November 11, 1896

Well after midnight Fire Chief Dupres, Alfred Waterbury, and Night Watchman Allen Grayson stood shivering in a brisk southwest wind that would ordinarily send them inside after a few minutes. Tonight, however, something seemed wrong: a dull yellow light flickered to the northeast of the Cass Street fire station where they had gathered. It danced on the thin crust of snow that covered the street in front of them, the same flicker they had all seen so many times before. Fire!

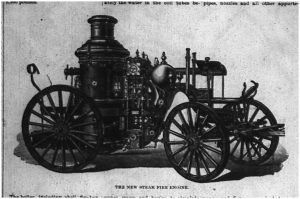

The alarm was sounded, a pealing of bells in a specific pattern that alerted firefighters to the location of the fire. It was in the direction of Front Street and Park, a place where frame buildings stood side-by-side, an invitation to a catastrophic spread of flames. Hitching the fire engine to the waiting team, firemen worked frantically to let the horse collars come down onto the horses’ necks; the rest of the harness was in order in less than four minutes.

Meanwhile, the fire within the steamer was turned up full blast to ready the engine for its pumping duties to come. As the men left the station upon their new engine, Queen City, the horses’ breath raising clouds of steam in the cold, they congratulated themselves on their quick exit. The steamer was new to the town, but they had practiced hard to get away fast, and that practice had paid off.

No more than two blocks from the station, they came to a stop in front of the Front Street House, a large wooden three-story hotel that dominated the south side of the street. Already flames and smoke billowed from the roof in places, the worst of it came from the part of the building that connected the large building on Front Street to the smaller frame building behind it by the alley. So quickly had the flames spread, the firemen doubted they could save the building.

Already persons could be seen scrambling out the windows on the first floor, most in their nightclothes. One brave soul hoisted himself out from a third floor window, making it somehow to the second story, and then dropping to the ground. A little girl, contracted into a ball in fear, rolled off the edge of a roof, only to be caught by a fireman. In all thirty people made it out of the fire: one did not. Ed Newberry, a Swedish hotel porter, was found later, his dog beside him.

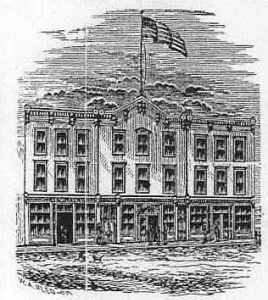

As predicted, the fire swept through the frame stores and saloons on the south side of the street, first the hotel, then a drug store within it, Broesch and Sons meat market, C.A. Cavis’s cigar store, Hiram Cook’s grocery, then a barbershop, and two saloons. Next, a large two-storied structure, the Rich & Hallberg building caught fire, one of its walls coming to rest against the brick Tonneller building. Four firemen were caught under the burning timbers, somehow escaping without serious burns. It was here the battle line would be set up to block the advance of the fire to the west. In the end, the line held.

One of the most gallant soldiers in the fight was the steamer Queen City, which performed magnificently, pouring water onto the flaming wall in a continuous stream, extinguishing the fire. It was backed up by the city’s water system. Unbelievably, nineteenth century hydrants and water mains performed without failure. Afterwards the newspaper would remark about the competence of the fire department and the water works in delivering water where it was most needed.

Even so, the blaze spread to the other side of Front Street. In what some described as a flaming arch reaching from one side of the street to the other, buildings on the north side began to catch fire. One by one they succumbed until they encountered Julius Steinberg’s brick opera house. Father Julius Steinberg and son Aleck as well as employees of the dry goods store attached played streams of water everywhere to cool the building. As cornices burst into flame, they hastened to put them out. In the end, though gravely damaged, the dry goods store and opera house were saved.

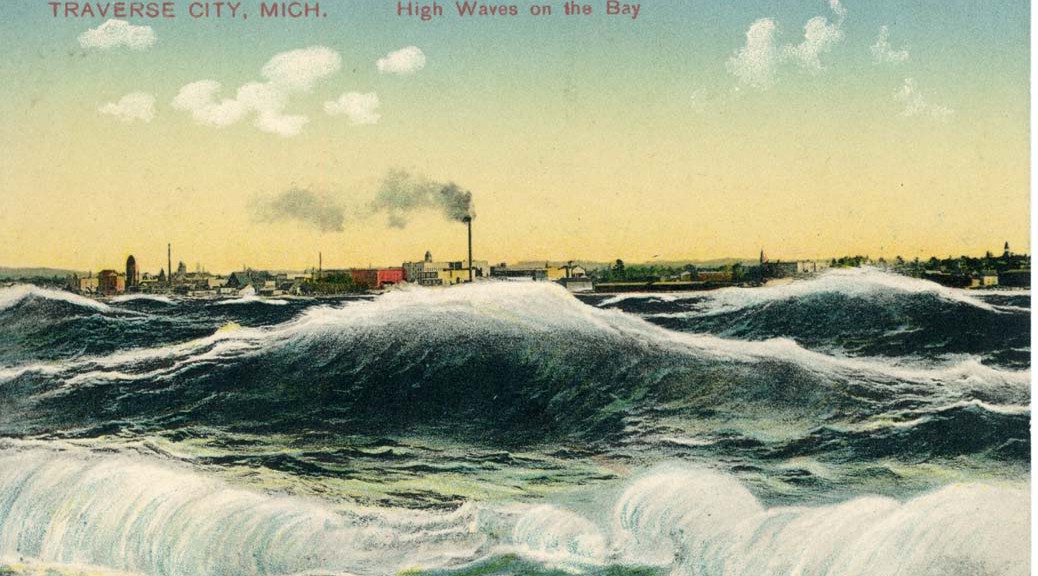

In fact, the city downtown was saved. Later, everyone remarked that the direction of the wind made all the difference, the fire starting at the Front Street House (or possibly the drugstore within), a location at the east end of the business district. The southwesterly gale-force winds drove the fire primarily to the east, keeping it away from the busy area of storefronts to the west. Credit also went to brave firemen, the fire engine that performed flawlessly, draymen who offered their services free of charge to those having to move store goods, the efforts of businessmen like Julius Steinberg, and ordinary citizens who did their part to help. One business owner, Mrs. E.M. Daniels, was singled out for her bravery in removing her grocery store stock and relocating it nearby at the peak of danger. Another citizen saw the glow of the fire from several miles away, and, suspecting the downtown was ablaze, drove to town just in time to save the merchandise in his sister’s store. There were heroes everywhere to be recognized.

Upon the rising of the sun the next day, the scene was horrific. Fourteen stores had been burned to the ground. More fortunate ones standing on the north side of the street suffered the ravages of smoke and heat, smudged with soot, with gaping holes where glass used to be in their front windows. Black charcoal, square nails lying on the ground, broken crockery, and a few other things resistant to the fire littered the ground. The Grand Traverse Herald remarked that it was the most serious fire that ever visited the city, and, indeed, it was.

November 6, 2016

Students of history sometimes receive unexpected rewards. For some time I had observed that the space across the street from Horizon Bookstore was being excavated to make way for a new building. Whenever the ground is torn up in the downtown area, you can count on interesting things being uncovered. Just two years ago, for example, West Front was repaved, that resurfacing job exposing Nelsonville, Ohio pavers, a brick that covered the road in years past. Now, seeing the earth in neat piles alongside the trenches, I had to go over and inspect the work.

I had something specific to look for. In 1896 I knew a great fire had leveled half a block of frame buildings on the south side of Front Street, the fire extending through the area where the digging was now taking place. Would there be any sign of the fire? Would there be charcoal buried down under?

The day is Sunday and all work had stopped on the excavation. A gentle wind fluttered the yellow ribbons warning passers-by to keep away, and enforcers of a “No Trespassing” sign were nowhere in evidence. In a quick yet fluid movement I ducked under the ribbons and stepped into the trench made by a shovel standing nearby. Nothing revealed itself at the surface, but a foot-and-a-half down there was a streak of black punctuating the beach sand that made up the soil. Bending down to pick some of it up, I sniffed at it and let out a small cry of joy: it was black charcoal from the fire.

It did not take long to find other things: broken window glass, two square, weathered nails, and bits of crockery, one of them big enough to read the name of the maker. Evidence of the fire was everywhere: How I wished I could sieve the pile of dirt to find more relics.

Picking up a piece of crockery, I felt a sense of connection to those living at these shores of Grand Traverse Bay at a time before automobiles, before radio, before television. Looking at the bottom of what could have been a bowl, I made out the maker: Meakin Ironware. A quick search revealed that the Meakin company, founded in England in 1851, had produced it more than 120 years ago. Somehow these ceramic shards survived the fire of 1896: people had handled this vessel, perhaps admired it, and then that awful thing happened. What they had lost now I had found. In a way that made me a participant in the event. History does that that to us: it weaves our own lives into the tapestry of the past.

Editor’s note: The Queen City fire engine described in the article may be seen at Fire Station Number 1 on Front Street.

Author’s note concerning this article: The description of the fire came from an extensive account in the Grand Traverse Herald. Reading the article carefully, a researcher can write a description like this:

Well after midnight, Fire Chief Dupres, Alfred Waterbury, and Night Watchman Allen Grayson stood shivering in a brisk southwest wind that would ordinarily send them inside after a few minutes. Tonight, however, something seemed wrong: a dull yellow light flickered to the northeast of the Cass Street fire station where they had gathered. It danced on the thin crust of snow that covered the street in front of them, the same flicker they had all seen so many times before. Fire!

Upon casual inspection it seems that the author has drifted perilously close to writing fiction: How could he know that three persons gathered in front of the fire station early in the morning? How could he know about the wind, its direction and speed? How could he know about the yellow light to the northeast that turned out to be the fire? The snow?

The answer is that the Herald account had references to all of those things. Far from creating an imaginary world, the writer only wove facts together in a manner that gave the scene life and interest. This kind of historical writing is frequently done nowadays. Seabiscuit, a tale of a famous racehorse, and Isaac’s Storm, the story of the Galveston hurricane of 1900, are just two examples that have become popular in recent years. The advantage of this approach is that it makes history come alive—often in contrast, to stodgy description in the traditional style.

From time to time the Journal will present stories told as an exciting narrative. Perhaps you would like to try your hand at it.