By Robert D. Wilhelm

Edited by Julie Schopieray and Richard Fidler

[Editors note: This is a transcription of a manuscript Bob Wilhelm wrote over a long period of time, with updates ending in 1986. Some spelling and punctuation has been changed, and transcriber’s notes for clarity are in brackets]

A Note by historian Al Barnes

Doing the Impossible

I would have said it couldn’t be done. When Bob Wilhelm told me that he was going to do the history of the Wilhelm family of Traverse City I gave encouragement. However, tracing the family from their roots in Bohemia, before the turn of the century, to the “new world” and thence onward in time to the present day, was a task for a research group and not for one person.

From time to time he contacted me and we discussed many problems. Months turned into years and he persisted. He discovered the power of determination born in the pioneer family. He reflected this determination as page after page of the story unfolded.

Completed, the manuscript is fascinating and inspiring. I am positive that no stone was left unturned and no name left out of the story if that name left an echo at any point in the story of the Wilhelm family. I would not have had the patience.

CHAPTER 1: Conflagration in Bohemia

Central Europe in the mid-1800s was in turmoil. Count Clemens von Metternich, alter ego of the emperor of Austria and the Hapsburg dynasty, was not willing to let the demands for reforms sweeping through Europe spread into the Austrian Empire.

There were several reasons leading to the wave of dissatisfaction. Because of the Industrial Revolution, massive numbers of country people flocked to the cities hoping to improve their living conditions. Disillusionment soon swept through the masses. Unemployment, unequal distribution of wealth, slums, and unhappiness with an absolute monarch led to widespread disorders.

The government moved with brutal efficiency to quell the rising unrest. The military and the secret police were used to stamp out opposition. To keep the military ranks full, all young men were required to serve seven years at virtually no pay. The future held little more than becoming “cannon fodder.”

The Hapsburgs in their many wars with other European monarchs, needed young men. Country peasant stock was in the front lines. The attitude was “Why waste your best trained soldiers?”

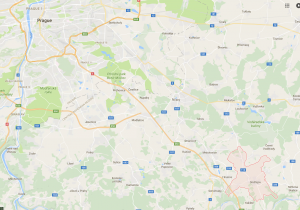

In Bohemia, during the 1848-1850 period, the pan Slavic desire for Slavic unity and independence was proclaimed by Bohemian leadership. Meetings for unity and independence were held in Prague, but the speeches by the leaders resulted in confusion due to different languages.

Riots broke out in Prague and the Princess Windisch Gratz, wife of the governor, was killed by a stray bullet.

The Austrian cannons destroyed the patriotic hopes by the bombarding of Prague. The Bohemians were not able to withstand the armies of the Hapsburg monarchy. The bombardment was the beginning of the end for the independence movement. The Austrian army remained faithful, and a new period of desperation descended. It was so harsh that it made many yearn for the unhappy days under Metternich.

CHAPTER 2: Ondrejov to “Cincinnati”

It was during the summer of 1853 that a pamphlet describing the wonders of Cincinnati, Ohio, was circulated by a land agent in the village of Ondrejov, Bohemia.

Eva Wilhelm could not resist glowing reports of the mysterious land across the ocean. She started talking and tried to persuade her husband Joseph, a prosperous shopkeeper, to make the journey. Her pleading was rejected, but her brother-in-law and his wife, John and Mary Wilhelm, who lived in the nearby village of Cerna Buda, decided to go to America.

John Wilhelm was a tailor, but at the time he was dyeing and printing cotton fabrics. He was making a comfortable living for his family, but the future of his occupation was bleak. The talk of the area was Cincinnati, Ohio and its opportunities. While others could not make up their minds, John sold his interests and the family left on October 23, 1853. They reached New York in December.

Mary and two of their four sons were ill when they landed. They were admitted to the Marine Hospital in New York where one of them, Frank, died the next day. The second ailing son, Anton, died about a year later. The other children, Emanuel (age 13) and John (7 1/2) were temporarily placed in a children’s home until their father could get a job, their mother would be released from the hospital, and a boarding place could be found.

Braiding on garments was fashionable at the time. Being skilled in the art and able to speak German in addition to Bohemian, John was hired by a German tailor. When his wife recovered from her illness, the tailor offered her a job. John was curious about how the tailor knew she was a seamstress. The tailor explained he had noticed the neat patches on his shirt.

Emanuel, son of John and Mary, began working in a map making business during the day and attended school at night learning English.

CHAPTER 3: Mass exodus: Ondrejov to New York

Despite word of tragedy and hardships in New York, Eva Wilhelm was constantly urging her family and friends to leave Ondrejov. By the fall of 1854 her persuasiveness overcame the apprehensions. The exodus began.

Joseph Wilhelm and his wife Eva; his brother Anton, Joseph Kyselka, Wencil Bartak, Albert Novotny, Frank Kratochvil, Frank Lada, Joseph Knizek and Frank Pohoral, all with their wives and children, the mother of Joseph and Anton Wilhelm, and Pohoral’s unmarried sister were part of a group that finally settled in the Grand Traverse region.

Not all of the larger group settled in Michigan. Some migrated to Wisconsin. A cousin of Frank Kratochvil began the settlement of New Bohemia on Long Island, New York.

Even though Cincinnati was originally on the minds of the hundred migrants, not one settled there.

Unlike so many of the central Europeans who were totally destitute, this group, though lacking wealth, was nowhere close to being paupers. All of these families had the necessities of life even under the adverse conditions affecting Bohemia. They all had common school education. Anton Wilhelm’s wife Jennie was a teacher. She insisted that her family speak English, the language of their adopted land. Even though her children could speak Bohemian in later life, they were one of the few who could speak English without an accent. The men had all learned a trade while the women were all skilled in some form of needlework.

It was a three day journey from Ondrejov to the German seaport city of Bremen. A week’s search to find a sailing vessel resulted in the group boarding the Herzogen Von Alderberg.

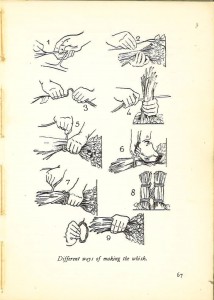

There were steam vessels available for the journey, but a letter from John Wilhelm warned about the dangers of the steamers because one had blown up in the New York area. The boat carried 120 passengers, mostly Czechs (Bohemians), including a Czech band whose music helped break the tedium of the long journey There were also eighteen unmarried Germans and an English family named Williams on the consist. Each of the families was expected to furnish his own bedding, and their ticks (a cloth case for a mattress or pillow was rather coarse flax grown on the farms, spun by the women and woven by the town weaver).

One of the Czechs had a feather bed, part of a bride’s dowry, made of goose feathers. This was stolen and resulted in great discomfort in the winter weather. In addition to the warmth provided, these feather beds could be used as collateral for a loan.

The first meal served aboard was smoked, salty fish. Because the supply of water was limited, the passengers suffered greatly. Seasickness was another frequent misery. Some of the passengers brought dried fruits, mainly pears and prunes. Ondrejov had a community drying house where they could bring their crops for a small fee.

The voyage lasted longer than scheduled, seven-and-a-half weeks. Food and water supplies ran low. A.J Wilhelm in later years recalled that the basic diet at the end of the journey was black bread.

Because of the suffering of the children, Frank Lada lowered a small container attached to a cord into the diminishing water supply to relieve the distress. If a crew member should have observed such a happening, Lada would have been punished for breaking the ship’s rules.

When the boat finally arrived in New York, a number of children had to be admitted to an immigrants hospital for treatment. Many were emaciated from the lack of proper food and other discomforts suffered on the voyage. Many children died soon after arrival at the hospital and many other sick children lived a little longer. The large hospital ward was filled with rows of cots occupied by sick children.

Mothers were not allowed to be with their children in the hospital. Elizabeth Bartak’s mother pleaded with the nurses, but her requests were denied. She offered to scrub floors, a nurse tiring of the pleading pointed to a large dog and threatened her with attack. One day she arrived with patterns of lace. Going through the motions of knitting, the nurse understood she would make her some if she was allowed to stay. The offer was accepted.

A constant terror faced by the unsuspecting and trusting immigrants was the confidence men who preyed on all the newly arrived at the dock. As the Herzogen Von Alderberg tied up at the New York dock these people were only too helpful. Speaking their native language, a stranger offered to take them to a clean, moderately priced hotel, They trustingly and gratefully accepted. When the immigrants were presented with the bill, they realized they had been fleeced. A fist fight erupted. The hotelkeeper and his accomplices locked all the doors and the men were not to be released until they had given up all their worldly belongings. Fortunately, through the efforts of John Wilhelm and some of his friends he had made during his year in the United States, the situation was brought to the attention of the authorities and a refund of the overcharge was ordered. The court also ordered that these dishonest practices should cease. This satisfactory ending was rare. Most of the immigrants who were fleeced lost everything. Warning letters from the newly arrived to their family and friends back in Bohemia spread through the communities.

The carrying of money was especially dangerous. Unscrupulous passengers and crew members on the boats robbed the helpless. People waiting at the dock wanting to “help” the newly arrived disappeared as soon as they gained their worldly possessions.

Anna (Dufek) Brown was determined to make the journey to Leelanau County, Michigan. Her father, fearing the worst, wouldn’t allow his daughter to carry any money. All of her possessions were placed in a homemade trunk. Most of the space was for her featherbed. She wore a paisley shawl around her shoulders for warmth. She was presented with an amethyst or garnet necklace which was to be traded in for money when she reached New York. Arriving in New York, the immigrant agent ripped the necklace from her neck and put it in his pocket. His only comment was that people didn’t wear such necklaces in America.

The shopkeepers in New York used small coins to make change. Many could not get used to the American money and were easily confused. Another tactic of the unscrupulous was to give a handful of small change. The floors would be covered with sawdust so it would be difficult to recover your money. (This spreading of sawdust was done in the Grand Traverse region during the lumber era by some of the bar owners. Presumably drinkers would have a hard time finding change that had dropped to the floor).

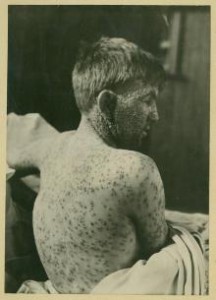

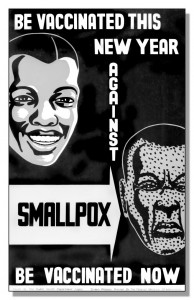

Despite the problems of “strength makes right” hundreds of Bohemians from the area around Prague made the journey. Disease brought tragedy to many. Loss of all worldly goods by many slowed down the new life opportunities temporarily.

The exodus to the Great Lakes area was in full flight.

Look forward to the continuation of the History of the Wilhelm Family by Robert D. Wilhelm in upcoming issues of Grand Traverse Journal.