Newly acquired by the Kingsley Branch Library is an unpublished paper, “Early History of Kingsley and its People,” written for Creative Writing 203 (Instructor Dr. John Hepler) by Mable Henschell and Lena M. Snyder. This neat piece of scholarship earned its authors an A-, but we readers are awarded much more than that.

The authors interviewed second generation Kingsley residents, all children of the pioneer generation that settled in the valley that modern Kingsley now lies: Mable C. Snyder, Howard Dunn, George Fewless, Dr. J.J. Brownson, to name a few. From the ages given of those interviewed, and by doing a bit of genealogy detective work, the paper was likely written in 1947, about 80 years after the first lone men settled in what is now Paradise Township.

When reading this, think about several factors that color the description of the settlement of Kingsley. First, the authors were perhaps taking their interviewees at face value, despite the fact they were a generation removed from events. Second, the authors interviewed only those that stayed; One wonders if the families who abandoned their homesteads here would speak as passionately on the beauty of the valley. Third, the authors are both women attending college during the war years (As a complete aside, but nonetheless thought-provoking, Lena was about 40 years old, and was already employed as a teacher at Kingsley Schools, which raises a myriad of questions about her experience and motivations). One would imagine the wartime fervor for all things America found its way into this description as well, evidenced by the blatant admiration for the pioneers and their undoubtedly intrepid spirits.

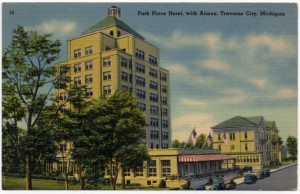

In this excerpt, Judson Kingsley (the man for whom the Village is named after), has packed his family up, presumably from somewhere in Illinois, and took a boat to Traverse City, following the Lake Michigan shoreline:

“Most of the families stopped in Traverse City for a few weeks (after disembarking at the harbor in Traverse City) before starting out to find their new homes, but Judson Kingsley decided to start out with his family and find a place he could call his own. He bought some food and hired a man to take him over the old state road to Grawn and then to Monroe Center. They saw some men working on the road as they rode along. Judson Kingsley asked the driver about the road, and he told them that in 1857, the legislature had passed an act authorizing the construction of the state road. It was to be called the Muskegon, Grand Rapids and Northport Road. Later it was changed to Newaygo and Northport State Road (editor’s note: The highway is now M-37). There was not much done on this road before 1860, just three years before the Kingsleys came over it. People had to travel on foot all the way to Grand Rapids, before this time, as there were only Indian trails. There were hardly any houses in this vast wilderness, which was known as ‘the big woods’. These woods were full of wolves, and some had followed Mr. Hannah when he walked on snow shoes from Traverse City to Grand Rapids. As the driver finished his story, they drove into Monroe Center. From here it was necessary to travel on foot over the old trails, for there were no roads east or west of the old state road…

The children were getting tired as the sun began sinking behind the horizon in the west, and the little family stopped for the night. A crude shelter was made of pine boughs. The tired travelers, weary from their hard journey, were soon fast asleep in this vast wilderness in a new country. The moon rose high into the sky, lighting the land until it lay bathed in silver light, with only the sounds of the nightbirds and insects to disturb the quietness of the night.

Day broke over the topmost trees, and the silver mist of the early morning surrounded them on every side, as Judson Kingsley’s little band moved farther and farther away from civilization. The smoke from an open fire indicated some settler had come in before they did. Later they saw Mr. Deyoe, and Mr. G.G. Nickerson, who said they had come from Illinois in December 1862. This was a year before the Kingsleys came over the trail. They had come to homestead the land, and as far as they knew, they were the only settlers in this vast wilderness. Judson Kingsley decided to move still farther into the big timber. They walked on watching for a suitable spot for their new home. At last they reached the top of a high hill and looked down into the most beautiful valley they had ever seen. A stream like a silver ribbon, angled in and out among the vast expanse of green. The sight was grand because of distance, color and outline, yet peaceful and undisturbed by the white man. Judson Kingsley decided this beautiful valley, which seemed like a paradise to him, would be their new home.

The Kingsleys were the first to homestead in the valley. Their claim was located where the present village of Kingsley now stands. They worked from early morning until late at night, and the woods resounded with the sturdy stroke of the woodsman’s ax, as they chopped the logs for their new home.”

There is so much here to research and verify, but for now, we will let Henschell and Snyder’s work stand alone, as a history captured in its time, through resources no longer available to our generation. Our thanks to them, as well as the donor, who had the foresight to offer this fine paper for preservation. You are welcome to review the work in its entirety at the Kingsley Branch Library.