We will depart from tradition in this month’s Grand Traverse Journal by introducing a category of our publication soon to come: News from the Societies. As the old Grand Traverse Herald did, we will solicit news from outlying regions–Kingsley, Old Mission, Elk Rapids, and others–and print interesting tidbits here for all to see. If an organization wishes to announce coming events, ask for input from members, congratulate a member for outstanding work, or display photographs both historical and recent, the GTJ is the place to go!

Many of you know the History Center of Traverse City is at a crossroads in its own history. Below, readers will find a summary of that organization’s past changes and future plans. We hope publicizing this message from the HC will clarify its present situation as well as point to its future direction.

Updates & News at the History Center

Updates & News at the History Center

by Maddie Lundy, Executive Director

Programs and Events to look forward to:

Many things continue to change as a result of on-going conversations between the City of Traverse City and History Center of Traverse City. Departing from set ways of doing things, the coming year has several promising new events and programs for the community. Below is a brief overview of the latest news, discussions with the City, recent events, and plans for future History Center operations.

- Maddie Lundy (previously Maddie Buteyn, Acting Executive Director), has become the Executive Director of the History Center of Traverse City.

- The History Center has temporarily suspended public hours to focus on internal operations and preserve resources for the future of the History Center. The two part-time staff members, Laura Wilson and Peg Siciliano, have been laid off until funding improves. The HC looks forward to the time when these positions will be restored.

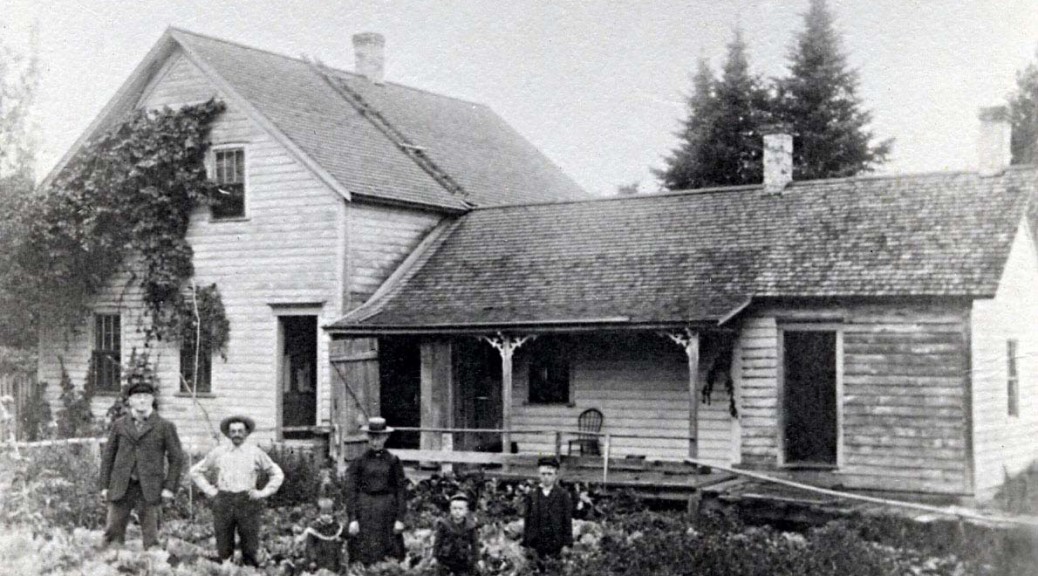

- A new plan of “taking history to the community” instead of “making the community come to history” is being implemented. We are developing new programming, collaborating with other groups interested in our history, displaying historical artifacts in new places, and telling the stories of our past off-site, in various venues throughout the community.

- History Center of Traverse City and the City of Traverse City are working on a possible new lease agreement; between the History Center and the recently merged Crooked Tree Art Center Petoskey & Art Center Traverse City, to share the Carnegie building.

- November brought an exciting fund-raising event produced by Maddie & Laura called ‘History Mystery Theater’. This “interactive murder mystery” was well received by all who attended. Performed at the City Opera House in collaboration with the Old Town Playhouse Aged to Perfection Players, the event came to life as a realization of a dream of Maddie’s several years ago. The story was custom-written by one of the ATP Players, telling about a fictitious murder that happened around historical figures during the Victorian era in Traverse City. We had a nice turn out, everybody saying how much fun it was and that we should do it again next year. What a wonderful way to connect with the community!

- Traverse City Megatherium Club: This is an exciting new program that will be held once a month at a local pub. We will have open dialogue on historical topics, enjoy a local drink and make new connections. Why call it the Megatherium Club? The name is based on a group of scientists that lived and studied at the Smithsonian during the nineteenth century. By day they would discuss serious scientific topics, but by night they would let loose to enjoy a bottle of ale, a relaxed conversation, and occasional high-jinks (like having sack races through the halls of the Smithsonian!). While our shenanigans probably will not include a sack race through the Smithsonian, we do look forward to attracting and meeting some new people who share a love for all things historical and for those quirky stories associated with such. Visit our website, http://traversehistory.org/ or our Facebook to find out more.

- Chautauqua in Miniature: During the early decades of the twentieth century, the Chautauqua came to northern Michigan, a smorgasbord of activities that included entertainment, musical and dance performances, and talks about engaging topics. On December 15th, 7:00pm at Horizon bookstore, local historian and author Richard Fidler will inaugurate the Chautauqua program with a discussion about racial, ethnic, and religious diversity in the Grand Traverse region, describing both the set-backs and advances in our progress towards understanding the various ways of being human. Future lectures will be held on the 3rd Monday of the month at 7pm at locations to be announced. We will feature guest speakers, interactive programs and open discussions. Visit our website, http://traversehistory.org/ or our Facebook to find out more information.

- Festival of Trains: This annual event featuring a myriad of model trains in a festive setting to delight all ages, will open at the History Center on Saturday December 13, 2014 and run through Saturday January 3, 2015. Festival Hours: Monday-Saturday 10a-6p, Sunday 12p-4p, closed December 25 and January 1. Holiday Hours apply on December 24 & December 31: 10a-2p and on closing day, January 3: 10a-4p. Admission: $5 (4 and under free), or purchase a Family Pass for only $25 (Unlimited access to the Festival of Trains, for 2 adults and up to 3 children–exceptions with approval of History Center Staff).

Please visit our Facebook page and traversehistory.org for more information. History Center of Traverse City is a nonprofit organization who owns a collection of over 30,000 photographic/paper records related to local history. We are the keepers of our past and ask for support in sharing and preserving this community’s rich history and culture! To become a member or donate please visit our website; traversehistory.org, email us at museum@traversehistory.org, or call 231-995-0313 ext. 106.