Monthly Archives: September 2015

The Artistry and Humor of Orson W. Peck (1875-1954)

Orson W. Peck (1875-1954), was a famed photographer and postcard maker of Traverse City. The video above looks at the thriving postcard industry of a hundred years ago as well as Peck’s unique contribution to it.

Grand Traverse Journal featured Mr. Peck and his work in a previous article.

Header image and the images within the video are courtesy of the History Center of Traverse City. Video is copyright Richard Fidler, 2008.

Storm Cripples Entire City–No Hope For Relief Until Night: Memorable Storms of Traverse City

There is nothing like weathering a storm to bring people together. After the storm of Sunday, August 2nd, how many complete strangers did you tell about the felled trees in your yard, or where you were standing when the hail started coming down? And, in return, how many of these stories did you listen to? Our “flashbulb memory” of the event may already be fading, but the repetition of sharing our common story certainly helps to hold that experience in our minds, in addition to the records kept in personal diaries and local newspapers.

As your friendly neighborhood reference librarian, I had more than my share of chances to hear the stories of narrow misses and total destruction. Each story led to the same question, “Do you think this was the worst storm on record?”

Already, you clever readers are parsing the question apart. What does it mean to be “the worst”? Are we measuring the number of people affected, or the dollar figure attached to the destruction? What type of storms are we comparing, just wind, or does snow and ice count? Who is doing the recording? While this article will attempt to answer some of these questions, unfortunately there are too many variables in the recording methods for weather, as well as in reporting damage by dollar amounts, to be able to provide a definitive answer.

A thorough look through the index of the Traverse City newspapers, available at the reference department at the TADL Woodmere Branch, and online thanks to Osterlin Library at Northwestern Michigan College, reveals that, indeed, weather phenomena has always captured our attention. Each article on “Storm Cripples Region,” and “Lightning and Hail Does Damage,” always make the front page. Of course, not only did freak storms provide the locals with something to gab about; many people’s livelihoods depended day-to-day on the land and seas. A true disaster could spell economic doom for the region; imagine if the crops were beaten down by hail, or an ice storm of any magnitude could prevent supply trains from making the trip up north and keep ships from docking.

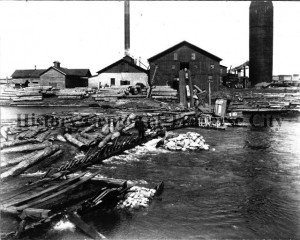

The following describes a severe windstorm (“with a velocity of fifty miles an hour”) of October 20, 1905, from the Traverse City Record-Eagle:

A storm which for severity has never been equaled in this region, struck this city early this morning of soon after midnight, though rain began falling at 5 o’clock yesterday afternoon which continued until at 2 o’clock this afternoon, a maximum of 1.4 inches had been registered at the government observatory by S.E. Wait. Coupled with the heavy rainfall, the heaviest this year, a wind which increased in velocity until it became almost a tornado drove the waters of Grand Traverse bay up with terrific bombardment along the entire waterfront scattering all water craft, with their sheltering houses, promiscuously along and shorewards until to stand and look at any portion of the bay it was no uncommon sight to see the wreckage of small boats pounding against the shore with logs, broken timbers, and thousand of smaller wreckage of the elements, these in themselves doing untold damage by the force of their combined pounding against docks, boat houses, railroads and embankments…

The article goes on to describe tattered awnings throughout the city, broken windows, damaged roofs, fallen trees, dismantled schooners; in short, a scene of devastation. Despite our recent history and the wind storm of 1905, it seems that snow and ice storms would have been feared to a great degree, if for no other reason than their frequency. Of the storms that made the news between 1865 and 1927, 9 were of snow or ice; 5 were floods; 3 (give or take) were general storms, sometimes with hail.

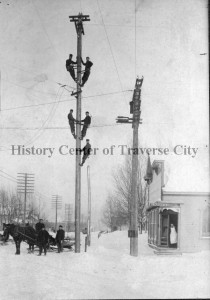

A deeper look reveals that, as our dependence on electricity and telephones increased, the reporting on snow and ice storms also increased. Perhaps there was indeed just more snow after the widespread placement of overhead lines, but we will leave that data for the next big snow storm. Whether it was a matter of more reporting, or more snow, this article from 1919 reveals the primary concerns were the immediate loss of power and the threat of people unknowingly handling live wires:

STORM CRIPPLES ENTIRE CITY

Snow and Sleet Work Havoc With Electric Light, Power And Telephone Wires.

Night of Total Darkness Followed By Great Haste To Repair Damage Today — No Hope For Relief Until Night.

Traverse City today is recovering from the most damaging storm in history. After a night of darkness and dread, business finds itself at a virtual standstill, with electrical current for power and lighting cut off, and telephone service demoralized.

The snow and sleet of yesterday was responsible. In the early day, heavily laden wires began to snap. By night, thousands of wires were down. For the most part, they were telephone wires, but in dropping on power wires, they disabled the latter, until, at six o’clock, conditions were so serious that both electric companies were ordered to completely disconnect their power… The fire department had its hands full yesterday afternoon and last night responding to fire alarms and taking care of fallen wires. Again people are cautioned to be careful around wires, and to handle no wires they find in the streets or alleys.

In the lightning and hail storm of September 16, 1920, The Citizens Telephone Company reported over 200 telephones out of work, and all toll lines (used exclusively for long-distance calls) out of commission; same with Bell Telephone. This report on the phone lines warranted a full paragraph of explanation, but agriculture was limited to one sentence at the tail end of the article. Reporting seemed disproportionate to the effect on citizens, as agricultural interests constituted the livelihood of many more people in the region than, say, the filing cabinet that lightning struck in the Johnson-Randall Company office, burning a hole through it.

In 1925, we see a shift back to reporting on agricultural interests, largely because of the high wind storm of June 10. The Traverse City Record-Eagle credits the hills surrounding the city proper as having saved the city from the brunt of the wind, “but south, west and east in the farming territory the gale was on a rampage and the wind was the worst in years.” The editors of the Record-Eagle claimed that it was impossible to estimate the actual extent of the injury to the corn crop, and could only report that “a survey this morning shows many fields of corn a complete loss”. In addition to those losses, many families also suffered from having farm buildings blown down and tops ripped off their automobiles, and a good number of “telegraph and telephone poles all over the state were toppled over.”

What have we gleaned from these reports of years past? That overtime, communications to the outside world began to take a precedence over immediate survival, as presumably the Grand Traverse Region could stand on its own without frequent supply trains. We can also guess that, in spite of this shift in attention, the disruptive nature of freak storms captured our interest in equal measure then as it does now.

Amy Barritt is co-editor of Grand Traverse Journal. Header image courtesy of Andy Simonds, “Wall Cloud- Lake Michigan,” taken 6 August 2008.

Famous Fly for Fishing calls Mayfield Home

Out in the little village of Mayfield, Grand Traverse County, is Mayfield Pond and the Halladay Family Memorial Park. An annual June celebration in Kingsley, just south of Mayfield, honors a particular event that took place at the Pond in the 1920s.

Do you know what happened at Mayfield Pond? Your hint: Leonard (Len) Halladay, and his good friend Judge Charles Adams, were both involved… Len was the local guide, and Adams a visiting enthusiast of a particular sport. He practiced his sport most frequently on the Boardman River and Arbutus Lake.

Thanks to reader Beth of Kingsley, we have our answer! One of the world’s most famous fly fishing ties was developed and tested right in our collective backyard on the Boardman River, the Adams Dry Fly. Len Halladay put little Mayfield on the map when he created the fly at the request of his friend Judge Adams, and the popularity of the fly has skyrocketed ever since. Some anglers say if they were only allowed one fly for the rest of their life, it would be the Adams.

Visit the Kingsley Branch Library for their display on the Adams Fly, and take a peek at an original tied by Halladay himself! History Road Trip!

“Cutting the Last Pine”: A Romantic Vision of the End of the Lumber Era, 1911

Scott Woodward (1853-1919) was a local author and publisher living in Traverse City at the turn of the last century. His work is firmly in the realm of realism, but it is often difficult to discern if his writings are autobiographical in nature, or if he’s just good at spinning a highly believable yarn. Woodward’s style is deftly described by George W. Kent, editor of Traverse City Daily Eagle circa 1910: “In his early life this author differed from his fellows in that his imagination was most vivid and he turned his visions, as some called them, into realities and wove them into his paintings of life in various phrases about him, taken from his peculiar viewpoint.”

The following is one entry in Woodward’s Life Pictures in Poetry and Prose, originally published in 1911, and tells the story of the felling of the last tree in a once-wide stand of pines. So romantic is the notion, that readers may be skeptical of his actual presence at the moment described, but the detail and memory cited gives one reason to believe his tale rings true.

“CUTTING THE LAST PINE.

The last pine- the lonely monarch in the midst of 2,000,000 feet of hardwood timber- is down. Its fall was one of the most pathetic sights I have ever had occasion to witness.

Through the courtesy of Frank Lahym, the lumberman, I found myself on a cold, frosty morning headed for camp. It was my good fortune to receive an invitation to be present at the cutting of the last pine to be found anywhere in the woods for miles around.

Great is the power of imagination, and before I was aware of it I was again among the scenes of thirty years ago.

THE SCENE CHANGES.

I was once more riding beneath the evergreens that hung low from the great load of snow they were supporting. In the distance I could here [sic] the steady “clip, clip” of the woodsman’s ax and the sharp ring of the saw, while away in the distance came the familiar warning, “Timber! Timber!” to all who might be in danger from the falling trees.

Again the scene changed with me and I stood beside the skidway and saw the great pines being loaded on sleighs with their 12-foot bunks. Log on top of log was being piled up on the sleighs until it looked like a veritable rollway for each team to take out.

The last log is rolled up into position, the familiar “chain over” is given and answered. The load is securely bound and then we start down the iced road to the river- I awake from my dream.

There is a jerk and a jolt and we find ourselves up-standing. One sleigh is fouled on the roots of a young sapling that some road monkey has unwittingly cut four inches too high.

Thus vanishes the dream of ’78 and with it the great rollway, the logging sleighs with their 12-foot bunks, the graded road which was kept in shape by the sprinkler over night, the overhanging trees that always had a weird and ghostlike appearance when clothed in their mantle of snow, and, last of all, the great banking ground where still flows the waters of the Manistee.

THE DINNER HORN CALLS.

We consign them all to the memories of thirty years ago, when I, too, was a unit in that great industry that will never return. We reach camp just as the great dinner horn is calling from labor to refreshments, and the lumber jacks come steaming in from their cutting of hardwood.

But it has changed, all changed. We sit down to a table loaded with roast beef, bread and butter, potatoes and coffee, capped out with pie and cookies. Ye gods, but what must one of our boys of ’78 have thought had he sat down to such a meal. However, we bolt it down while I think of the days when men sat around a fire in the woods and ate their beans and hard bread with good old “New Orleans” for dressing, and were satisfied. Had a man kicked on that he would have been hooted out of camp and compelled to take the hay road between two days.

In the midst of two million feet of hardwood in town 26 north of range 11 west stood one of the most beautiful cork pines that ever grew, three feet six on the sump, and where cut made five fourteen, one twelve and one sixteen-feet logs. When scaled by Doyle’s it measured a bit better than 3,000 feet. We had cut larger trees in ’78, as well as smaller ones, but none better. I counted the rings on the stump and came to the conclusion that this one pine had stood alone as a landmark, or sentinel, defying the storm and wind for better than 200 years, and had even escaped in days past the vandalism of the timber thieves.

I loved the pine, not for its intrinsic value alone, but for the memory it awakened. However, the time had come to cut and fell this last monarch. The hardwood was being cut around it. Huge piles of tops and brush were in every direction. It might survive until some future day in the hot summer, when some unthinking halfwit would drop a match in the dry tinder of the slashing. The prospect would be similar to that already seen in sections of Wexford, Roscommon, Kalkaska, Grand Traverse and many other counties.

After getting several good pictures of the landscape and the tree from various positions, I watched it being cut and skidded ready for the hauling.

Then, as the day was advancing, I was called to the sleigh for our return trip to the city. Strange it may seem. No one but an old lumberman can understand when I say I was both glad as well as sorry, to be present at the cutting of the last pine.”

Woodward, Scott. “Cutting of the Last Pine.” Life in Pictures in Prose and Verse. Traverse City: Scott Woodward, 1911. 133-136.

Amy Barritt is co-editor of Grand Traverse Journal. Beautiful pieces of prose and poetry reside unexplored in the rare books collection in the Nelson Room of Traverse Area District Library, and she invites you to come and find yourself a long-lost treasure.

The Dairy Lodge: An Architectural Relic from When?

This Traverse City landmark and staple of summer fun was recently recognized in a historical survey of Division Street (part of a Michigan Department of Transportation study), and has been proposed to be included on the National Register of Historic Places. What can you readers tell us about the structure? Any idea when it was constructed?

This Traverse City landmark and staple of summer fun was recently recognized in a historical survey of Division Street (part of a Michigan Department of Transportation study), and has been proposed to be included on the National Register of Historic Places. What can you readers tell us about the structure? Any idea when it was constructed?

A Tribute to Floyd Milton Webster, 1920-2015

We at Grand Traverse Journal mourn the loss of our fount of knowledge and kindred spirit, Floyd Milton Webster, the historian and elder of the Village of Kingsley. At the ripe age of 95 he departed this earthly realm, on August 15, 2015, at his home on Fenton Street. We could not have wished more for him, than to pass on in the home he loved, to join his beloved wife Melvina.

Floyd will be remembered for his charm with the ladies, his quick wit, and the merriment he always left in his wake. He was born on June 21, 1920 in Alma, the son of Walter and Martha (Vassar) Webster. Please read an earlier article published in GTJ for more on Floyd’s courtship and marriage in the spring of 1943, as well as his overseas service in World War II, in his own words.

Floyd will be remembered for his charm with the ladies, his quick wit, and the merriment he always left in his wake. He was born on June 21, 1920 in Alma, the son of Walter and Martha (Vassar) Webster. Please read an earlier article published in GTJ for more on Floyd’s courtship and marriage in the spring of 1943, as well as his overseas service in World War II, in his own words.

Floyd will be especially missed by longtime friends Peter and Connie Newell, regular contributors to GTJ. Thanks to the Newells, we now have Floyd’s remembrances to hold for posterity, as well as the following poem, written by Connie and read aloud by Peter at Floyd’s memorial service on August 19th at the Covell Funeral Home in Kingsley. Connie graciously allowed the publication of this work, for which we are indebted, as this is the fitting tribute our dear friend deserves.

The Village Elder

By Connie Newell

May, 2009The “older” man who walks and drives

Is one who visits all

He sees on his daily travels,

And they wait for him….With quick wit, flashing blue eyes

That twinkle before a ready joke,

He makes us laugh

Because “It makes IT better.”And our lives get

A whole lot better

Even for a moment

And sometimes, that moment is…All that we need

To regain our inner balance

To be able to get through

Another mundane day.This man, Floyd Webster, has lived here

For so many years that most

Of us have no idea how many.

Because, to us, he has been here forever.It’s not that we take his daily rounds,

His jokes, his sweetness,

For granted

It’s just that he is Floyd,And he’ll always be here

Even if he goes to be with his wife

Who left such a long time ago

That few of us remember her.And Someone else moves into

His perfect little white house

On Fenton Street

As clean as a whistleWith the flag blowing briskly

In the wind

And always two chairs outside

One for me and one for him.He’s not young, you know,

Only in his heart

Where it counts, and

Let’s face it ladies, he’s very datable.People talk about Floyd.

They say all kinds of things

Which are always good and

The community, sometimes gets scared.“I saw Floyd today, and I

Didn’t think he looked

All that good.

Do you think he’s OK?”Everyone watches out for Floyd,

Everyone cares.

Everyone Loves him

Because he IS the town.He knows everything there is

To know about it

And can tell you

If you can spare a day or two.Which is why it’s good that

We have a new library

So most of the stuff he’s collected

Has a good home.He deserves that

Because he’s a rascal and

Rascals are hard to find

Because it takes a good man to be one.Many eyes see him almost every day

As he buys his lottery ticket,

Though he’s already worth a million

Telling a joke or just being thereBecause he makes us feel

Better about ourselves,

We hope that we can

Show that his energy was well spent.We want him to know how

Much he is loved by this Village

And we are very grateful

That he has never leftHis niche completes

Our Kingsley story.

Nope, he has hung out here for too

Long to ever say good-bye.He knows where all the bodies are buried.

Maybe he’ll tell,

Wouldn’t that be great! I hope he does

Before he forgets where he isAnd wakes up

With his beautiful wife

And they both stroll, hand in hand

And we are all unaware.

Don’t Kill ‘Em: Nuptial Flights of Ants

The voice on the other end was animated: “Come over now! They’ve got wings and they are swarming!”

I knew what she was talking about because I had discussed the subject previously. Ants were beginning their nuptial flights.

“I’ll be right over! See what you can do to keep them from flying!” I answered with unrestrained emotion.

“A spoonful of sugar? A dead beetle carcass? I don’t know what to do!” she wailed, enjoying the conversational gambit. I took no time to reply and jumped into the car with my camera.

My friend met me in her driveway when I arrived and led me to the scene. There they were: tens of small winged forms with two or three larger winged ones mingled among them. Some tiny workers, wingless bit players in the drama, milled around as if uncertain what to do.

My camera is not the best and my skills as a photographer are unremarkable, but I set it on macro, focused, and shot five times without a flash. The best ones appear in this account.

The word “nuptial” has to do with marriage, but that term has to be stretched to encompass the nuptial flights of ants. Males—the drones—finally emerge from the depths after having been taken care of the entire season long. No doubt some female humans can relate to that scenario. At the same time, a number of virgin queens were similarly readied for this day, the day they would be inseminated and fly off to found a new colony. It is a “marriage” in name only.

When the day length is right—late summer as a rule—and when conditions of humidity and sunlight somehow satisfy senses of the colony, the nuptial flight begins.

One-by-one the females depart, the males flying up with them. No doubt a chemical exuded by them induce the males to fly upwards, towards the light. However, the drones do not necessarily inseminate the colony’s virgin queens: after all, that would be incest since all members of the colony have the same DNA. Under the best scenario, males from another colony would mate with them far away from the home colony.

The mating of ants takes place quickly and without ceremony. After separating, the “lucky” male flies away to die as his food reserves run out. He has served his purpose, and no longer receives the attention of his colony.

Meanwhile, the queen continues her flight, carrying the sperm in an internal packet which she will use over her entire reproductive life (several years to as many as 23). If she avoids interactions with predacious insects, birds, and car windshields, she will settle down and remove her wings through a deft motion of her body. Then she will seek to dig a burrow and lay her first eggs. It is the only “manual labor” she will have to perform because newly hatched workers will take over the mundane tasks of gathering food, carrying out the garbage, and taking care of new workers as well as the new princes and princesses of the next generation.

By the way, the new potential queens differ not at all from the workers: they only receive special food that grants them royalty. In a sense, it is like the transformation of a frog into a prince, since in each case a lowly, unprepossessing creature becomes something wonderful. Males, on the other hand, differ significantly from females: they have only one set of chromosomes (as opposed to two sets in the females). No doubt they, like human males with only one X chromosome, suffer certain genetic diseases more frequently than the females that surround them.

Winged ants cause psychological trauma in some persons. They grab insecticides and spray until the ground is littered with insect carcasses. I don’t know if this account of ant reproduction will score any points with those who regard the only good insect as a dead insect, but I hope it might suggest that the winged forms are temporary and cause no harm. They do not eat our food, nor do they sting or bite.

It is not too late to see winged ants. In their book Journey to the Ants, E.O. Wilson and Bert Holldobler describe the scene of a common ant that enacts nuptial flights during September:

The slaughter of failed reproductive hopefuls can be seen all over the eastern United States at the end of each summer, when the “Labor Day ant,” Lasius neoniger, attempts colony reproduction. The species is one of the dominant insects of city sidewalks and lawns, open fields, golf courses, and country roadsides. The dumpy little brown workers build inconspicuous crater mounds, piles of excavated soil that encircle the entrance holes, causing the nests to look a bit like miniature volcanic calderas. Emerging from the nests, the workers forage over the ground, in among the grass tussocks, and up onto low grasses and shrubs in search of dead insects and nectar. For a few hours each year, however, this routine is abandoned and activity around the anthills changes drastically. In the last few days of August or the first two weeks of September—around Labor Day—at five o’clock on a sunny afternoon, if rain has recently fallen and if the air is still and warm and humid, vast swarms of virgin queens and males emerge from Lasius neoniger nests and fly upward. For an hour or two the air is filled with the winged ants, meeting and copulating while still aloft. Many end up splattered on windshields. Birds, dragonflies, robber flies, and other airborne predators also scythe through the airborne ranks. Some individuals stray far out over lakes, doomed to alight on water and drown. As twilight approaches the orgy ends, and the last of the survivors flutter to the ground. The queens scrape off their wings and search for a place to dig their earthen nest. Few will get far on this final journey…

Most winged forms die without our help. Insecticides are superfluous. Besides, why would anyone want to do away with a major natural spectacle?