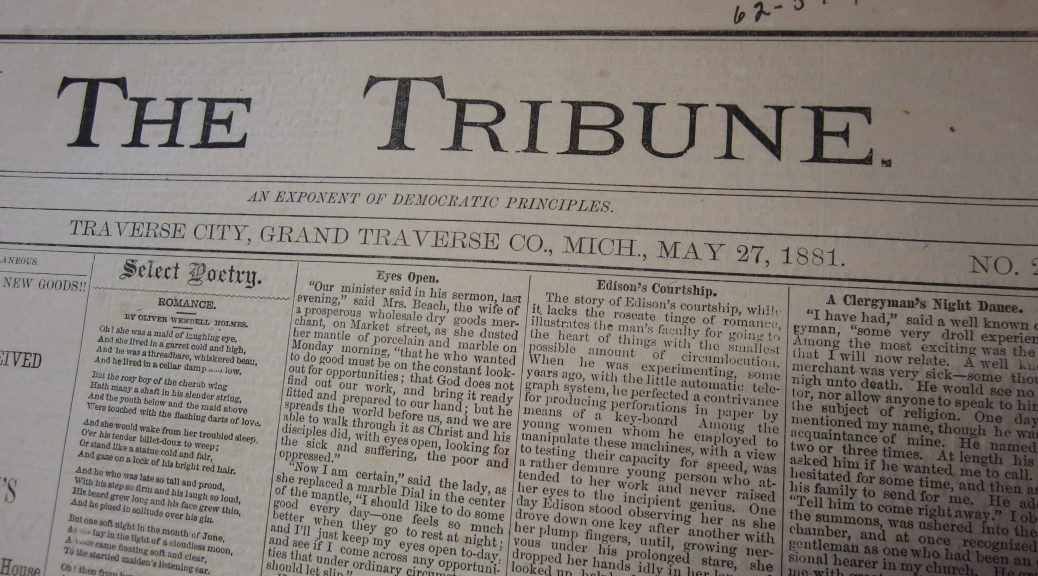

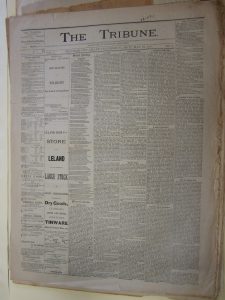

Recently uncovered in our local history files here at Traverse Area District Library were three photographs and a handful of typed memos, that tell the story of the end of the Campbell House. You may know it better as the Park Place Hotel, the name Perry Hannah and A. Tracy Lay graced the building with after they purchased the property in 1878.

Recently uncovered in our local history files here at Traverse Area District Library were three photographs and a handful of typed memos, that tell the story of the end of the Campbell House. You may know it better as the Park Place Hotel, the name Perry Hannah and A. Tracy Lay graced the building with after they purchased the property in 1878.

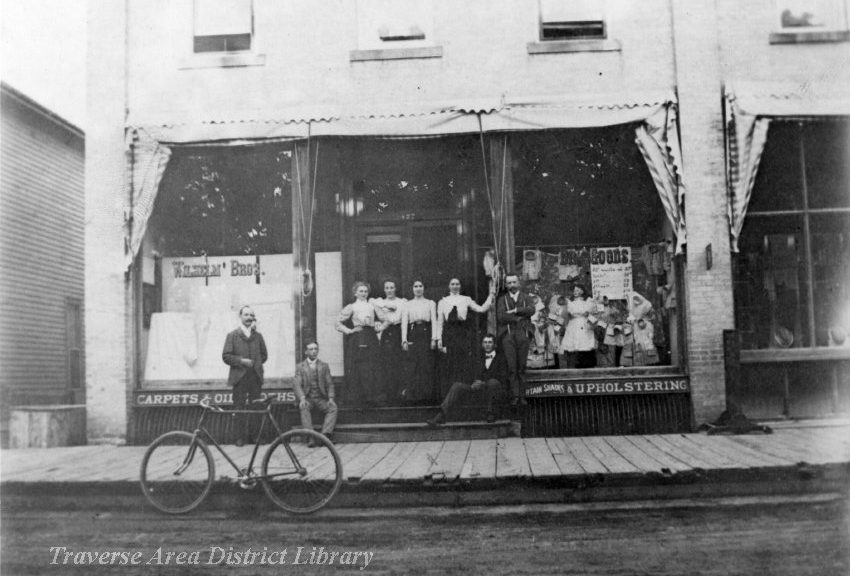

The Campbell House was announced as open for business in the Grand Traverse Herald on November 20, 1873, by proprietor Henry D. Campbell. The imposing three-story wooden structure dwarfed most of the surrounding buildings. You might be surprised to hear that the House sat at the southeast corner of State and Park Streets, “fronting State Street on the north and Park Place on the west,” 80 feet by 82 feet respectively. How is that possible? Before the Park Place was built at its current location, Park Street (or Park Place, the names were used interchangeably) extended through to Washington Street.

The Campbell House was announced as open for business in the Grand Traverse Herald on November 20, 1873, by proprietor Henry D. Campbell. The imposing three-story wooden structure dwarfed most of the surrounding buildings. You might be surprised to hear that the House sat at the southeast corner of State and Park Streets, “fronting State Street on the north and Park Place on the west,” 80 feet by 82 feet respectively. How is that possible? Before the Park Place was built at its current location, Park Street (or Park Place, the names were used interchangeably) extended through to Washington Street.

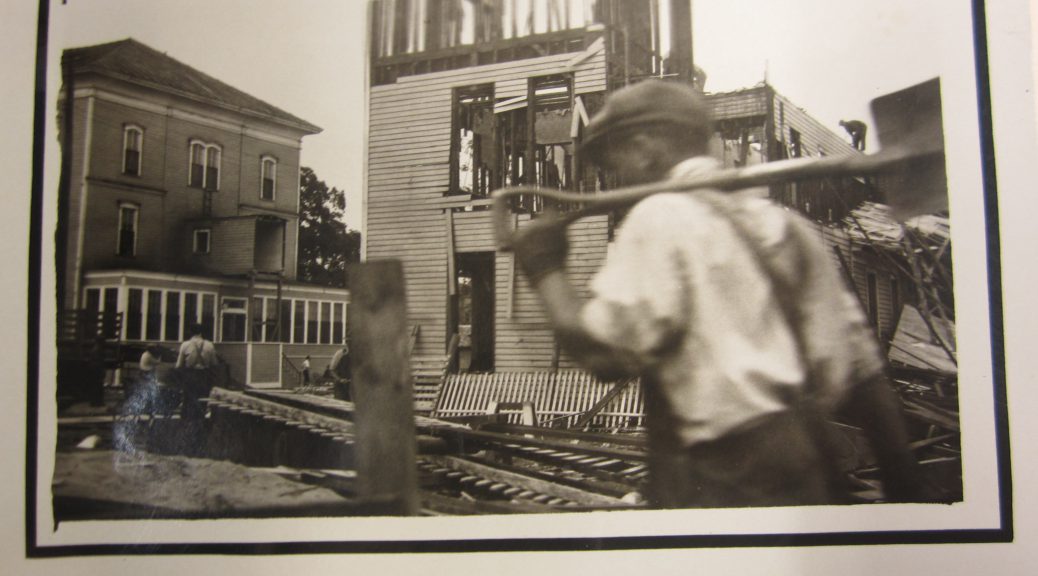

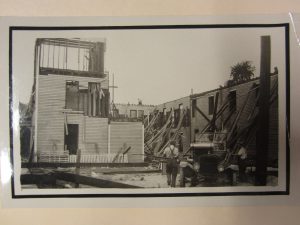

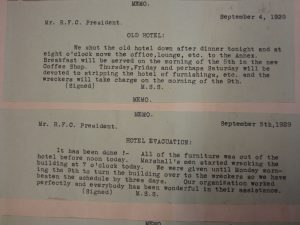

The all-wooden structure “succeeded to progress of the age,” according to the Traverse City Record-Eagle, who reported on the the demise of the original building on September 6, 1929. By the memos found, we know that the Hotel staff, including a moving gang of 20 men, were able to remove all the furniture before noon on September 5th, beating the scheduled evacuation date of September 9th by three days. The wrecking crew wasted no time, and began demolition the same day (right about 7 p.m.) that the building was evacuated.

The all-wooden structure “succeeded to progress of the age,” according to the Traverse City Record-Eagle, who reported on the the demise of the original building on September 6, 1929. By the memos found, we know that the Hotel staff, including a moving gang of 20 men, were able to remove all the furniture before noon on September 5th, beating the scheduled evacuation date of September 9th by three days. The wrecking crew wasted no time, and began demolition the same day (right about 7 p.m.) that the building was evacuated.

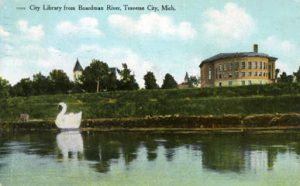

The Park Place Hotel as we know it, with its 1930s Art Deco construction, was finished and open for business in June 1930. In the meantime, business continued as usual for the staff. How was that possible? There was no building, right?

Few probably remember The Annex, which was located basically where the Park Place’s covered parking structure is today, and served as the “offsite location” of the Park Place Hotel. The Hannah & Lay Company originally constructed the Annex when business outgrew the original structure. When the portion of the building that was the Campbell House still stood, the two buildings were linked by an overhead, covered walkway that extended across Park Street. It operated as a complete hotel for guests, and was lightly remodeled to create additional space for an office, lounge, and a coffee shop and grill.

Few probably remember The Annex, which was located basically where the Park Place’s covered parking structure is today, and served as the “offsite location” of the Park Place Hotel. The Hannah & Lay Company originally constructed the Annex when business outgrew the original structure. When the portion of the building that was the Campbell House still stood, the two buildings were linked by an overhead, covered walkway that extended across Park Street. It operated as a complete hotel for guests, and was lightly remodeled to create additional space for an office, lounge, and a coffee shop and grill.

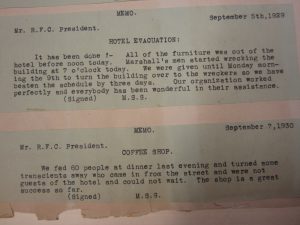

The Annex Coffee Shop was such a success that the Park Place continued to operate at that location for another year, even after the new Park Place Hotel building was finished. As the Park Place itself described the Annex, it was “very convenient for Luncheon when downtown or an afternoon game is on… Or perhaps Sunday dinner when you are dressed up and look so nice.” Classy!

The Annex Coffee Shop was such a success that the Park Place continued to operate at that location for another year, even after the new Park Place Hotel building was finished. As the Park Place itself described the Annex, it was “very convenient for Luncheon when downtown or an afternoon game is on… Or perhaps Sunday dinner when you are dressed up and look so nice.” Classy!

Amy Barritt is co-editor of Grand Traverse Journal, and special collections librarian at Traverse Area District Library. Thanks go to Marlas Hanson for re-discovering these gems on the Campbell House!