Editor’s Note: This text comes to us courtesy of the July 1953 issue of Railroad Magazine, and republished with permission from Mr. EuDaly of White River Productions. A copy was recently donated to the Local History Collection by Mr. Allan Pratt. This particular article will be of interest to railroad historians of Northern Michigan, but also to those who hike or camp in the area, as many of former lumber pikes have, over time, become part of our trails. This article also answers a number of questions brought in by the curious.

by Fred C. Olds

The racing crests of Michigan’s big rivers, with picturesque river hogs riding spring log drives, captured most of the glamour in Michigan’s lumbering history. All but forgotten, less colorful but just as vital to the timber industry, was the role played by the logging railroad. Pushing out into isolated forest cuttings, these little iron pikes early in the 20th Century criss-crossed the northern and central interior of lower Michigan in a web-like pattern of rail.

Their existence dependent upon the product they transported, most were doomed from the start for but a brief span of operation. Mileage grew at a furious pace as rails opened new timber areas for the lumberjack harvest, but these little pikes withered almost as quickly on their iron vines when the logs were cut off. Their demise was often sudden and without ceremony. Abandonment of a forest road simply meant piling its equipment, including locomotives, on flatcars to be carried out over its own creaky rails for service in another sector or for another owner.

How and where did the logging railroad get its start in Michigan?

Records show that by 1875 loggers had been busily chewing into the state’s extensive forests for over 40 years. Over this period commercial lumbering interests had steadily whittled their way northward, skirting the shores of Lake Huron and Michigan, penetrating inland along the larger rivers — the Grand, Tittabawasee, Saginaw, Au Sable, Muskegon, Manistee, Chippewa, Pere Marquette and their tributary streams – to strip out the lush stands of cork pine. In those first years water played the major role as a log hauler. Timber (pine, that is) had to be readily accessible to a suitable stream for flotage or it was practically valueless. It was this lack of water transportation, according to a claim set forth in an old issue of The Northwestern Lumberman that caused the nation’s first logging railroad to be built in Michigan’s Clare County in 1876. Its builder was Winfield Scott Gerrish, who owned extensive pine holdings in Clare in the center of Michigan’s lower peninsula about halfway between the Straits of Mackinac and the Ohio line.

A brief biography of Gerrish, carried in A History of Northern Michigan, shows that he gave early promise as a timber operator. Born in Maine, where his father Nathaniel was a lumberman, young Gerrish spent his boyhood and early manhood in Croton, Michigan; started driving logs at the age of 18, and when 25 made his first large logging contract. It called for the timber to be beanked on Doc & Tom Creek in the southwest part of Clare County in 1874 for flotage to mills in Muskegon via the Muskegon River. Misfortune struck without warning, however. The Doc & Tom shrank to a mere rivulet as the result of a spring drought, and Gerrish’s winter cut of logs was left high and dry on the banks.

Gerrish managed to float his cargo to mill by dint of hard work, but he conceded that small streams proved an unsure means of transporting his timber. He obtained an interest in 12,000 acres of pine on the west side of Clare County between the headwaters of the Muskegon River and Lake George, but because of its remoteness (6 to 10 miles) from a good floating stream, not a tree had been cut in this tract Gerrish was not one to be easily discouraged. The Northwestern Lumberman report noted that he considered pole roads and tramways to transport logs but tried neither method, believing both were impractical. Instead, he found his solution in a most unlikely spot — hundred of miles away, at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. While on a visit there he saw a small Baldwin-built locomotive displayed in a machinery exhibit. It gave him an idea.

If he couldn’t gloat his logs to the Muskegon River, why not haul them on the first leg of their journey by rail? Figuring that it was worth a try, he hurried home and hastily built the Lake George and Muskegon River Railroad, as he called it, which was splashing its valuable timber merchandise into the mighty Muskegon early in 1876. The Northwestern Lumberman account calls this 6-mile pike, running from Lake George northwesterly to the river near the present village of Temple, the nation’s and perhaps the world’s first logging railroad. Other railroads had penetrated timber areas before that time but conducted a general greight and passenger business. The LG&MR was strictly a log hauler, and as such is claimed to have been the first of its kind.

Gerrish, Edmund Hazelton and four associates of Hersey, Michigan, were listed as the road’s incorporators in a Special Report of the Michigan Railroad COmmission. on November 28th, 1881 the railroad was acquired by John L. Woods and on February 18th, 1882 by C.H. Hackley & Co., the last named a large Muskegon firm which operated it as a forest road until its sale in the Toledo, Ann Arbor & Cadillac Railway (now part of the Ann Arbor Railroad) between August 25th and December 20th, 1886. Approximately four miles of the old LG&MR grade now carry Ann Arbor rails between Lake George and Temple.

It’s very lonesome country up there, particularly in the winter months. Acres of stumps scar its ridges and valleys, a fading legacy from that long-lost pine kingdom. Paralleling Highway 10 west from Clare for a few miles, the Ann Arbor rails turn northwest to skirt Lake George along its east rim, cutting a thin swath through the brushy second-growth timber and yopung sprice as it heads toward Temple, Casillac and its Lake Michigan terminus at Elberta. Lake George is a bustling resort community in the summer, but the old gray depot has been closed for many years.

Gerrish, after completing his logging short line, espanded his lumbering operations until his biographer described himas being at one time probably the world’s largest indicidual logger. It is estimated that his highest individual contribution to the Muskegon River was 130,000,000 feet of timber in 1879. Most of this was carried over his Lake George & Muskegon River Railroad — not a bad tonnage record for a little two-bit logging pike founded only three years before.

His new transportation idea gained quick favor among the state’s lumber kings. It ushered in a new era, opening up hitherto unprofitable but heavily timbered pine and hardwood country. It brought an unprecedented boom in Michigan railroad building. Both broad and narrow-gauge lines were pushed deeper into backwoods districts to take out timber. For a few years a weird assortment of motive power echoed their whistle tones across the long plains and forested hills. Saddle-tank dinkeys and Shay-geared sidewinders chuffed and clanked over hastily-built rails which meandered around hills and across swamps, their tenders and log cars bearing now all but forgotten titles.

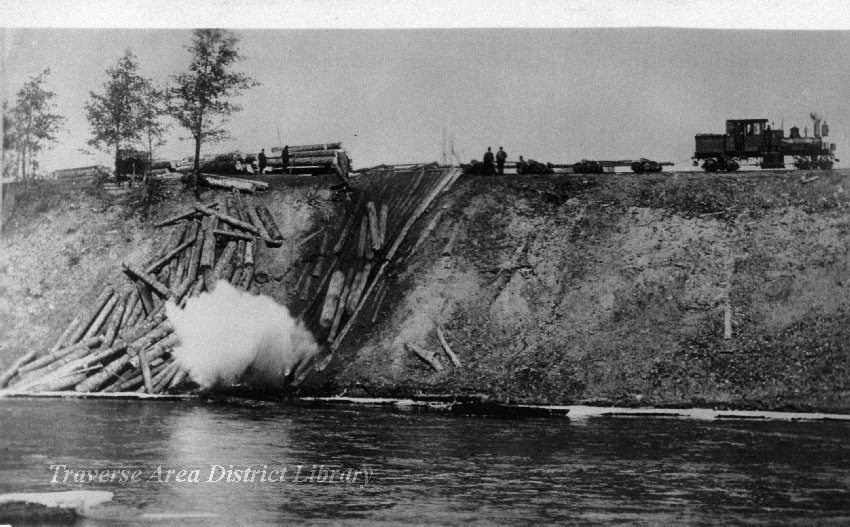

Built for a special purpose , log hauling, these railroads accomplished their chore efficiently and without delays. A venture as utilitarian as the lumbermen’s favorite axiom, “Cut and get out,” no money was wasted on frills, deluxe equipment, or polished roadbed. Swampers would first slash a rough path cross-country from an owner’s timber tract to the nearest river if his logs were to be floated part of their journey by stream, or directly to his own mill, or to a rail junction where they could be transferred to an already established carrier to complete their trip.

Rails followed a path of least resistance, guided by the hastily scraped-up roadbed’s serpentine twisting and turning to take advantage of the land’s natural contours. Hills and extensive swamps were skirted when possible, to avoid expensive fills and steep grades. To cross a swamp, low log trestles were built to provide the track with a solid bottom instead of using earth fill, timber being cheaper than the cost of moving dirt. Many of Michigan’s vacationland hunting and fishing trails still in use today were built over all or part of some timber rail line.

Motive power, based upon modern standards, would be considered mediocre. Locomotives during the early period wore bonnet stacks, burned slab wood for fuel, moved after dark to the feeble rays cast by oil headlamps, and hauled primitive four-wheel flatcars whose link-and-pin couplers exposed trainmen to an extra hazard. Lightweight rail, sometimes strap iron screwed to a wood base and set insecurely upon the rough roadbed, made the journey into the woods comparable to a sea voyage.

Back in the forests the trees were chopped down, trimmed of their branches and their trunks cut into suitable lengths. A log then was skidded through the brush by a team of horses or oxen to an opening where a set of big wheels could be driven over it. The log (two or three logs if they were small) would then be lifted and carried to a rail-side decking ground where a jamming crew loaded the log lengths on railroad cars. In winter the big wheels were supplanted by sleighs which carried the big piles of logs to the decking ground.

Loading cars of logs was described by Ferris E. Lewis in the December 1948 issue of Michigan History: “Short wooden pins were first driven into iron brackets on the side of the flatcars to keep the logs from falling off. Hooks like ice tongs, each one at the end of a steel cable, were placed in the ends of a log. A little team of horses with muscles as hard as knots, at the command of a teamster who drove them without reins, would raise the log and swing it over the flatcar where it would be lowered gently into place. One by one the logs were loaded onto a car. A pyramid pile, placed lengthwise of the car, was thus built at each end. When a car was loaded, it would be moved away and a new one would take its place.

In later years steam jammers replaced horse power, particularly among the larger operators. These were the conditions and equipment used along one of the nation’s last frontiers to attack the final great stand of pine and hardwood timber remaining in Michigan as the 19th Century came to a close.

Besides increasing production, these railroads revolutionized the industry by making logging a year-round business. Owners found they no longer were dependent upon proper river levels for their log transportation, and cutting could continue around the calendar instead of just during the winter months. Some figures proving this accomplishment are cited in the book, Lumber and Forestry Industry of the Northwest, for just three railroads — the Grand Rapids & Indiana, Flint & Pere Marquette, and Manistee & Grand Rapids. Each of the these [sic] conducted a general freight and passenger business, although primarily engaged in timber hauling during the years cited.

Mills along the Grand Rapids & Indiana (now part of the Pennsylvania Railroad) manufactured 367,000,000 feet of lumber and 404,000,000 shingles in 1886, while the total output along this road, from construction of the first mill in 1865, to 1898, is estimated at 6,000,000,000 feet of lumber. Timber production on the old Flint & Pere Marquette (now part of the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway) totaled 5,000,000,000 feet between 1876 and 1896. The Manistee & Grand Rapids (later named the Michigan East & West and eventually abandoned) placed 500,000,000 feet of pine and 1,000,000,000 feet of hardwood timber into Manistee sawmills for cutting in 1891. In the Cadillac region up near Grand Traverse Bay on Lake Michigan, it was not uncommon for a pine tree to yield three logs, each of which would reach across car sills set 30 to 33 feet apart.

Another distinction claimed by the Cadillac region in logging transportation was the invention there of the narrow-gage [sic} Shay logging locomotive in 1873 and 1874 by Ephraim Shay. Slow but powerful, the Shay-engine had vertical pistons to operate the driving cranks, working a shaft geered [sic] to the motive wheels.

An account carried in The Cadillac Evening News said that Shay developed his locomotive to pull log cars from northwest of Cadillac to his sawmill at Haring. First made in Cadillac, its patents were later sold to the Lima Machine Works in Ohio, which manufactured it for use all over the world.

There is not a logging railroad, operating as such, remaining in the lower peninsula. In fact, their names even escape the memory of all but old timers. Mention the Lake Count Railroad and among railroaders you would likely draw only blank looks. Or the Cadillac & Northeastern, Louis Sands’ Road, Nesson Lumber Company, Cody & Moore, Bear Lake & Eastern, or the Canfield Road — recalling only a few.

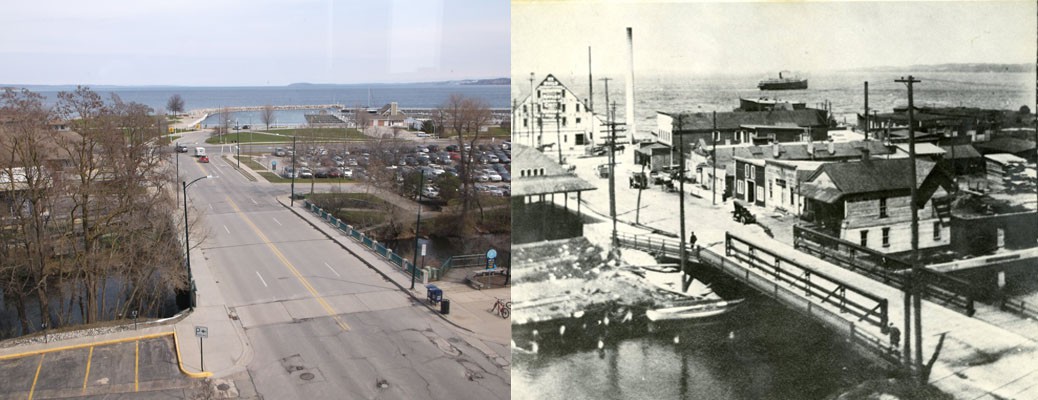

The logging railroad gave rise to few legends. It could not match the glamour attached to sawmill towns which grew and flourished beside its tracks, nor could it furnish the rough color provided by the swift rivers with their tension-packed spring drives. Its mark upon the timber country, once painted briefly in bold outline, today has virtually disappeared. Traces, of course, can still be found in the old crumbling grades winding unevenly across grassy plains and ridges, pointing toward some distant banking ground. The old names, with some searching, can be found buried in official reports listing rail mergers and abandonments. But that about ends it. That and some faded photos, dim with age, gathering dust in old picture albums.

Editor’s Note: A more recent article on the subject, authored by Carl Jay Bajema, was published in the April 1991 issue of Forest & Conservation History, Vol. 35, No. 2 (Apr., 1991), pp. 76-83. “The First Logging Railroads in the Great Lakes Region” is available online, made available by Grand Valley State University: http://www.gvsu.edu/anthropology/adc/files/document/1DB0E4E0-DCDC-7956-473CC7989F113C65.pdf