The following vignette was provided by the author of Murder on Old Mission, Stephen Lewis. Lewis is currently crafting the sequel to that well-received novel. Expected publication is early 2016. Murder on Old Mission is currently available at local booksellers and at Amazon.com.

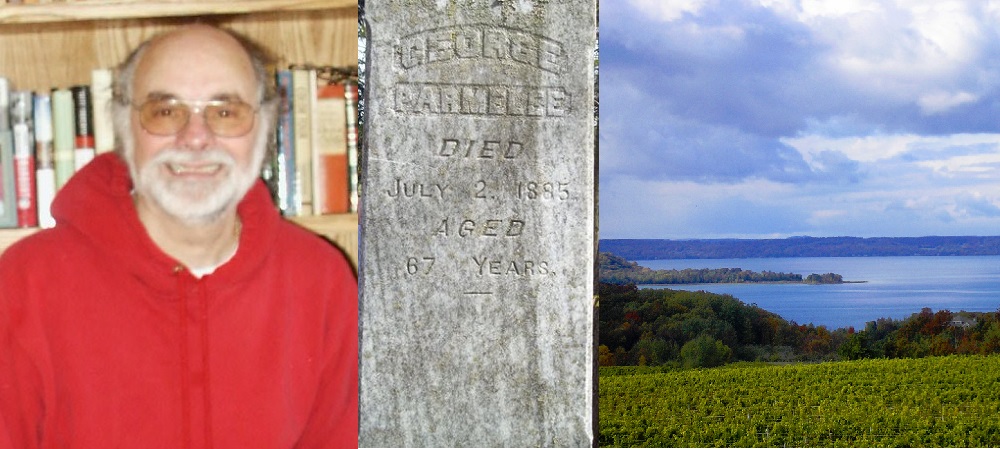

In 1895, Woodruff Parmelee, the scion of a major Old Mission Peninsula farming family, was sentenced to life imprisonment in solitary confinement for the murder of Julia Curtis, his pregnant girlfriend. Julia’s body was found at the base of Old Mission Peninsula in an area near East Bay that was called the hemlock swamp. By modern standards, the prosecution’s case against Woodruff was well short of solid. It depended upon the questionable forensic evidence of footprints found near the body, which may or may not have been Woodruff’s, but could equally well have been those of any of the thirty or forty men who were searching for her. There was also the eyewitness testimony of a hired hand named Stagg who had a history of perjury and who offered to leave the area if he were paid enough.

Parmelee’s defense was built on an alibi. He could not have killed Julia, he claimed, because at the very time she went missing, he was working on a new road on the other side of the Peninsula heading toward West Bay. The prosecutor’s witness testified that he had seen Parmelee heading east, away from that new road. Parmelee said, no, he was going the other way. Clearly this difference is crucial. If Parmelee could prove his version, it would establish his alibi, and he would have to be acquitted. He could not be in two places at the same time.

Receiving scant attention in the detailed newspaper reports of the trial was the testimony of Parmelee’s son Louis who supported his father’s alibi. He stated that when he went to join his father working on the road, he met his father coming from the west.

The testimony of both witnesses was less than convincing: Stagg’s character is at issue as is Louis’s assumed filial attachment to his father. If we say that their testimony cancelled each other out, not much besides the footprint evidence remains of the prosecutor’s case. Nonetheless, Parmelee was convicted. In all probability, the unstated basis for his conviction was his troubled marital history, including two failed marriages, and the fact that he was twice the age of Julia.

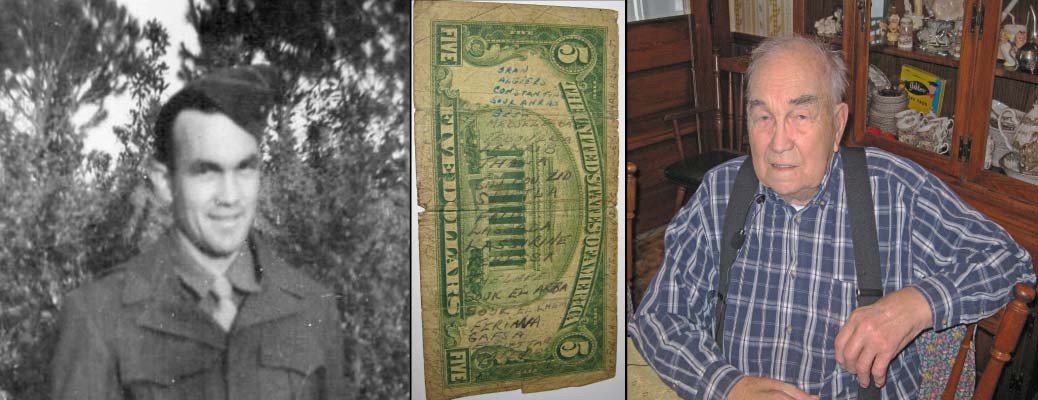

This is the story I fictionalize in Murder On Old Mission. In my version, I focus fully on the testimony of the son. By changing some facts and adding others, I intensify the son’s situation. That book’s penultimate chapter takes the story to Parmelee’s conviction. Its very last chapter provides the bridge to the sequel I am now writing. That chapter jumps twenty years ahead when Parmelee, in spite of his sentence, is again a free man, returning to Traverse City where he is reunited with his son.

My sequel intends to fill in what happened between conviction and release. Parmelee was convicted of a most heinous crime. His sentence reflected the severity of the community’s judgment. If capital punishment had been available, Parmelee would have been a candidate for execution. Yet, not only did he not serve his life sentence, he was released, and in fact lived another twenty-seven years, almost outliving Louis, who died shortly after him.

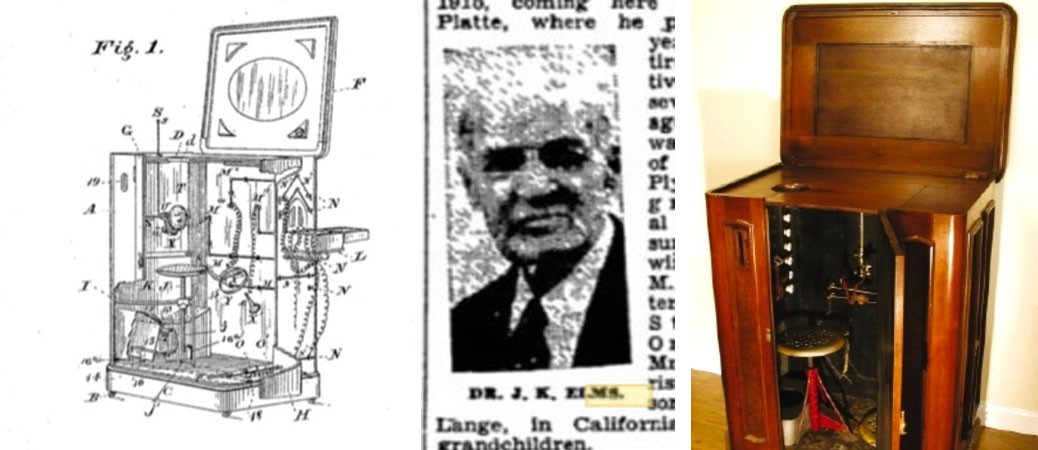

There is one salient fact that explains Parmelee’s release: the intervention of Governor Woodbridge Ferris, who interviewed Parmelee in Jackson State Prison immediately prior to Parmelee being paroled. My research as to why this extraordinary intervention occurred has come up empty. Why the governor should have picked Parmelee out of all the prisoners in Jackson at that time for his personal assistance remains a mystery.

And that provides me the opportunity of creating fictional circumstances to fill that void. As I did in Murder On Old Mission, I am building on the historical facts, but this time, as well, I am constrained by the fictional facts I created in the first book.

That is an interesting challenge.

Review of Murder on Old Mission

Amy Barritt, co-editor of Grand Traverse Journal

Reminiscent of Arthur Miller’s work, The Crucible, Murder on Old Mission is a fictionalized account of a true crime that took place on Old Mission Peninsula. Although we modern readers might associate the Peninsula with breathtaking views and wineries, author Stephen Lewis deftly realizes the relative isolation of that region in the late 19th century, which would, on occasion, encourage intense interpersonal relationships to compensate. Readers are invited to see both sides of that coin, in the passionate relations between Sam Logan and Margaret Cutter and in the unexpectedly adversarial relationship between Sam and his son, Isaiah.

Highly descriptive and full of rich conversations, this is the type of book wherein the scene can play out in your imagination as a movie would. A drama of the highest order, and well worth a sequel, which I eagerly anticipate.

Excerpt from the sequel to Murder on Old Mission

by Stephen Lewis

Isaiah adjusted his sailor’s gait to the flat surface of the road leading to the church. Everything else was eerily familiar. It had been five years since he walked up this road on the day that began to change his life. But the road itself, inanimate and without memory, just lay insensate beneath his shoes. Somehow he had thought that the dust rising beneath his feet would carry with it echoes of that day, perhaps a word, a sigh forced out between clenched teeth, an image of a face drawn in pain, a tear trickling down a man’s unshaven cheek or finding a path along the worn furrows of a woman’s face, and above all a pervasive black of mourning.

On this morning to be sure, the shadow of death argued against the bright rays of the sun this late spring day. But this time, death’s face wore a bemused grin, a weary acknowledgement that the deceased had simply run his appointed course and it was time for him to be gathered into the ground. In that respect, this occasion could not have been more different than that one five years ago when a person in full bloom had been cut down.

The handle of the church door felt the same as it did that day when he had grasped it with a hand warm and wet from sweat, his lungs gasping for air. And the hinges squeaked just as they did then. On that day, when he pushed the door open ever so slowly to minimize the disturbance of the squeaking hinges, he was confronted by an empty building. He was too late. Through the rear door, he could see the mourners gathered around the freshly dug grave into which the woman he loved would be interred, and standing, ashen faced, among the mourners was his father soon to be convicted of putting her there.

Today, however, the congregants were all in their seats. He stood for a moment at the rear of the church. He expected heads to turn around to gaze at him in response to the loud squeaking of the door on its hinges but none had. He had tried to prepare himself for that eventuality, but had not come up with a suitable response. Several people did now, belatedly, turn in his direction, but then swiveled their heads back toward the front of the building. Perhaps, he figured, they had not recognized him. It had been, after all, some years.

Biography of the Author

Born and raised in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn, Stephen Lewis holds a doctorate in American Literature from New York University, and he is Professor of English Emeritus at Suffolk Community College, on Long Island, New York. He now lives with his wife on five acres in a restored farmhouse on Old Mission Peninsula in northern lower Michigan.

After having written The Monkey Rope (1990), and And Baby Makes None (1991) two mysteries set in Brooklyn and published by Walker & Company, Lewis turned his attention to a different time and place, New England in the seventeenth century, for Mysteries of Colonial Times. The stories set in Brooklyn dipped into Lewis’s childhood, while this second series, written for Berkley, drew upon his expertise as a scholar of New England Puritanism. The Dumb Shall Sing, the first of this series was published August, 1999, followed by The Blind in Darkness in May, 2000, and The Sea Hath Spoken January, 2001. Murder On Old Mission, put out in 2005 by Arbutus Press, was a finalist in the historical fiction category of ForeWord Magazine’s book of the year awards. His mystery novel, Stone Cold Dead, was submitted by Arbutus to the 2007 Edgars. Belgrave House recently published A Suspicion of Witchcraft, his first ebook original novel.

Before turning to mystery fiction, Lewis published short stories, poetry, scholarly articles, and five college textbooks, including Philosophy: An Introduction Through Literature (with Lowell Kleiman, Paragon House, 1992) which is still being used in a number of colleges. This past December, Broadview Press, a Canadian independent, published Templates, a sentence level rhetoric that relates syntax to computer templates.

He continues working in various fiction genres. His more recent short story publications include “The Visit,” a literary short story in The Chariton Review, “Eagles Rising,” a mystery story in Palo Alto Review, “A Foolish Son,” a historical story published online in the Copperfield Review, and “The King Knew Her Not,” in Green Hills Literary Lantern.