by Julie Schopieray

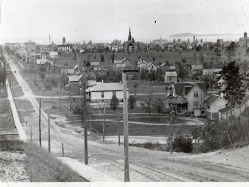

The recent demolition of a once lovely, large house on S. Union Street, kindled the desire to investigate the history of the home. Built before 1888, it was first the home of George E. Steele and located in the south side subdivision known as Fernwood.

In 1888, Steele sold it to real estate dealer Philip Lang. After Lang’s sudden death in 1890 (he shot himself in the basement of the home), his widow Anna married Dr. Julius K. Elms, a homeopathist and surgeon, who came to Traverse City in 1881 and practiced medicine in various villages in the Grand Traverse area. By the mid-1890s, Dr. Elms had a well established practice with an office on the upper floor of the Markham block at 129 E. Front St. A capable physician trained in Chicago, he successfully tended to the needs of the community, but, by 1898, was struggling to make ends meet, having made a risky investment which may have doomed his career in Traverse City.

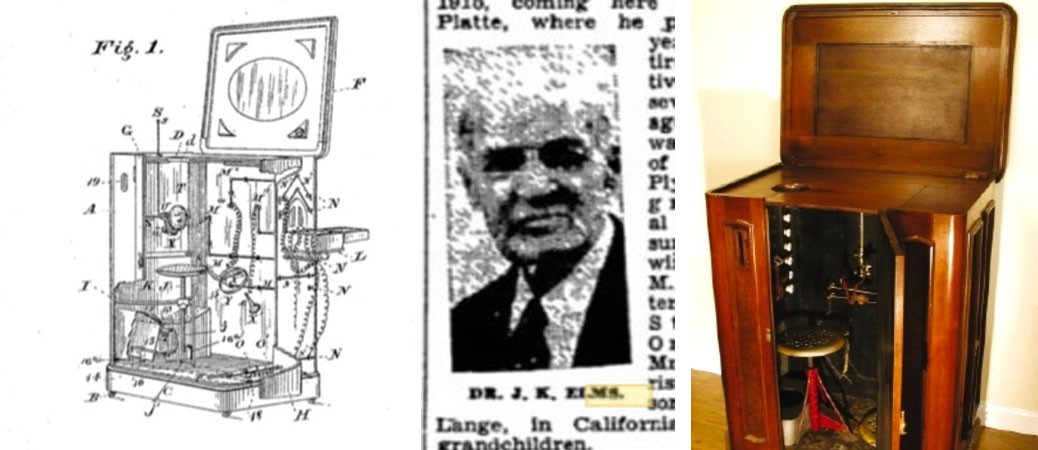

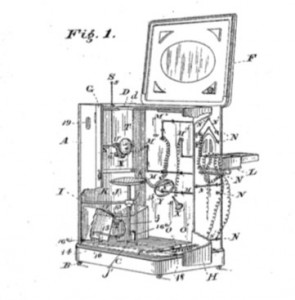

On February 8, 1898, Dr. Ludwig Von Dolcke and his female assistant, Miss Hattie V. Hadley, arrived at the Park Place hotel. The doctor immediately began to run ads in the local paper, obviously written by himself, carefully worded to lure curious and desperate patients to try his treatments. “Dr. Ludwig von Dolcke, the eminent inventor of the electro-theropeutic cabinet bath, and who is termed “nature’s doctor,” is …in the city and he will be pleased to give free consultation to a limited number during the remainder of his stay at the Park Place which will not be long….” Von Dolcke had patented his version of an electric bath cabinet in 1884.

These devices were first invented in the mid-1870s, so Von Dolcke was not the first to patent one- his was an “improved version.” It was basically a large lidded wooden box with a stool and wiring connected to “electrode sponges” which were placed on the part of the body to be treated. Powered by a battery, a patient could be given various levels of electric current from mild, to as strong as desired. Holes in the cabinet allowed for employing vapor ( Russian bath) or hot air (Turkish bath) depending on the type of bath requested. The treatments were said to increase circulation, help symptoms of Brights Disease, rheumatism, dropsy, eczema and other skin affections, gout and many other maladies.

These devices were first invented in the mid-1870s, so Von Dolcke was not the first to patent one- his was an “improved version.” It was basically a large lidded wooden box with a stool and wiring connected to “electrode sponges” which were placed on the part of the body to be treated. Powered by a battery, a patient could be given various levels of electric current from mild, to as strong as desired. Holes in the cabinet allowed for employing vapor ( Russian bath) or hot air (Turkish bath) depending on the type of bath requested. The treatments were said to increase circulation, help symptoms of Brights Disease, rheumatism, dropsy, eczema and other skin affections, gout and many other maladies.

Dr. Von Dolcke’s presence in Traverse City seems to have stirred some suspicion, however. Local physician Dr. H.B. Garner had likely heard of his reputation, and questioned whether Von Dolcke had registered to practice medicine during his electric bath sessions in town. Von Dolcke was charged five dollars for violating the state law, and did register a couple weeks after arriving, claiming ignorance about having to register to practice medicine in the county.

For nearly fifteen years Von Dolcke had traveled the Midwest selling his inventions to small town doctors. A flamboyant character often seen wearing odd costumes, his credentials were sketchy at best–one article stated his medical training was earned at the University of Iceland, and another said it was in Sweden. After inventing his first electric therapy bath in 1884, he opened the Electro-Hygenic Institute in Cincinnati where he trained people (usually women) to use the devices, sending them out to sell them across the country.

He had gained a reputation across the country for making wild medical claims. He charged outrageous amounts for his electric bath cabinets, and was sued numerous times for various reasons–including practicing medicine without a license, refusing to testify in court about the death of a young woman after a botched abortion, and in 1891, inventing a scheme (which was widely covered in papers across the country) to move the entire population of Iceland (the place he proclaimed to be his homeland) to Alaska where he claimed to be working with capitalists.

Dr. Von Dolcke stated he’d traveled the world and even treated Queen Victoria and other European notables, bragging that he, himself, was a descendant of Danish nobility. In fact, no trace of the man’s heritage can be documented, nor his existence under that name before 1882. Unbelievably, in one interview he claimed he’d come to the country in 1844 as a “commissioner” to select the land in Dakota territory where a colony of 6,000 Icelanders would eventually settle. The problem with that claim is that he would have only been about two years old in 1844. His reputation was well known in Michigan since he had established practices in Grand Rapids and Detroit (and had been sued in both cities). It was no surprise that some people were wary of his intentions when he arrived in Traverse City.

The ads the Von Dolcke placed in the newspapers paper during his visit in 1898, made claims for all sorts of cures from his treatments, just as other “doctors” did with these machines since they first appeared about 1874. The most famous physician in Michigan during this time was Dr. John Kellogg of Battle Creek, whose successful sanitarium drew sufferers from all over the country. The notoriety of Kellogg, who also used a version of electric bath therapy, may have added to the surprising success of Dr. Von Dolcke’s invention. During their time in Traverse City, Von Dolcke’s female partner ran the treatments for women. Ads boasted of the success she was having with the ladies of Traverse City.

“Miss Hattie V. Hadley, came to this city a few weeks ago to introduce the bath which was entirely new to Traverse City people but it is already becoming widely known as those who first tried its health giving properties were so pleased with its success, that the good word had passed along until now Miss Hadley had nearly every hour taken with ladies seeking relief from ailments which have become chronic. Among her patients are ladies who have already experienced marvelous changes in their physical being and they cannot commend the method enough. [Traverse City Evening Record Feb. 13, 1898]

Dr. Elms seems to have been completely taken in by Von Dolcke’s free demonstrations and within a month, the paper announced that he had purchased the electric bath cabinet from Dr. Von Dolcke, who then left town as quickly as he had appeared. By April, Dr. Elms began to run ads of his own, describing the various kinds of therapies he was now offering.

Dr. J.K Elms has made complete arrangements in his rooms in the Markham block for treatment of patients with an electric bath cabinet. Men as well as women and children may have baths given them from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. Russian, Vapor, Turkish, Turko-Russian and medicated baths given to suit the patient. Mrs. Elms is in attendance and will care for ladies. The virtues of this electric method are wonderful and rheumatism and chronic diseases are banished through its influence. –Evening Record 9 April 1898.

Another article described each type of therapy offered by Dr. Elms, reassuring potential patients that each sex would be attended to by an attendant of the same gender “with the greatest possible delicacy.”

According to the Traverse Bay Eagle, Dr. Elms offered the electric bath, a Turko-Russian bath which was “equal degrees of dry hot air and pure warm vapor”, a Roman Bath “wherein the patient is exposed, first, to a gentle lubricating… warm vapor, then receives a sponge bath…followed by the stimulating and toning effect of the hot dry air bath and the various medications.” There were perfumed baths “wherein many different oils are used… oil of rose, jasmine…violets, mustard, cloves, cinnamon, etc.” There was a medicated Turkish bath “wherein the hot dry air is incorporated pregnated, charged or comingled with fumes of certain pure and specific medicinal agents, as salts, sulphur, tannin, etc., etc., which are burned, the fumes being absorbed through the pores of the skin while these are dilated by the hot air”. The Eagle cautioned readers that the baths are only administered upon the advice of and by prescription of a physician.

The Turkish bath had been practiced in the Middle East for hundreds of years and gained popularity in the West during the Victorian era. Many were established around Europe, but the kind offered in Dr. Elms’ office were obviously on a much smaller scale.

Dr. Elms’ electric bath therapy seems to have been short-lived in Traverse City. There is no mention of it after November 1898, but wouldn’t it be interesting to know how many Traverse City people tried the treatments?

Perhaps his somewhat controversial medical practices were the reason for his financial woes and frequent moves, documented in the city directories. By June 1898 he had closed his office in the Markham building and turned his Union St. home into a sanitarium, moving his electric and Turkish baths to this location, still offering the therapy sessions. In different years his offices were in Grawn and Monroe Center, but in 1900 he again returned to Traverse City and established an office in the new Wilhelm Block, on the NW corner of Front and Union Streets.

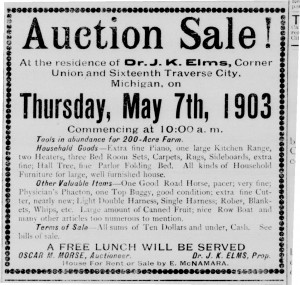

By May 1903, he had even more financial troubles. His property on S. Union and 16th was repossessed and went up for sale. By 1905, Elms had permanently left Traverse City. After that time, the house must have sat unused for a number of years. In 1910 it was rented by the county to use as a temporary poor house. A new facility was in the process of being built south of town (the Boardman Valley Hospital). The Elms property offered the ideal temporary location until the new one was finished. “This building will make the most excellent and comfortable quarters for the county’s poor, as the structure is fully equipped with electric lights and a furnace and has sufficient room to care for the inmates in a proper manner.” [ Traverse City Evening Record, 24 Oct. 1910]

After the new poor farm was completed, the Elms house was sold and once again used as a residence until it was torn down in early April 2015.

After the new poor farm was completed, the Elms house was sold and once again used as a residence until it was torn down in early April 2015.

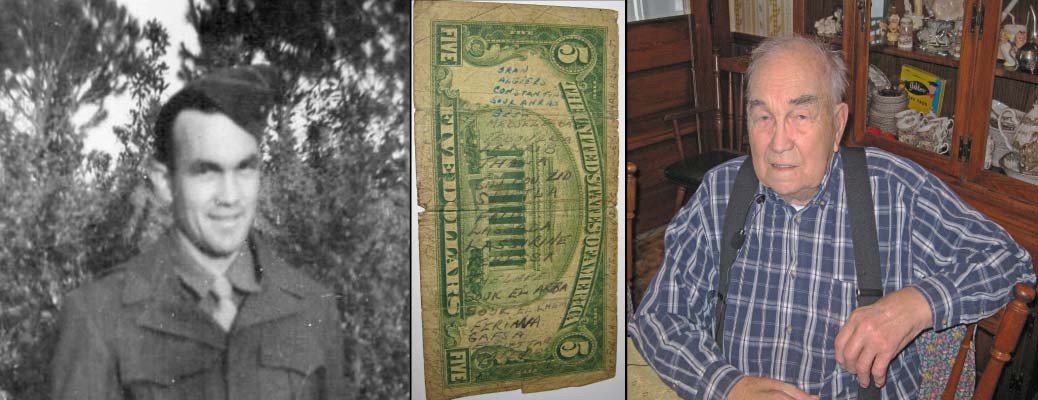

By 1907 had Dr. Elms had permanently settled in Nebraska near a brother who was also a physician, and continued his practice for another twenty years. He died in 1938 at the age of 90. His life was both long and colorful.

Who was Von Dolcke?

Dr. Von Dolcke married twice, once in Canada in August 1890, then to another woman in Detroit in June 1891. Each marriage certificate listed different parents’ names for Dr. Von Dolcke. What happened to the first wife is unclear. She seems to have returned to her maiden name after 1890, and lost custody of the son she had with her first husband. She had been running a boarding house in Grand Rapids (where Von Dolcke had lived) with her husband and son, prior to marrying the doctor.

The doctor had three children with his second wife, Rose. His first child’s name was entirely fitting– Electra, born in 1892, was an aspiring opera singer but without much success. She married twice and lived in Detroit. Another daughter, Ann, married and resided in Detroit as well. His son Arthur, born in 1893, married a northern Michigan woman whose parents owned the popular Beach Hotel in Charlevoix.

In 1929 Arthur sold to a New Orleans collector of antiquities, a cane he supposedly received from his father. “…S. J. Shwartz…purchased Lincoln’s cane recently from Arthur L. Von Dolcke, of Charlevoix, Mich. Dolcke had received it from his father, who in turn had got it from a Negro janitor of Ford’s theater. An affidavit accompanying the cane relates that the janitor found it in the theater box the night Lincoln was shot and had given it to Dr. von Dolcke of Washington.” If one believes Von Dolcke’s obituary, he hadn’t even arrived in the country until the late 1870s, so he could never have been Lincoln’s physician. The description of the cane makes it extremely doubtful that it actually ever belonged to Lincoln. The features on it are suspicious and it is most likely a fraud. Lincoln artifacts were highly sought after and many fake items were purchased by gullible collectors. “The cane is a straight, black ebony stick curiously carved and inlaid and was treasured by the president as a gift from a group of friends. Just below the handle behind thick glass is “Abe Lincoln” then a carved heart and “rail splitter.” next are nine square dots representing the nine states from which slavery was abolished. Beneath is a miniature carved log cabin, a likeness of Lincoln’s birth place” (Trenton Evening Times Dec. 13, 1929). It would be interesting to know where the cane is today!

In 1909, After being charged in Ohio for practicing without a license, Dr. Von Dolcke moved to Mt. Clemens, Michigan with his wife and three children. He died of an intestinal obstruction in Detroit on August 24, 1912. His death notice in a Detroit area paper was short, but expressed his continual claim of royal heritage. “Born in Iceland, the son of a Danish earl and connected with families of the bluest blood in Europe, Ludvig von Dolcke died in his home in Detroit after a short illness. He was 70 years old” (The Yale Expositor, Yale, St. Clair County, Michigan, 5 September 1912).

In 1909, After being charged in Ohio for practicing without a license, Dr. Von Dolcke moved to Mt. Clemens, Michigan with his wife and three children. He died of an intestinal obstruction in Detroit on August 24, 1912. His death notice in a Detroit area paper was short, but expressed his continual claim of royal heritage. “Born in Iceland, the son of a Danish earl and connected with families of the bluest blood in Europe, Ludvig von Dolcke died in his home in Detroit after a short illness. He was 70 years old” (The Yale Expositor, Yale, St. Clair County, Michigan, 5 September 1912).

Julie Schopieray is a regular contributor to Grand Traverse Journal.