of businessmen like Julius Steinberg, and ordinary citizens who did their part to help. One business owner, Mrs. E.M. Daniels, was singled out for her bravery in removing her grocery store stock and relocating it nearby at the peak of danger. Another citizen saw the glow of the fire from several miles away, and, suspecting the downtown was ablaze, drove to town just in time to save the merchandise in his sister’s store. There were heroes everywhere to be recognized.

Upon the rising of the sun the next day, the scene was horrific. Fourteen stores had been burned to the ground. More fortunate ones standing on the north side of the street suffered the ravages of smoke and heat, smudged with soot, with gaping holes where glass used to be in their front windows. Black charcoal, square nails lying on the ground, broken crockery, and a few other things resistant to the fire littered the ground. The Grand Traverse Herald remarked that it was the most serious fire that ever visited the city, and, indeed, it was.

November 6, 2016

Students of history sometimes receive unexpected rewards. For some time I had observed that the space across the street from Horizon Bookstore was being excavated to make way for a new building. Whenever the ground is torn up in the downtown area, you can count on interesting things being uncovered. Just two years ago, for example, West Front was repaved, that resurfacing job exposing Nelsonville, Ohio pavers, a brick that covered the road in years past. Now, seeing the earth in neat piles alongside the trenches, I had to go over and inspect the work.

I had something specific to look for. In 1896 I knew a great fire had leveled half a block of frame buildings on the south side of Front Street, the fire extending through the area where the digging was now taking place. Would there be any sign of the fire? Would there be charcoal buried down under?

The day is Sunday and all work had stopped on the excavation. A gentle wind fluttered the yellow ribbons warning passers-by to keep away, and enforcers of a “No Trespassing” sign were nowhere in evidence. In a quick yet fluid movement I ducked under the ribbons and stepped into the trench made by a shovel standing nearby. Nothing revealed itself at the surface, but a foot-and-a-half down there was a streak of black punctuating the beach sand that made up the soil. Bending down to pick some of it up, I sniffed at it and let out a small cry of joy: it was black charcoal from the fire.

It did not take long to find other things: broken window glass, two square, weathered nails, and bits of crockery, one of them big enough to read the name of the maker. Evidence of the fire was everywhere: How I wished I could sieve the pile of dirt to find more relics.

Picking up a piece of crockery, I felt a sense of connection to those living at these shores of Grand Traverse Bay at a time before automobiles, before radio, before television. Looking at the bottom of what could have been a bowl, I made out the maker: Meakin Ironware. A quick search revealed that the Meakin company, founded in England in 1851, had produced it more than 120 years ago. Somehow these ceramic shards survived the fire of 1896: people had handled this vessel, perhaps admired it, and then that awful thing happened. What they had lost now I had found. In a way that made me a participant in the event. History does that that to us: it weaves our own lives into the tapestry of the past.

Editor’s note: The Queen City fire engine described in the article may be seen at Fire Station Number 1 on Front Street.

Author’s note concerning this article: The description of the fire came from an extensive account in the Grand Traverse Herald. Reading the article carefully, a researcher can write a description like this:

Well after midnight, Fire Chief Dupres, Alfred Waterbury, and Night Watchman Allen Grayson stood shivering in a brisk southwest wind that would ordinarily send them inside after a few minutes. Tonight, however, something seemed wrong: a dull yellow light flickered to the northeast of the Cass Street fire station where they had gathered. It danced on the thin crust of snow that covered the street in front of them, the same flicker they had all seen so many times before. Fire!

Upon casual inspection it seems that the author has drifted perilously close to writing fiction: How could he know that three persons gathered in front of the fire station early in the morning? How could he know about the wind, its direction and speed? How could he know about the yellow light to the northeast that turned out to be the fire? The snow?

The answer is that the Herald account had references to all of those things. Far from creating an imaginary world, the writer only wove facts together in a manner that gave the scene life and interest. This kind of historical writing is frequently done nowadays. Seabiscuit, a tale of a famous racehorse, and Isaac’s Storm, the story of the Galveston hurricane of 1900, are just two examples that have become popular in recent years. The advantage of this approach is that it makes history come alive—often in contrast, to stodgy description in the traditional style.

From time to time the Journal will present stories told as an exciting narrative. Perhaps you would like to try your hand at it.

The Gamewell system of fire alarm boxes was installed in Traverse City in 1881, one of only 250 cities that had them that early. Each box could send a message to a central dispatch board which gave the location where the the box was activated. Currently one box remains–on exhibition–at a place readers might readily guess: Where is it?

“Why” questions in science often find ready answers. Why do we have night and day? The Earth turns on its axis. Why do we have seasons? The tilt of the Earth in its path around the sun. What makes the wind blow? Solar warming of the atmosphere. The physics and chemistry of a situation provides us with answers.

Sometimes “why” questions are more difficult. Why are oranges orange and apples red? Why do birds migrate? Why do leaves change color in the fall? Those questions do not depend directly on physics at all. Do they even have answers?

In the case of leaves changing color, there actually is an answer based on physics and chemistry. As the days shorten, plant hormones cause a layer to form in the leaf stem (an abscission layer) that cuts off water supply to the leaf. Leaf cells with chlorophyll die off, that green pigment rapidly degrading. What is left are more resilient pigments, the yellow carotenes and the red anthocyanins. Trees turn red and orange and yellow and, Presto! We have explained why leaves change color.

But another “why” question remains: of what advantage is it to the tree that leaves change color? Here evolutionary biologists wage pitched battles. Is color change somehow “adaptive?” That is, does it have something to do with the tree’s survival and reproduction? Or is it just something that happens, unrelated to those things?

Though relatively ignorant about these matters, I tend to cling to the belief that some things “just happen.” They have nothing to do with enhanced survival and reproduction of species. The question “why” is only an expression of our human intelligence, ever demanding explanations for phenomena that have none.

I could be wrong about it—and sometimes I wonder how anyone could ever prove conclusively certain traits are adaptive. Is that because my own nature causes me to lean one way or the other? Is that very quality adaptive? Understandably, those concerned with such questions are prone to headaches. I hope you are not so afflicted.

Richard Fidler is co-editor of Grand Traverse Journal.

Your Editors can hear your plaintive cries, “Enough with the dessert recipes! What I really need is an early 19th-century way to spruce up my holiday table!”

To the rescue is the Herald Century Cook Book, published by the editors of the Grand Traverse Herald, predecessor to the Traverse City Record-Eagle, in 1900. No need for expensive flower arrangements! Be carbon-friendly with these two salad garnishes: Radish Roses and Celery Daisies. We imagine these would be a lot of fun for a small party to make together, children too, with proper supervision. Send us a photo of your “edible decorations,” and we’ll publish it in the next issue of Grand Traverse Journal.

“Radish roses are made by taking small, round, red radishes and cutting through the surface with a sharp pen knife in sections, leaving enough uncut at the bottom to hold them together. Put them in cold water, and the cut portions will curl backward like the petals of a flower, the bright red contrasting with the white center.

Celery daisies are made by cutting the celery stalks into inch lengths, then with a sharp knife, cutting the stalk halfway down into slits, then again across these slits. Throw the pieces into cold water, when, in the course of a few hours, they will curl back to resemble the petals of a daisy, and the likeness may be further carried out by placing a tiny round piece of the hard-boiled yolk of an egg in the center of the celery.”

Sunday, November 20th at 1pm, Susan Odom of Hillside Homestead, nationally known expert on early twentieth century cooking, kitchens and small-scale farming, will address the Traverse Area Historical Society and all attendees on the art of running an early twentieth century farms. Come pick up some tips for holiday cooking! Event will be held at the Traverse Area District Library, 610 Woodmere Ave. in the McGuire Room.

Sunday, November 20th at 1pm, Susan Odom of Hillside Homestead, nationally known expert on early twentieth century cooking, kitchens and small-scale farming, will address the Traverse Area Historical Society and all attendees on the art of running an early twentieth century farms. Come pick up some tips for holiday cooking! Event will be held at the Traverse Area District Library, 610 Woodmere Ave. in the McGuire Room.

Thursday, November 10th at 4:00pm. Join the Benzie Area Historical Society to “walk a mile” in the shoes of our ancestors with Nancy Bordine. We’ll explore what they wore on their feet, and why they wore them. We’ll ponder the world’s most extreme shoes in terms of age, price, comfort and significance. This entertaining experience may change the way you think about footwear.

Thursday, November 10th at 4:00pm. Join the Benzie Area Historical Society to “walk a mile” in the shoes of our ancestors with Nancy Bordine. We’ll explore what they wore on their feet, and why they wore them. We’ll ponder the world’s most extreme shoes in terms of age, price, comfort and significance. This entertaining experience may change the way you think about footwear.

Vintage aficionado Nancy Bordine has been playing “dress up” with historical clothing for five decades. At last count, she owned more than 550 pairs of vintage shoes. Combine Nancy’s collection with her wide knowledge and contagious enthusiasm, and have yourself a most entertaining history lesson. Held at the Benzie Area Historical Museum, Benzonia.

Meet Cecil H. Dill (27 October 1900-3 November 1989), “The Farmer Who Makes Music with His Hands.” Dill was an aspiring radio performer, who had an interesting talent… the ability to squeeze his hands together and play melodies, mostly of popular tunes of the day.

His parents, Jennie McEwan (d. 22 January 1960) and William H. Dill (d. 22 July 1966), were married in Grand Traverse County in 1899, and spent most of their married life alongside their children Cecil, Dorothy (d. 22 December 1972) and Joan, in Traverse City. According to census records, William briefly operated a farm in Blair Township, probably about 1930 to 1938 or so.

In 1939, William purchased Novotny’s Saloon on Union Street in Old Town, Traverse City, and renamed the establishment “Dill’s Olde Towne Saloon,” which became a favorite watering hole for locals and visitors alike. William had a long career in bartending, with only his brief farming career as the exception.

Like his father, Cecil usually made his living with his hands. During the holidays, he often sold balsam and cedar wreaths, and began taking orders in the end of October, showing the popularity of his work. Over the years, he offered junk removal and other light draying services to the community as well, sometimes partnering with Goldie Wagner (d. 16 April 1986).

But, before his father opened Dill’s Saloon, Cecil was still working the family farm when he discovered his unique musical abilities (I’ll let Cecil tell you in his own words in the embedded video exactly how he developed his talent). Cecil was able to sell his talent to various performers, most notably Ted Weems, the bandleader who would provide Perry Como his first national exposure. Cecil played with the Ted Weems Orchestra in Chicago, and was thoroughly applauded by all those present. According to a Chicago Tribune article of the event, Cecil stole the show.

The years of 1933-1934 saw the height of Cecil’s popularity. He played with Ted Weems, as well as bandleader Hal Kemp. He made appearances at other venues in Chicago and in Hollywood nightclubs. His performances were written up in Chicago and Detroit newspapers, as well as Vanity. He palmed his fame all the way to the National Farm and Home radio hour, and a Universal Pictures newsreel (below), both of which provided Cecil with national exposure.

Although his fame was short-lived, Cecil would continue to play throughout his life, showing up various variety events in Traverse City. Cecil’s Universal Pictures newsreel is the earliest known recording of Manualism, that is, the art of playing music by squeezing air through the hands. By all accounts, that makes Cecil the first “Manualist,” although I suspect this musical style has a long and varied history, as least as old as clapping.

The last of Cecil’s life was plagued with health problems. The Traverse City Record-Eagle reported of his ill-health several times. On Tuesday, October 10, 1961, Cecil, living at 229 Wellington, was admitted to Munson. He had been dining at Bill Thomas’ Restaurant at 130 Park Street, when he fell ill. A “resuscitator unit” from the fire department was called to his aid, and the newspaper report stated he “suffered from an apparent heart attack.” He suffered additional bouts of illness that required hospitalization in 1970 and 1973, but ultimately lived to the ripe age of 89.

Enjoy Cecil’s rendition of “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” and the story of his talent, made available by the Internet Archive. This video is in the Public Domain, meaning there are no copyright restrictions, so please share out.

Amy Barritt is co-editor of Grand Traverse Journal.

By Robert D. Wilhelm

Edited by Julie Schopieray and Richard Fidler

[Editors note: This is a transcription of a manuscript Bob Wilhelm wrote over a long period of time, with updates ending in 1986. Some spelling and punctuation has been changed, and transcriber’s notes for clarity are in brackets]

A Note by historian Al Barnes

Doing the Impossible

I would have said it couldn’t be done. When Bob Wilhelm told me that he was going to do the history of the Wilhelm family of Traverse City I gave encouragement. However, tracing the family from their roots in Bohemia, before the turn of the century, to the “new world” and thence onward in time to the present day, was a task for a research group and not for one person.

From time to time he contacted me and we discussed many problems. Months turned into years and he persisted. He discovered the power of determination born in the pioneer family. He reflected this determination as page after page of the story unfolded.

Completed, the manuscript is fascinating and inspiring. I am positive that no stone was left unturned and no name left out of the story if that name left an echo at any point in the story of the Wilhelm family. I would not have had the patience.

CHAPTER 1: Conflagration in Bohemia

Central Europe in the mid-1800s was in turmoil. Count Clemens von Metternich, alter ego of the emperor of Austria and the Hapsburg dynasty, was not willing to let the demands for reforms sweeping through Europe spread into the Austrian Empire.

There were several reasons leading to the wave of dissatisfaction. Because of the Industrial Revolution, massive numbers of country people flocked to the cities hoping to improve their living conditions. Disillusionment soon swept through the masses. Unemployment, unequal distribution of wealth, slums, and unhappiness with an absolute monarch led to widespread disorders.

The government moved with brutal efficiency to quell the rising unrest. The military and the secret police were used to stamp out opposition. To keep the military ranks full, all young men were required to serve seven years at virtually no pay. The future held little more than becoming “cannon fodder.”

The Hapsburgs in their many wars with other European monarchs, needed young men. Country peasant stock was in the front lines. The attitude was “Why waste your best trained soldiers?”

In Bohemia, during the 1848-1850 period, the pan Slavic desire for Slavic unity and independence was proclaimed by Bohemian leadership. Meetings for unity and independence were held in Prague, but the speeches by the leaders resulted in confusion due to different languages.

Riots broke out in Prague and the Princess Windisch Gratz, wife of the governor, was killed by a stray bullet.

The Austrian cannons destroyed the patriotic hopes by the bombarding of Prague. The Bohemians were not able to withstand the armies of the Hapsburg monarchy. The bombardment was the beginning of the end for the independence movement. The Austrian army remained faithful, and a new period of desperation descended. It was so harsh that it made many yearn for the unhappy days under Metternich.

CHAPTER 2: Ondrejov to “Cincinnati”

It was during the summer of 1853 that a pamphlet describing the wonders of Cincinnati, Ohio, was circulated by a land agent in the village of Ondrejov, Bohemia.

Eva Wilhelm could not resist glowing reports of the mysterious land across the ocean. She started talking and tried to persuade her husband Joseph, a prosperous shopkeeper, to make the journey. Her pleading was rejected, but her brother-in-law and his wife, John and Mary Wilhelm, who lived in the nearby village of Cerna Buda, decided to go to America.

John Wilhelm was a tailor, but at the time he was dyeing and printing cotton fabrics. He was making a comfortable living for his family, but the future of his occupation was bleak. The talk of the area was Cincinnati, Ohio and its opportunities. While others could not make up their minds, John sold his interests and the family left on October 23, 1853. They reached New York in December.

Mary and two of their four sons were ill when they landed. They were admitted to the Marine Hospital in New York where one of them, Frank, died the next day. The second ailing son, Anton, died about a year later. The other children, Emanuel (age 13) and John (7 1/2) were temporarily placed in a children’s home until their father could get a job, their mother would be released from the hospital, and a boarding place could be found.

Braiding on garments was fashionable at the time. Being skilled in the art and able to speak German in addition to Bohemian, John was hired by a German tailor. When his wife recovered from her illness, the tailor offered her a job. John was curious about how the tailor knew she was a seamstress. The tailor explained he had noticed the neat patches on his shirt.

Emanuel, son of John and Mary, began working in a map making business during the day and attended school at night learning English.

CHAPTER 3: Mass exodus: Ondrejov to New York

Despite word of tragedy and hardships in New York, Eva Wilhelm was constantly urging her family and friends to leave Ondrejov. By the fall of 1854 her persuasiveness overcame the apprehensions. The exodus began.

Joseph Wilhelm and his wife Eva; his brother Anton, Joseph Kyselka, Wencil Bartak, Albert Novotny, Frank Kratochvil, Frank Lada, Joseph Knizek and Frank Pohoral, all with their wives and children, the mother of Joseph and Anton Wilhelm, and Pohoral’s unmarried sister were part of a group that finally settled in the Grand Traverse region.

Not all of the larger group settled in Michigan. Some migrated to Wisconsin. A cousin of Frank Kratochvil began the settlement of New Bohemia on Long Island, New York.

Even though Cincinnati was originally on the minds of the hundred migrants, not one settled there.

Unlike so many of the central Europeans who were totally destitute, this group, though lacking wealth, was nowhere close to being paupers. All of these families had the necessities of life even under the adverse conditions affecting Bohemia. They all had common school education. Anton Wilhelm’s wife Jennie was a teacher. She insisted that her family speak English, the language of their adopted land. Even though her children could speak Bohemian in later life, they were one of the few who could speak English without an accent. The men had all learned a trade while the women were all skilled in some form of needlework.

It was a three day journey from Ondrejov to the German seaport city of Bremen. A week’s search to find a sailing vessel resulted in the group boarding the Herzogen Von Alderberg.

There were steam vessels available for the journey, but a letter from John Wilhelm warned about the dangers of the steamers because one had blown up in the New York area. The boat carried 120 passengers, mostly Czechs (Bohemians), including a Czech band whose music helped break the tedium of the long journey There were also eighteen unmarried Germans and an English family named Williams on the consist. Each of the families was expected to furnish his own bedding, and their ticks (a cloth case for a mattress or pillow was rather coarse flax grown on the farms, spun by the women and woven by the town weaver).

One of the Czechs had a feather bed, part of a bride’s dowry, made of goose feathers. This was stolen and resulted in great discomfort in the winter weather. In addition to the warmth provided, these feather beds could be used as collateral for a loan.

The first meal served aboard was smoked, salty fish. Because the supply of water was limited, the passengers suffered greatly. Seasickness was another frequent misery. Some of the passengers brought dried fruits, mainly pears and prunes. Ondrejov had a community drying house where they could bring their crops for a small fee.

The voyage lasted longer than scheduled, seven-and-a-half weeks. Food and water supplies ran low. A.J Wilhelm in later years recalled that the basic diet at the end of the journey was black bread.

Because of the suffering of the children, Frank Lada lowered a small container attached to a cord into the diminishing water supply to relieve the distress. If a crew member should have observed such a happening, Lada would have been punished for breaking the ship’s rules.

When the boat finally arrived in New York, a number of children had to be admitted to an immigrants hospital for treatment. Many were emaciated from the lack of proper food and other discomforts suffered on the voyage. Many children died soon after arrival at the hospital and many other sick children lived a little longer. The large hospital ward was filled with rows of cots occupied by sick children.

Mothers were not allowed to be with their children in the hospital. Elizabeth Bartak’s mother pleaded with the nurses, but her requests were denied. She offered to scrub floors, a nurse tiring of the pleading pointed to a large dog and threatened her with attack. One day she arrived with patterns of lace. Going through the motions of knitting, the nurse understood she would make her some if she was allowed to stay. The offer was accepted.

A constant terror faced by the unsuspecting and trusting immigrants was the confidence men who preyed on all the newly arrived at the dock. As the Herzogen Von Alderberg tied up at the New York dock these people were only too helpful. Speaking their native language, a stranger offered to take them to a clean, moderately priced hotel, They trustingly and gratefully accepted. When the immigrants were presented with the bill, they realized they had been fleeced. A fist fight erupted. The hotelkeeper and his accomplices locked all the doors and the men were not to be released until they had given up all their worldly belongings. Fortunately, through the efforts of John Wilhelm and some of his friends he had made during his year in the United States, the situation was brought to the attention of the authorities and a refund of the overcharge was ordered. The court also ordered that these dishonest practices should cease. This satisfactory ending was rare. Most of the immigrants who were fleeced lost everything. Warning letters from the newly arrived to their family and friends back in Bohemia spread through the communities.

The carrying of money was especially dangerous. Unscrupulous passengers and crew members on the boats robbed the helpless. People waiting at the dock wanting to “help” the newly arrived disappeared as soon as they gained their worldly possessions.

Anna (Dufek) Brown was determined to make the journey to Leelanau County, Michigan. Her father, fearing the worst, wouldn’t allow his daughter to carry any money. All of her possessions were placed in a homemade trunk. Most of the space was for her featherbed. She wore a paisley shawl around her shoulders for warmth. She was presented with an amethyst or garnet necklace which was to be traded in for money when she reached New York. Arriving in New York, the immigrant agent ripped the necklace from her neck and put it in his pocket. His only comment was that people didn’t wear such necklaces in America.

The shopkeepers in New York used small coins to make change. Many could not get used to the American money and were easily confused. Another tactic of the unscrupulous was to give a handful of small change. The floors would be covered with sawdust so it would be difficult to recover your money. (This spreading of sawdust was done in the Grand Traverse region during the lumber era by some of the bar owners. Presumably drinkers would have a hard time finding change that had dropped to the floor).

Despite the problems of “strength makes right” hundreds of Bohemians from the area around Prague made the journey. Disease brought tragedy to many. Loss of all worldly goods by many slowed down the new life opportunities temporarily.

The exodus to the Great Lakes area was in full flight.

Look forward to the continuation of the History of the Wilhelm Family by Robert D. Wilhelm in upcoming issues of Grand Traverse Journal.