We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us. -Winston Churchill

Renovation and repurposing are popular. Proud do-it-yourself folk will be glad to show you the end tables they salvaged to make a bench, or gloat over their latest acquisition from Odom’s (a wonderful reusable building materials supply store in Grawn). We have all sorts of fun jargon to describe these activities: recycling, upcycling, flea market treasure-hunting. Demolition is violent and ugly, whereas reusing materials makes us proud, like the craftsmen of old who hewed their mortise-and-tenon joints one at a time.

The most ambitious of these projects must be the restoration of an entire building. The end of some buildings, like those recently demolished in Traverse City’s warehouse district, (where concrete block won out over fine architecture) tends not to pull at the heart strings. But in many cases the intrinsic value of a building merits the effort of removal and renovation.

Even if you can reuse a building on a different site, how do you move it safely? In the modern era with equipment and wide-load trucks (a ubiquitous sight when you are needing to get somewhere quickly and are headed down a narrow road with no shoulders), the task is more than possible. But let’s take a look at “then,” when horsepower wasn’t just an abstract unit of measure.

The original structure for Grace Episcopal Church was built on property donated by Hannah, Lay & Company, located in Traverse City on State Street between Cass and Union; dedication took place November 12th, 1876.

After construction, the church enjoyed a thriving congregation due to the draw of well-esteemed clergymen, from 1876 to 1886. In that last year, Rev. Joseph S. Large vacated his office due to ill-health and the church found its congregation numbers in a slump, forcing the doors closed until 1891. A new call was put out that year, and the church building was again put to use.

For reasons not clear now, the location of the building was a problem, but the members deemed the building’s sacred purpose warranted the effort of preservation. In stepped James Morgan, a Chicago businessman and partner in Hannah, Lay & Company, who encouraged the removal of the building to it’s current location at 341 Washington, across the street from the County Courthouse.

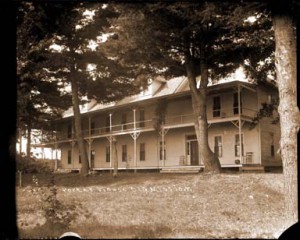

By employing jacks, the church was first lifted off its foundation; heavy beams, greased and with pointed ends, were secured to the underside, which would act like runners on a sled. A temporary wooden track made of flat planks and cross ties (similar to railroad tracks) were laid on the roadway, and the structure was pulled across the track on the greased beams. Once part of the track was cleared, workers would move and install the track at the front of the structure, and the job continued.

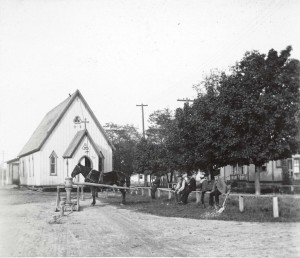

A capstan was necessary to apply enough force to move the church, as a lone horse wouldn’t be strong enough on its own. This capstan operated much like the ones seen on ships to raise anchor. In the photograph, you can see the capstan was moored in the roadway with large posts driven into the ground and attached with chains. The horse would rotate the axle by walking in a circle and would pull the structure along the temporary track. As the picture was taken while the horse was resting, the chains mooring the capstan to the ground are slack.

Wondering how much the Church was set back for this endeavor? We are led to believe that Mr. Morgan footed the bill, at a cost of “nearly one-thousand dollars,” or about $30,000 by today’s dollar value.

Ann Hackett, Parish Administrator of the modern Grace Episcopal Church, gave me a tour of the interior of the remodeled church. As she explained, when it became clear that the previous structure was no longer viable, the congregation made every effort to retain the overall feel of the church by focusing on the details.

The stained glass windows were salvaged and used in the new structure, as was the original altar and painted archway. The cornices in the modern building were modeled after the original fixtures, and the interior was surfaced in wood bead board, mimicking the interior of the original.

The new baptismal font, which is situated immediately within the Church’s nave, best illustrates the congregation’s drive for authenticity. The original font was too small to meet the purpose of the growing Church; craftsmen created the new font to have a similar overall shape and use the same font-letter style, as shown here. Grace Episcopal Church is a perfect example of the beauty and pride we share when we salvage the past.

References

Leach, M.L. “A History of the Grand Traverse Region,” 1883.

Sprague, Elwin. “Sprague’s History of Grand Traverse and Leelanaw Counties, Michigan,” 1903.

“The Value of a Dollar, 1860-2014,” fifth edition.

Thanks to www.shiawaseehistory.com for their description of house moving in the turn of the last century.

Thanks to the Binkley’s for allowing use of their house moving photograph through a Creative Commons license: https://www.flickr.com/photos/binkley27/.

Thanks to Ann Hackett, Parish Administrator, and her staff for their time.

Amy Barritt is a librarian at Traverse Area District Library and co-editor of Grand Traverse Journal. She enjoys going out and discovering history, especially when she makes new friends at the same time!